[

] 101

is an admirable one, but it must not be done through a

reification of both culture and civilization.

This ahistorical approach to Islam’s global role affects all

other religions and their role in international relations.

2

Most of the time, religious manifestations are seen as ideo-

logical phenomena – that is, as ideas or beliefs. Such an

approach reduces religion to a rhetoric that is used in

political mobilization and hence gives the illusion that the

knowledge of concepts and symbols of religious traditions

is the major way to understand their role in politics.

To overcome this essentialization, it is important not to

reduce religion to beliefs or texts. Doing so, does not allow

an understanding of how and when it can be positive and a

tool for rapprochement. For example, young Muslim activ-

ists in South Africa fought against apartheid alongside other

religious communities and justified their fight through an

interpretation of the Ummah (community of believers) as

synonymous with a more inclusive South African nation.

Today, the same references are used by radicals like ISIS to

divide and fight. So the religious texts do not explain politi-

cal conditions, unless we take into account the contexts:

the cultural and historical conditions that inform the

behaviours and interpretations of the believers.

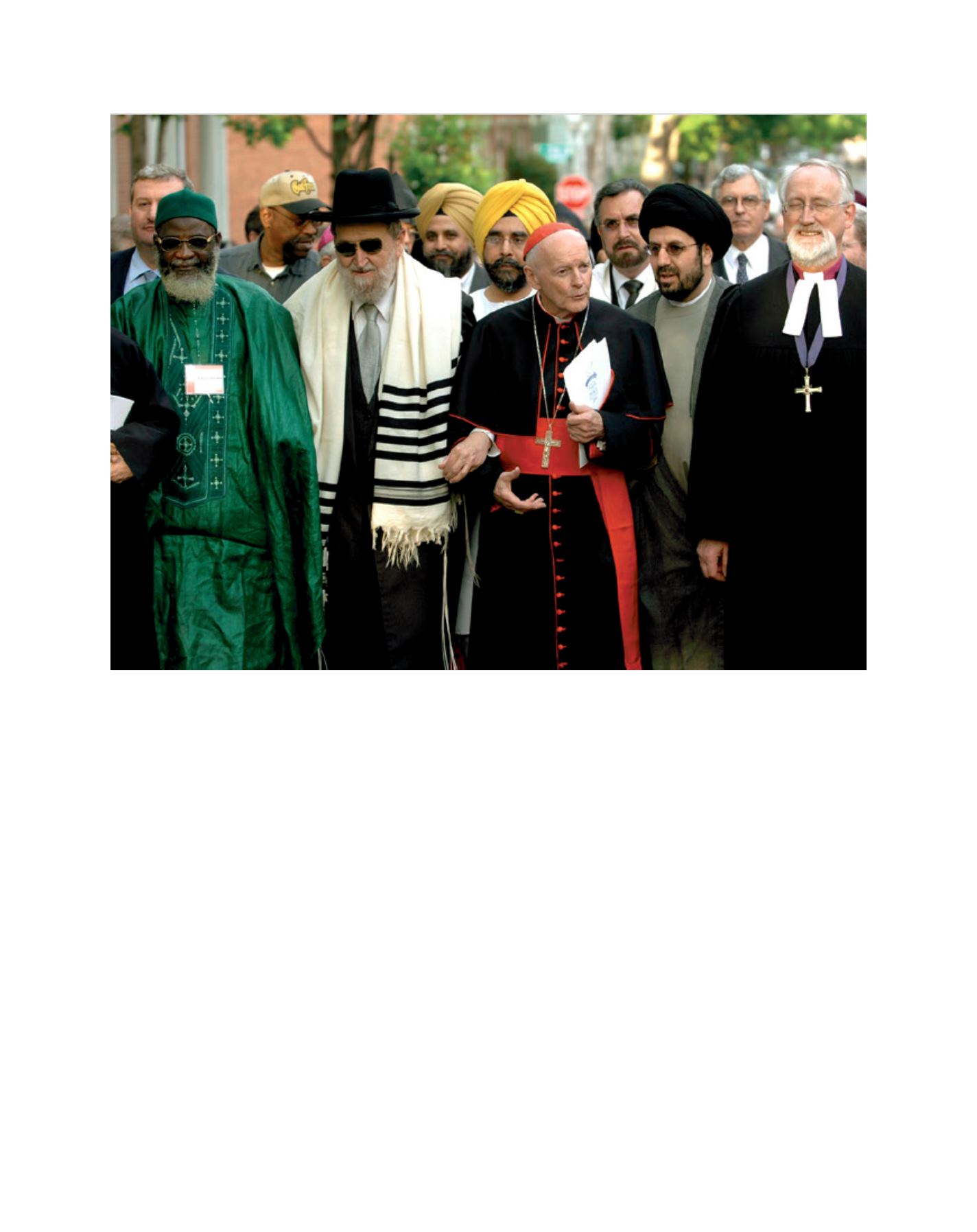

More generally, it is imperative to include religious actors

and groups in any attempt at conflict resolution. Since the

mid twentieth century, several global movements for inter-

religious peace have broken barriers between the world’s

leading religions and among governmental, civic and reli-

gious leaders. For example, Religions for Peace (established

in 1970) has played a significant role in hosting peacebuild-

ing conventions among religious leaders, United Nations

delegates and representatives of state governments; and

the Christian Community of Sant’Egidio (established in

1968) has, in addition to its services for the poor, played

a noteworthy role in mediating peace negotiations in

Mozambique, Algeria and elsewhere. Encouraged by such

movements, a number of religious leaders have, increas-

ingly over the past five to ten years, called for direct

cooperation among the world’s religions to renounce inter-

religious violence and nurture interreligious peace. Recent

statements by the emergent Global Covenant of Religions

serve as a prototype for these calls.

In April 2014, His Majesty King Abdullah invited reli-

gious scholars, faith leaders and diplomats to Amman to

respond to calls for a ‘Global Covenant’ and to form a

steering group – the ‘Ring of Faiths’ – to work together

Image: Georgetown University

Since the mid twentieth century, several global movements for interreligious peace have broken barriers between the world’s leading religions and among

governmental, civic and religious leaders

A

gree

to

D

iffer