© Università degli Studi di Padova - Credits: HCE Web agency

- HUMAN RIGHTS CENTRE

- RESEARCH AND COURSES

- Publications

- Archive "Peace Human Rights"

- HUMAN RIGHTS CENTRE

- RESEARCH AND COURSES

- Publications

- Archive "Peace Human Rights"

Sofia Antonelli, holds a master’s degree in Human Rights and Multi-level Governance from the University of Padova. She recently got another master’s degree in Prison Law and Constitution from the University of Roma Tre. She is currently a Civil Service Volunteer at the Ministry of Justice’s Probation Office in Rome. This In Focus article is excerpt from her master thesis, discussed in November 2018, under the supervision of Prof. Paolo De Stefani.

----------------------

Since the mid 1970s, the growing concern about the widespread use of torture and ill-treatments throughout the world led to the creation of specific legal instruments dedicated to prohibit and condemn such abuses. At the international level, in 1984 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT), entered into force on 26 June 1987 following the twentieth ratification. The UNCAT introduced three main innovations. In short, it provided for an internationally agreed legal definition of torture; it urged Member States to include the crime of torture within their legal systems; and it established the Committee against Torture (CAT) as its monitoring body, in charge of supervising the Convention’s implementation mainly through the exam of periodic reports submitted by States Parties. Despite the relevant changes brought by the Convention, according to several experts in the field of deprivation of liberty the system designed by the United Nations was not enough to significantly contrast the use of torture.

Even before the Convention’s adoption, some international organisations began to think about the necessity of a more effective system, working to prevent, instead of reacting to, the use of torture.

The idea of such a system made its first appearance in an article called “A new weapon against torture”, published in Geneva in October 1976 by the weekly journal “La Vie Protestante”. The author of the article was the Swiss banker and philanthropist Jean Jacques Gautier, founder of the Association for the Prevention of Torture (APT).

Inspired by the International Committee of the Red Cross’ monitoring activities of prisoners of war camps, the so called “Gautier Proposal” urged the adoption of a new international system of periodic and unannounced visits conducted by independent experts to any place of deprivation of liberty. According to Gautier, only by opening the doors of places of detention to external eyes, violations and abuses could be strongly defeated.

In line with this new approach, besides judicial measures aimed at reacting to violations once they have already occurred, torture and ill-treatments’ cases need strong proactive actions. There is evidence that people deprived of freedom tend not to report the violence experienced to the competent authorities because of fear of retaliation, poor information or due to the lack of adequate legal assistance. A constant monitoring activity able to identify the dysfunctional elements and the possible causes of ill-treatments is thereby essential in order to prevent abuses from happening in the first place and, if so, to avoid their reiteration. Furthermore, the very existence of preventive mechanisms is per se able to ensure an effective action against torture: the awareness of eventual unannounced inspections is by itself a strong deterrence to perpetrate violence.

In 1987, one year after Gautier’s death, his proposal was finally realized at the regional level by the Council of Europe. In the attempt to strengthen the legal prohibition of torture enshrined in Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the Council of Europe decided to establish the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT).

The creation of the CPT was a real revolution in the struggle against torture. For the first time, States decided to open their places of detention to outside eyes, enabling foreign commissioners to visit “any place [within Member States’ jurisdiction] where persons are deprived of their liberty by a public authority” (Art. 2 European Convention for the Prevention of Torture - ECPT). The CPT was designed as an innovative non-judicial mechanism equipped with unique tasks, unprecedented in the history of international and regional organisations. Indeed, it is the first organism provided with a preventive and proactive function in the field of human rights.

Without any risk of overlapping, the proactive action of the CPT complements the reactive one of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Both fighting against human rights violations, the two organisms operate at different times, one intervening in order to prevent violations from happening while the other reacting if violations have already occurred.

The establishment of a European monitoring mechanism had a strong impact on the creation of a similar system at the international level, giving more precise indications on how to design it and on its actual work.

It began, in this way, the long and complex negotiation process that will end, after several delays, ten years later with the adoption of the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (OPCAT) by the General Assembly in December 2002.

The OPCAT established an extensive system of periodic visits undertaken in any place of deprivation of liberty by independent organisms provided with broad inspection and recommendatory powers. The OPCAT system is, at its core, composed of the Subcommittee for the Prevention of Torture (SPT), an international organism made up of independent experts, and at the domestic level of a National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) for each Member State.

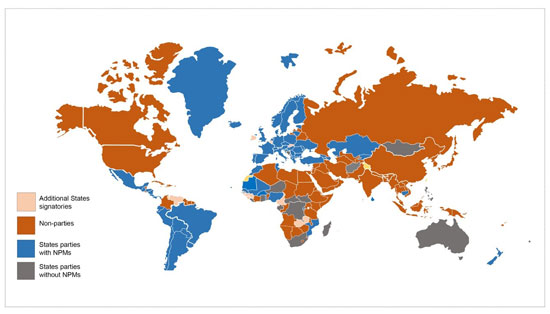

A single monitoring mechanism would not have been able to conduct visits in every State at a frequency sufficient to constitute an effective tool of prevention. By establishing an organism in each Member State, the international committee’s work is complemented by bodies permanently situated within States and therefore able to conduct a continuous work of prevention and to easily initiate a consistent dialogue with domestic authorities. As it regards the NPMs’ nature, the Protocol does not prescribe a single form of mechanism. States are free to design their own institutions in relation to their specific country context, but as long as they ensure the greatest independence of the mechanism from other state powers, obviously conceived as the fundamental requirement to effectively prevent torture and other ill-treatment. To date, the OPCAT has been ratified by 90 States; among them, 71 have designated their NPMs (OPCAT Database, updated at October 2019).

Source: OHCHR and APT

The establishment of the Italian NPM was the final outcome of a long and tortuous path. After the rejection of many legislative proposals, 2013 represented the real turning point towards the establishment of such an institution. In January, Italy was condemned by the Court of Strasbourg for the violation of Article 3 of the ECHR in the Torreggiani and Others v. Italy pilot judgment. According to the European Court, the Italian “structural and systematic nature of prisons’ overcrowding” violated the prohibition to inflict torture and other inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. The ECtHR highlighted the lack of mechanisms allowing an effective protection of detainees’ rights and urged Italy to introduce new instruments or to reinforce the existing ones.

In order to implement the sentence, Italy developed a wide Action Plan adopting several measures aimed at reducing prison overcrowding and generally at addressing the structural shortcomings of its detention system. Among these measures, a few months after ratifying the OPCAT, on 23 December the Italian government enacted the decree law 146/2013 which established, in Article 7, the National Guarantor for the Rights of People Detained or Deprived of Personal Liberty. Soon after, in April 2014, the new organism was appointed as the Italian NPM, along with the other guarantee Institutions operating in the field of deprivation of liberty at the territorial level.

On the CPT model, the National Guarantor was designed as a strong and independent mechanism provided with wide preventive powers. Besides its reactive function consisting in receiving detainees’ complaints, the Guarantor’s main activities are of a proactive nature, carrying out monitoring visits, reporting the relevant findings and making recommendations to the competent administrations.

Given its NPM role, the National Guarantor’s mandate includes any place or situation where people are de jure or de facto deprived of personal liberty. Specifically, the National Guarantor has identified four areas of deprivation of liberty.

The first is of course the one related to detention, of both adults and minors, in virtue of criminal measures. This sector is probably the most known and the most monitored, given the work conducted by surveillance judges, the access of several institutional actors and the significant presence of the voluntary sector. In addition to prison Institutions, the Guarantor monitors the implementation of community and security measures.

The second area, strictly related to the first one, is deprivation of liberty deriving from law enforcement measures adopted for identification or investigation purposes. Specifically, it concerns monitoring of police facilities where people are held under arrest or under preventive detention orders. Even if the stay in a security cell should be as short as possible, in some circumstances it happens that detention lasts longer, including one or more nights. The Guarantor has to monitor whether specific standards are implemented, paying special attention to the conditions adopted in cases of particularly vulnerable people held in custody, such as persons with disabilities, pregnant women, homeless or drug addicts.

The third thematic area is deprivation of liberty in the context of irregular or illegal immigration. Contrary to the previous areas, both connected to criminal matters, in the field of migration deprivation of liberty usually results from administrative dispositions. These are in fact cases of administrative detention ordered for the violation of entry or residence norms. This area implies monitoring of Immigration Removal Centres, hotspots, airport and port facilities. In compliance with the “European Return Directive”, the National Guarantor was designated also as the mechanism in charge of monitoring forced-returns operations of third-country nationals. In the attempt to ensure a more accurate control, the National Guarantor decided to use the support of some Regional Guarantors, especially to monitor the preliminary phases of return procedures, namely those preceding the flight itself. Being established in the framework of the “Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund – AMIF” project, such a cooperation is thereby known as the “AMIF Network”.

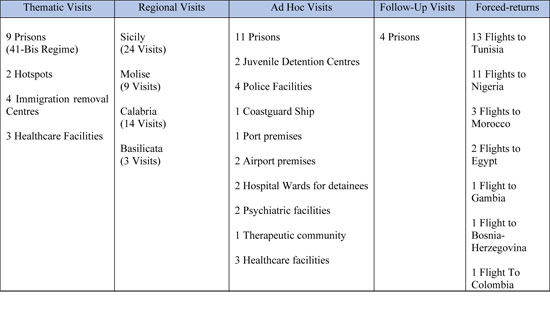

Following the recommendations of the UN Committee for the rights of persons with disabilities, the National Guarantor’s mandate has been further expanded in order to extend its monitoring activity also to deprivation of liberty in healthcare facilities. Healthcare is a sector completely unrelated to any legal or administrative measure where, however, people could in some circumstances undergo factual situation of deprivation of liberty, often because unable to leave. Specifically, the Guarantor mandate includes the monitoring of care home for disabled and elderly people as well as Psychiatric diagnosis and treatment facilities where Compulsory Health Treatments are administered. As for the working method, monitoring activity is carried out by means of regional visits; ad hoc visits; thematic visits; follow up visits; monitoring of return flights.

Source: National Guarantor’s 2019 report. For more information on the National Guarantor’s activities see its 2019 report to the Parliament (Italian version only).

Years before the establishment of the National Guarantor, since the early 2000s, several territorial Authorities decided to appoint guarantee Institutions for the rights of persons deprived of liberty both at the local and at the regional level.

Due to the absence of a clear and specific legislation, the heterogeneity of territorial founding laws has resulted in a proliferation of different institutions with distinct characteristics and powers. The main dissimilarities concern their appointment and removal procedures, the term of office, the scope of mandate and the nature of the institution itself, being sometimes organisms exclusively dedicated to deprivation of liberty and other times Ombudsman with broader purposes.

Once the National Guarantor was established, the Italian government decided to confer the NPM role to the “whole system” of Guarantors. Such a design was aimed at creating an effective network of mechanisms operating across the country and centrally coordinated by the National Guarantor. However, due to the heterogeneity of the large number of territorial Guarantors and the lack by some of them of the fundamental OPCAT requirements, the network is still a work in progress and the NPM role is currently played exclusively by the national Authority.

Since its establishment, the National Guarantor is actively working for the realisation of Italy’s original design. For this purpose, first steps have been made towards the inclusion of some Regional Guarantors, namely those characterised by the greatest conformity with the OPCAT provisions.

Such a decision was not aimed at marginalising the other ones but, rather, at protecting the functioning and the reputation of the preventive mechanism. While territorial Guarantors could represent a powerful instrument to increase the NPM effectiveness, performing a more frequent and consistent monitoring work, the premature inclusion of different - and sometimes not fully independent - Guarantors could eventually undermine the activity of the whole system of prevention.

The very recent launch of the NPM Network project and the large number of actors involved, make any forecast about the future of the Italian preventive mechanism extremely difficult. Clearer conclusions will be probably drawn at the end of the first National Guarantor’s mandate, thereby providing a better picture of the overall progress achieved towards the establishment of the Network.

Source: National Guarantor for the Rights of Persons Detained or Deprived of Personal Liberty

19/11/2019