However it is easier said than done for the reasons enunci-

ated above: since the Westphalian treaty, states actions are

defined on secular principles in the international arena.

There is therefore a strong secular culture that prevents or

inhibits governmental and international agencies to take

into account the religious dimension of peace building,

conflict resolution and any form of positive development.

The main reason for this inhibition is related to the domi-

nant but false perception that religious groups and actors

are not as rational, nor inclined to compromise, as non-

religious ones. This perception is reinforced by a primary

focus on religious texts and ideologies to apprehend reli-

gion and politics which disregards the empirical reality of

the ‘belonging’ and ‘behaving’ of religious individuals and

groups. It also neglects the crucial influence of political

and cultural contexts that fashion and shape the readings

and interpretations of religious texts. In other words, the

understanding of the context in which religious actors are

operating is key to identifying the ones that could support

international initiatives in favour of peace or rapproche-

ment. It also means that such international policies

inclusive of religion will require specific information and

understanding that cannot be gathered in the high peak of

crisis or conflict but rather through a prior understanding

of religion across nations and regions. In this regard, the

very rich and diverse information on and from religious

groups in different national and regional contexts is an

important resource that should be gathered by an interna-

tional agency such as UNESCO in order to be available to

international organizations and state actors during times of

crisis. It would also be critical to create a global network

of religious groups and actors of all denominations and

traditions who work locally in favour of peace, economic

development and social justice. The key word here is ‘local’.

Too often, the action of religion at the international level

consists of high profile religious figures signing a document

enunciating the broad principles of peace and tolerance. In

most of the cases, these documents do not have any impact

on the ground. For example, the Amman Message, initiated

by the King of Jordan in 2004 is a remarkable document

bringing prominent Muslim figures to assert or re-assert

the tolerance of the Islamic message. Regretfully, this docu-

ment is not known or referenced by religious actors in

different localities. In contrast, a more positive action led

by an international organization would create a continu-

ously updated repository of resources and information on

religious groups and actors who are not automatically reli-

gious scholars and authorities but who act positively in the

name of religion. Such an international observatory and

database does not have to be built from scratch. It can take

advantage of the existing information and data from the

national levels and international religious organizations.

When world leaders met in the year 2000 at the United

Nations, to identify major challenges for the new millen-

nium, they did not include religion as a tool of economic

and political development. Introducing religious actors and

organizations into policymaking is certainly sorely needed

to overcome the one-sided perception of religion as the

problem for national and international peace.

on recommendations for a document and process in the

United Nations that would lay out actionable and meas-

urable goals to reduce interreligious and intersectarian

violence. Participation and support have included His

Royal Highness Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad of Jordan,

His Holiness Pope Francis, His Royal Highness the Prince

of Wales, His Eminence the Archbishop of Canterbury, His

Beatitude Patriarch Theophilos of Jerusalem, former Chief

Rabbi of the United Kingdom Lord Sacks, Rabbi David

Rosen, Sheikh Abdullah bin Bayyah, His Eminence former

Grand Mufti of Egypt Sheikh Ali Gomaa, former President

of Ireland Mary MacAleese, His Eminence the Nigerian

Sultan of Sokoto Sa’ad Abubakar, Director of Shanti Asram

Doctor Vinu Aram and Supreme Patriarch of Cambodia the

Venerable Tep Vong, among other high-ranking officials

and scholars.

In the same vein, religious groups and actors are

important in economic development. It has been amply

documented that the Sufi group, Tidjaniyaa, has been

central in the development of peanut agriculture in Senegal.

The role of Catholic and Protestant groups such as Bread

for the World and Misereor in the economic development

of entire regions in Africa, Latin America and Asia has also

been significant. But religious groups are rarely invited to

any international discussion on economic development or

climate change.

Another neglected aspect is the influence of religion on

democracy. For example, three quarters of the countries

of democratization’s ‘third wave’ were Catholic. While not

all local Catholic churches supported democratization, the

Second Vatican Council’s endorsement of Human rights in

1963 and Pope Paul VI’s 1965 Dignitatis Humanae, which

declared religious liberty a basic right rooted in human

dignity, certainly played a role in this endorsement. This

was a significant change from the Church’s previous oppo-

sition to democracy and even the Westphalian state.

In these conditions, it is imperative that leaders take

religions seriously both domestically and internationally.

Religion can be a source for civility, especially at the level of local

communities, too often neglected by policy makers

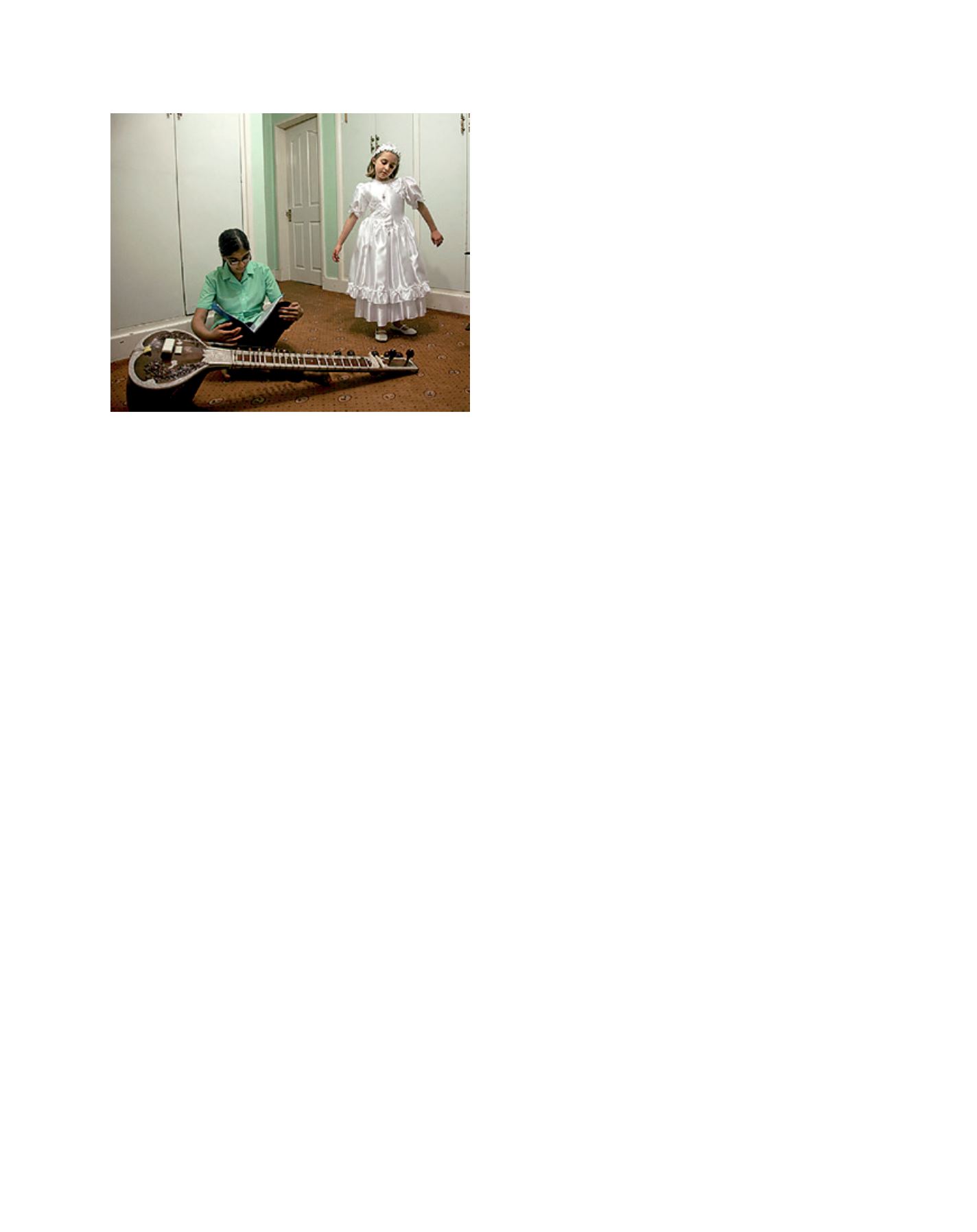

Image: Liz Hingley

A

gree

to

D

iffer

[

] 102