Universal Design and Environmental Sustainability: Synergies for an Inclusive and Sustainable Architecture

Within contemporary architecture, the concept of environmental sustainability should by now be an undisputed priority. However, alongside debates on energy efficiency, eco-friendly materials, and emissions reduction, the theme of Universal Design (UD) is often confined to a separate domain, regarded primarily as a matter of accessibility and social inclusion.

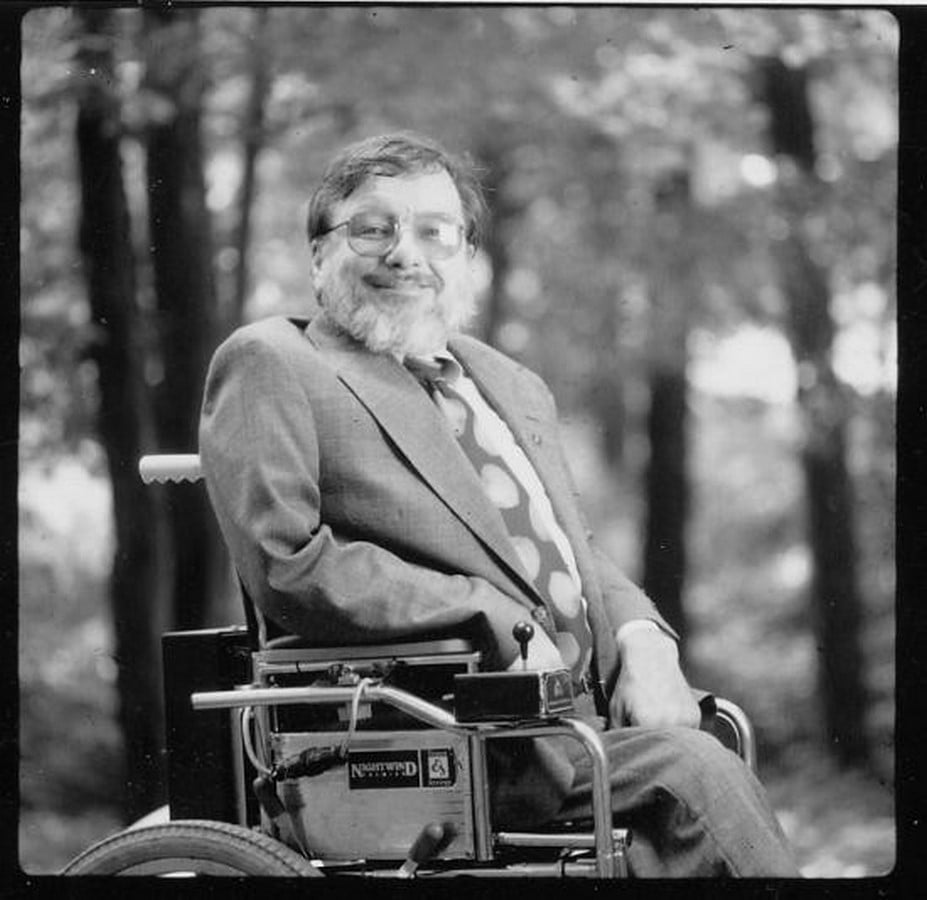

The concept was introduced by the American architect, designer, and lecturer Ronald L. Mace (1941–1998), who, at the age of nine, contracted polio and was required to use a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Mace personally experienced the barriers faced daily by persons with disabilities, from bathroom doors too narrow to accommodate his wheelchair to the impossibility of independently attending classes held on upper floors (he had to be lifted and carried up and down the stairs). This did not deter him, and after graduating in 1966, he was among the first to propose a revolution in the way accessibility was understood: no longer as an additional feature designed “for a few”, but as an intrinsic quality of design, valid for everyone.

In 1989, Mace founded the Center for Universal Design at North Carolina State University, contributing to the definition of the Seven Principles of Universal Design, which still serve today as a compass for architects, designers, and policy makers:

- Equitable use – The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities.

- Flexibility in use – The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

- Simple and intuitive use – Regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or concentration level.

- Perceptible information – The design effectively communicates necessary information, regardless of the user’s sensory abilities.

- Tolerance for error – The design minimises hazards and adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

- Low physical effort – The design can be used efficiently and comfortably with minimum fatigue.

- Size and space for approach and use – Appropriate size and space are provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of the user’s body size, posture, or mobility.

Universal Design is a design approach that makes environments, products, services, and technologies accessible, understandable, and usable by the greatest number of people, regardless of age, gender, culture, education, or motor, sensory, or cognitive abilities. Rather than retroactively adjusting existing spaces, it adopts a proactive, integrated approach to eliminate barriers and ensure inherent inclusivity in all spaces and tools.

Sometimes, a solution for one person creates a barrier for another, while a solution designed for everyone does not constitute a barrier for anyone.

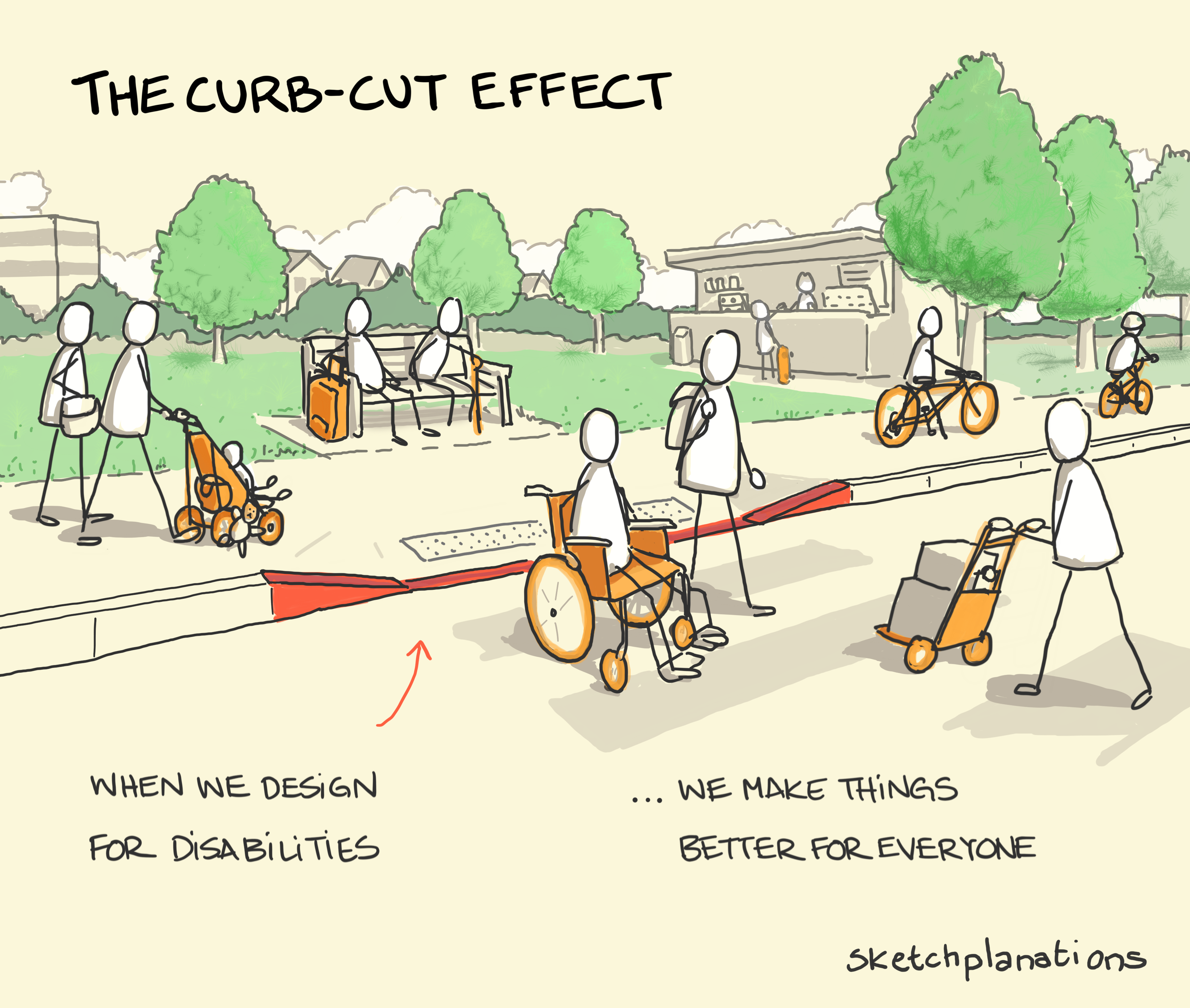

A well-known example is the electric toothbrush: invented in 1939 for people with limited motor skills, it only began to gain popularity in the 1960s. However, its production remained limited due to scepticism and high costs, which still prevented access for most users. From the 1980s onwards, thanks to technological developments that made production cheaper and thus more accessible to consumers, its use increased exponentially. Similarly, kerb ramps are useful not only for people with mobility difficulties, but also for those using prams, suitcases, bicycles, and so forth.

How, then, can Universal Design actively drive environmental sustainability in architecture—not simply as parallel values, but as interdependent principles that, when combined, deliver greater social and ecological benefit?

In today’s world, marked by social, climatic, and economic challenges, architects and designers have an increasingly strong ethical responsibility: to design buildings, spaces, and products that respect the environment without compromising user well-being and accessibility.

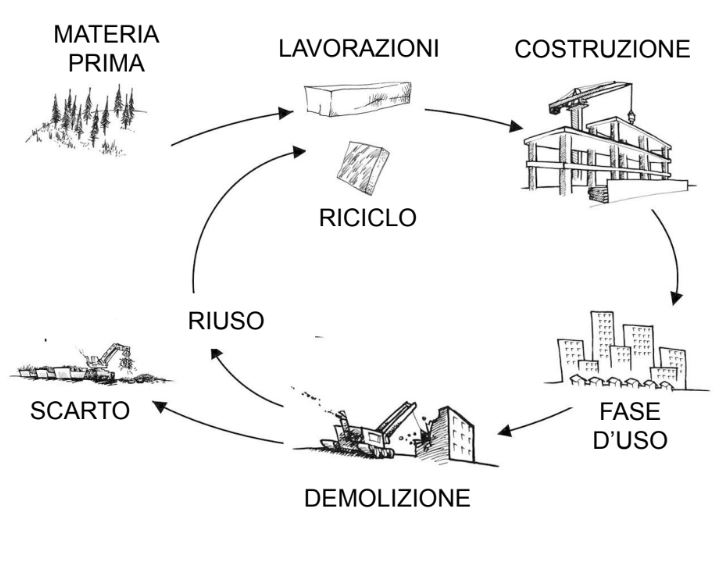

When we think of a “sustainable building”, elements such as low energy consumption, solar panels, or natural and recycled materials often come to mind. While these undoubtedly improve energy efficiency, a more systemic vision is required to evaluate a building’s environmental impact. Sustainability, in fact, should be assessed by considering the entire life cycle of a building: from the extraction of raw materials, to transport, production, daily maintenance, and ultimately disposal or recovery (“from cradle to grave”).

This vision underpins the LCA (Life Cycle Assessment) methodology – an evaluation of the life cycle of a building or product which allows architects, suppliers, clients, and public authorities to make more informed decisions through the analysis and quantification of environmental impacts associated with all its life phases.

In the construction field, this means considering aspects such as:

- The environmental impact of raw material extraction and transportation.

- Energy consumption over the entire lifespan of the building.

- Durability and adaptability over time (resilience).

- The costs and environmental impacts of demolition, recycling, and final disposal.

A building designed according to UD principles is often more flexible, durable, and resilient: qualities that reduce the need for future modifications, extend the life of structures, and minimise waste and invasive interventions.

Adopting modular design fosters flexibility in the subdivision of spaces, making them easily adaptable to changing user needs over time and reducing the need for demolitions and/or extensions.

The optimisation of natural lighting and ventilation reduces energy consumption while at the same time creating healthy, inclusive, and comfortable environments, where users should always retain a certain degree of control over their surroundings.

Multifunctional design also allows for more efficient use of spaces, both throughout the day and across the life cycle of the building. Spaces can be shared among different groups, adapt to diverse needs, and contribute to more effective energy use.

A concrete example is that of school buildings: if designed appropriately, they can host educational activities during the day and be open to the wider community in the evening, at weekends, or in the summer months, ensuring inclusion, comfort, and safety for all users.

In this sense, Universal Design is not merely an ethical choice, but a concrete strategy for making the built environment more sustainable. An accessible, flexible, energy-efficient, and adaptable building consumes fewer resources, lasts longer, and serves the community better. It is therefore not just a matter of designing “for all”, but of designing better: with intelligence, foresight, and respect for the urban and environmental context.