[

] 149

ering place in 1986 and lent real meaning to interfaith dialogue

in a joint ceremony to pray for peace in Assisi, the city of Saint

Francis, who had himself abandoned the principle of the Crusade.

Just as Pius XI had done in the early 1930s, envisaging a relation-

ship between those who “at least believe in God,” so John Paul II

hoped to show, with the prayer meeting in Assisi, that religions’

contribution to peace did not come about by simply asking each

one to step outside of itself and deposit their individual responsi-

bility in a neutral ground of rights devoid of any past history. On

the contrary, through the very act of religious experience which

characterizes and decentralizes it, namely prayer, each faith was

measured on its ability to find within itself the contribution to the

search for peace that pervades humanity.What was new about this

was not merely the recognition of a common beneficiary of prayer,

but that the sincerity of the person praying was given credit.

Shortly after that prayer meeting, a politological claim which

had been circulating for some time made its appearance in the

context of understanding the

fait religieux.

As early as 1936,

just a few years after Pope Pius XI’s speeches to which I referred

previously, the French Catholic

Semaine sociale

addressed the

theme of ‘the clash of civilizations’. A few years after the inter-

faith meeting in Assisi in 1986, a major American political

scientist posited the theory and dynamics of a new

Clash of

Civilizations.

In his essay and book Samuel Huntington did

not set out to describe an existing conflict or one that was

actively sought. He described a conflict situated along the path

which was leading the world from the end of the Cold War

to the fatal tension between the United States and China, and

which he identified as being somewhere prior to the middle

of the twenty-first century. In Huntington’s view, the halfway

stage of this inevitable struggle for global hegemony would

be the delineation of large geopolitical blocs between ‘civili-

zations’. Within these blocs, the ancient religions which had

all but disappeared in the age of secularization and moder-

nity would once again have a catalysing effect on identity and

would discover a new balance of order (for example solidarity

among Abrahamic monotheistic religions).

Although the prospect of internal conflicts within single

religious groupings was merely the premise for a real war, the

book and its claim were read as the self-fulfilling prophecy of

a clash between Judaism, Christianity and Islam. It is of little

use to point out that since each of the three great Abrahamic

traditions contained so many of these same differences inter-

nally, alongside the memory of bitter or bloody conflicts, to

refer to them as incoherent bodies would be to overgeneralize.

The perceived mutual threat has recruited minds and bodies.

So in the wake of 9/11 the formula ‘clash of civilizations’

seemed perfectly suited to describe the struggle. On the one side

those within the various spiritual traditions of Islam who have

attempted armed insurrection and whose victims have mostly

been other Muslims, considered harmful to a regenerative and

purifying idea of violence (a typical idea in pre-1914 Europe). On

the other, the West, riddled with differences no less radical than

those intra-Muslim ones, but perceived and acting as the bearer

of an identity with religious overtones of its own.

There are some who have tried to hold out against the idea of

a slow slide into the

bellum perpetuum

as theorized by Francisco

de Vitoria 500 years ago. An array of centres and institutions, of

passion and intelligence, of souls and ideas has been deployed to

bring the first mile of interreligious dialogue to completion, with

increasingly significant results: these efforts were sustained both

by the intent of combating that ‘30-years war’ between Islamic

minorities who, within divided traditions, dream of regenerat-

ing a mythical past unity, and of limiting the power of political

groups in the West who have fought terrorism (the terrorism

in the name of God) and thus justified wars and warfare which

violate the fundamental principles of democratic states.

This first mile has consisted of well-meaning intentions

and sincere commitment in order to educate public opinion,

both inside and outside Europe, that fraternity is possible.

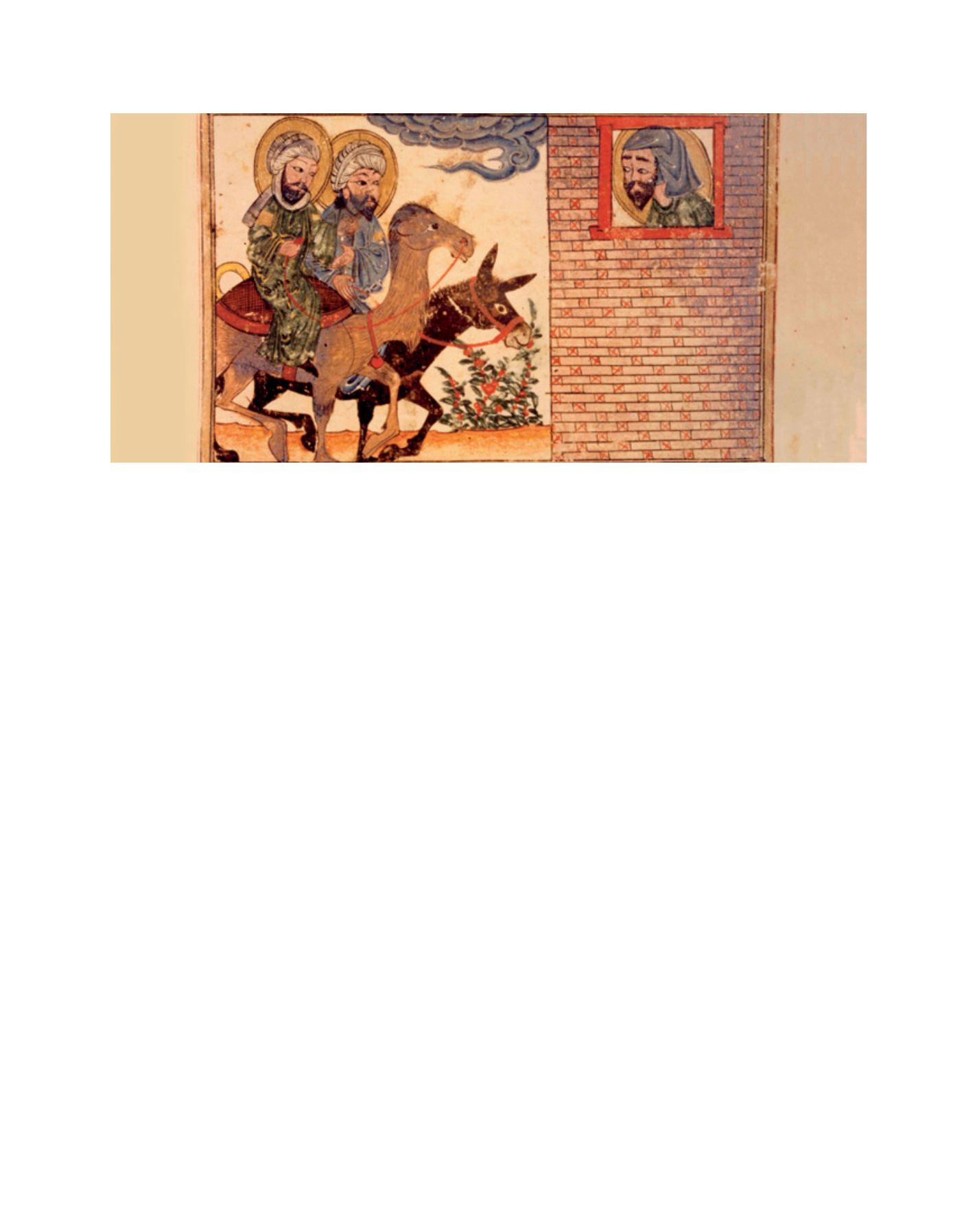

Isaiah’s vision of Jesus riding a donkey and Muhammad riding a camel, al-Biruni, al-Athar al-Baqiyya ‘an al-Qurun al-Khaliyya (Chronology of Ancient Nations),

Tabriz, Iran, 1307-8

Image: Edinburgh University Library

A

gree

to

D

iffer