[

] 111

Peace and plural citizenship are at the same time both a

precondition for and the outcome of intercultural dialogue.

But peace is a human right according to the

vox populi

(voice of the people), not yet recognized as such under

international law. In order to fill this yawning gap, since

2012 the United Nations Human Rights Council is drawing

up a declaration on the right to peace, recognized as a

fundamental right of individuals and of peoples. This new

international instrument should in particular detail the obli-

gations of the principal duty bearers, the states: first of all

to fully implement the United Nations Charter, to finally

make the collective security system work, to carry out real

disarmament, starting by controlling arms production and

trade. Unfortunately, the council’s admirable initiative is

meeting strong opposition, even from states which have a

long tradition of respecting the rule of law, human rights

and democratic principles. In short, they want to continue

to keep the right to peace

(ius ad pacem),

as an attribute of

their sovereignty, closely tied to the much stronger attrib-

ute which is the right to go to war

(ius ad bellum).

History

proves that they make an ill-fated pair. The issue now is to

free peace from the clutches of warmongering sovereignty

claims and to bring it into the healthy area of human rights.

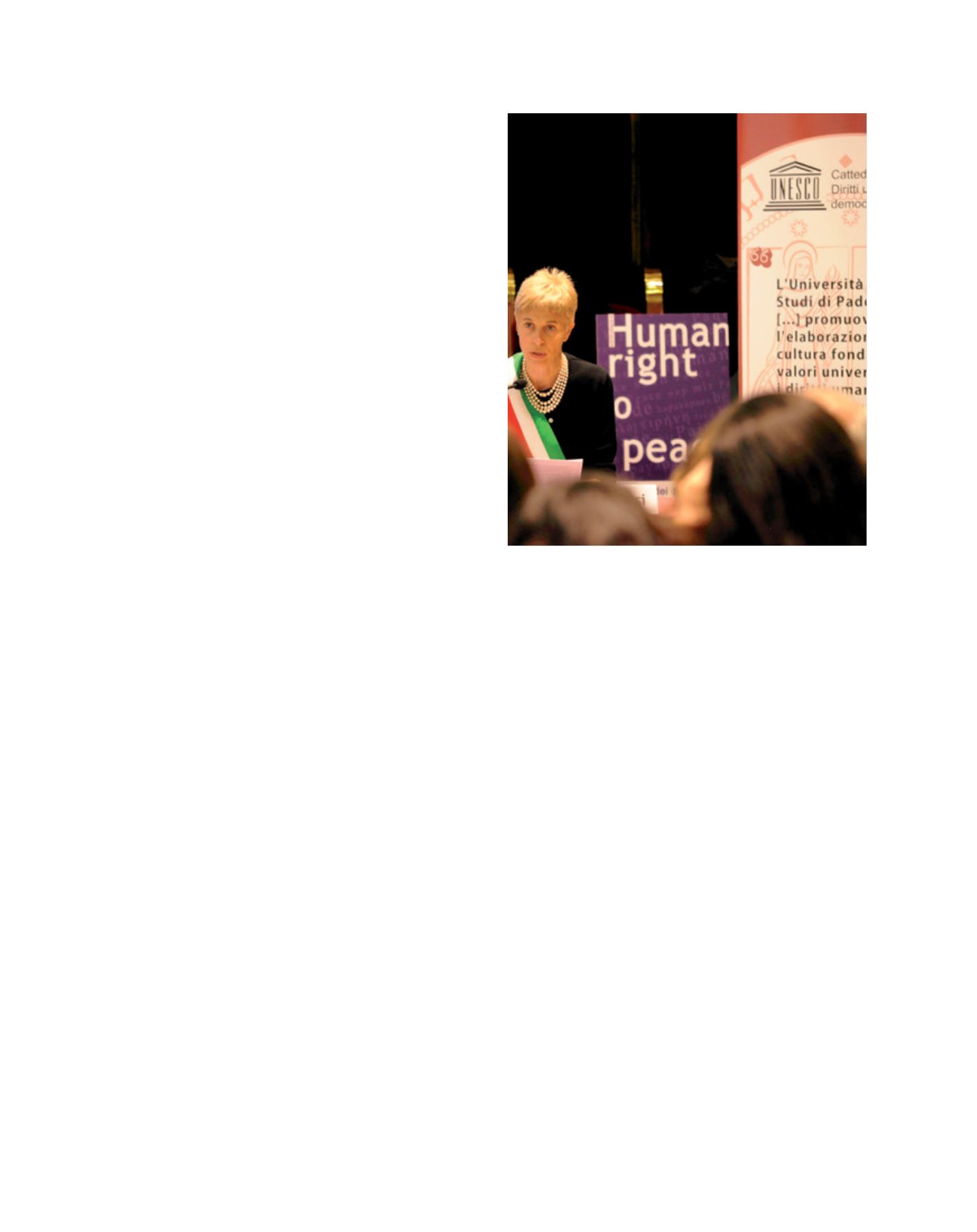

A broad transnational civil society movement has recently

gone into action, linking the right to peace to the supreme

right to life. In Italy this has taken the original form of city

diplomacy. Hundreds of local authorities, following resolutions

approved by their respective councils, have adopted a petition-

ary motion drawn up by the University of Padua Human Rights

Centre and the UNESCO Chair on Human Rights, Democracy

and Peace, together with the National Coordination of Local

Governments for Peace and Human Rights.

It is significant to note that the local authorities which

have worked for the recognition of the right to peace are

running programmes on intercultural dialogue in their

respective locations. The petition has been sent to the

representatives of the member states of the Human Rights

Council. Further, a delegation of mayors has travelled to the

Palais des Nations in Geneva to deliver a copy of the first 100

motions approved by local councils.

In addition to the principle of subsidiarity to be upheld

in the global political space, this action by local govern-

ments beyond state borders is formally legitimized by

Article 1 of the 1998 United Nations Declaration on the

right and responsibility of individuals, groups and organs

of society to promote and protect universally recognized

human rights and fundamental freedoms, as follows.

“Everyone has the right, individually and in association

with others, to promote and to

strive

for the protection and

realization of human rights and fundamental freedoms

at

the national and international levels”

(italics added). This

same United Nations Declaration, which is considered

the charter of human rights defenders, who are genuine

pioneers of universal and plural citizenship, also legitimizes

new approaches and actions to ensure due consideration

is given them: “Everyone has the right, individually and

in association with others, to develop and discuss new

human rights ideas and principles and to advocate their

acceptance.” Plural citizenship and city diplomacy can

legitimately be included under this provision, which has

a logical and productive link with the prospect of creating

“shared cultural expressions” such as those advocated by

the UNESCO Convention on cultural diversity.

The human rights paradigm extols the life and dignity

of all members of the human family. It is hardly neces-

sary to point out that war not only causes the violation of

all human rights, but it kills the original holders of those

rights: it is a collective death sentence. This is why the

cultural dialogue agenda must necessarily include the

issue of world order, together with that of citizenship and

social cohesion at the local level. Article 28 of the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights provides us with a general

model when it states that “everyone is entitled to a social

and international order in which the rights and freedoms

set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.” This rule

implicitly contains the definition of positive peace, which

is built along a road which leads from the city up to the

United Nations.

The current examples of city diplomacy illustrate the

effort being devoted to building peace from below –

“bottom-up peace” – not against but in support of the

‘good’ diplomacy of states. The on-the-ground experience

of building bridges between the different cultures present

in cities, starting from the supreme right to life and from

the basic needs of all the people who live there, consti-

tutes a fundamental resource which can help translate the

logical interconnection between social order and interna-

tional order, as in the aforementioned Article 28 of the

Universal Declaration, into hard facts, to the benefit of all

human rights for all.

City and University, a fruitful alliance for a human rights to peace culture

Image: University of Padua-Human Rights Centre

A

gree

to

D

iffer