[

] 110

Hence, human rights-based citizenship is a plural citizen-

ship which, unlike traditional national citizenships built on

the premise of excluding foreigners

(ad alios excludendos)

,

is characterized by the premise of including human beings,

any human beings

(ad omnes includendos).

A tree metaphor

can help illustrate this. The trunk represents the status of

universal citizenship, the roots are universally recognised

human rights, and the branches are derived citizenships

(national and sub-national), which, in order to survive,

need to absorb the life-giving sap running up through the

trunk; that is, they must be consistent with the egalitarian

nature of universal citizenship. Redefined thus, where the

overarching parameter is the

ius humanae dignitatis

(the

right to human dignity), there is clearly no room for the

discriminatory

ius sanguinis

(right of blood). For admin-

istrative-civil registry purposes, the determining factor is

a non-nationalistic interpretation of the

ius soli

(right of

the soil). All this requires a radical overhaul of national

laws, starting from those on immigration. It is not an easy

journey and it will take a long time for racism, nationalism

and ‘war hero’ attitudes to be subdued, but it is time to start

working on it.

There are several initiatives heading in this direction

in Italy, promoted by academics, local authorities and

civil society organizations and which, in many cases, go

beyond the limits of national laws. For example, some local

administrations grant honorary citizenship to immigrants’

children regardless of the legal or illegal immigrant status

of their parents; others present all school pupils, includ-

ing immigrants’ children, with a certificate as ‘pioneers of

plural citizenship’. The principle to which they make more

or less explicit reference is that of ‘the best interests of the

child” set forth in Article 3 of the International Convention

on the Rights of the Child.

As is well known, since 1992, plural citizenship has

existed within the European Union’s (EU) legal-territorial

space, comprising a national citizenship and a European

citizenship deriving from the former: one is a citizen

of the EU if one is a citizen of an EU member state. So

although this citizenship is not directly grounded in human

rights, and despite its reproducing the

ad alios excludendos

premise, it is still a sign that citizenship can be made plural.

It should be noted that the EU is a thriving laboratory of

multi-level governance, which has adopted its own EU

Charter of Fundamental Rights, the central figure of which

is the human person as such. Taking into consideration

the constitutionally evolutionary vocation of the EU, the

University of Padua Human Rights Centre is advocating for

a uniform European law that, starting from the EU Charter,

would invert the relationship between EU citizenship and

national citizenship, making the former primary and the

latter derived citizenship. Its strapline is: “why a single

currency (the Euro) and why not a single European human

rights-based citizenship for all member states?”

Image: Coordinamento Nazionale Enti Locali Pace Diritti Umani

The Palais des Nations in Geneva: a delegation of mayors delivers a copy of the first 100 motions on intercultural dialogue approved by local councils

A

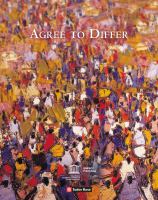

gree

to

D

iffer