[

] 53

nation and promote women’s socioeconomic autonomy and

societal acknowledgement of tasks that should be shared, such

as care-giving for example. The social and political dynamics

of gender determine the degree to which women feel part of

society or in tension with the existing order. In the words of

Nelly Richard, belonging thus oscillates between ‘being part

of’ and being ‘in tension with’.

The link between identity and sense of belonging is

constructed by complex interactions between the indi-

vidual, society and politics: belonging and identity are not

natural phenomena, but are built upon narratives, discourse

and politics and are subject to dynamic processes of differ-

entiation. Self-referential identities cannot exist for either

individuals or societies, since all identities draw on political

and social ‘material’. Moreover, when identities are expressed

across society, the fact of identifying with a group in no way

exhausts the individual identity of its members; individual

identities coexist virtually within groups and in their many

points of reference. The diversity of and social interdepend-

ence between the identities and senses of belonging of each

member of society can be related to the likelihood of altru-

ism and involvement with the law, and to the capacity for

mutual identification and respect. In contrast, fundamental-

ist expressions of identity militate against such plurality and

are generally the product of a homogeneous and mythified

vision of one’s self. Such a view is generally accompanied by

an equally reductionist corollary, the negative representation

of the identity of ‘the other’.

This is why it is so important to make plurality of life forms

a political foundation of the sense of belonging. Respect for

individuals within a democracy is based on treating them as

abstract holders of fundamental rights, such as civic equal-

ity; and providing them with an inclusionary matrix for their

choices represents a challenge for democracy as a political

system. A sense of belonging is part of subjectivity, and iden-

tity has to do with ethical choices. Plurality of lifestyles can

be a fundamental principle of truthfulness in discussions on

values, as it is a cornerstone of reciprocal recognition and

therefore alludes to the rules governing interaction.

In view of these challenges and current tensions, thought

should be given to the foundations of democracy, because

“civic equality, liberty, and opportunity are core principles of

any morally defensible democracy”, as Amy Gutmann points

out.

3

In this regard, individuals are the ultimate subjects of

morality and, as such, the incarnation of these three demo-

cratic principles. The principle of civic equality constitutes an

obligation to treat all individuals as equal agents of democracy

and to create the necessary conditions for the equal treatment

of citizens. This is consistent with the principle whereby civic

equality is a right that may be exercised only collectively, rather

than individually; this is because it equates to being treated as

a citizen who is equal to others. Although this presupposes the

possibility of individuals joining together to form groups, the

desired beneficiary and the claimant of the right is the individ-

ual, not the group. Secondly, the right to equal freedoms obliges

the democratic order to respect the freedom that all individu-

als have to live their lives as they see fit, provided that this

does not impinge on the same measure of freedom for others.

Lastly, there is the principle of basic opportunities: the capac-

ity of individuals to lead a dignified life, with the possibility of

choosing whatever lifestyle they wish. The political expression

of belonging to a given group must be compatible with the exer-

cise of human rights for those ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ it, namely

in the relationships its members cultivate with one another and

with society as a whole. Within this framework, fundamental

human rights ensure respect for individuals in conditions of

civic equality and in their capacity as agents of purpose with

equal freedom to live their lives as they see fit. Group rights, far

from threatening human rights, are derived from two of them:

the rights to equal freedoms and civic equality. When people

exercise their freedoms of expression, association and transit

and enjoy the benefits of a free press, their choices extend

beyond their immediate surroundings.

Identities emerge and are demarcated in an inherently

conflictual political process that entails mutual recognition

and delimitation, and requires the formal definition of the

range of permitted behaviours. It is therefore crucial that the

democratic organization take account of social diversity and

confer formal legitimacy upon it. If democracy is understood to

be the institutional sphere encompassing, and the institutional

rules governing, egalitarian processes of identity construction,

no one can claim to exclusively represent any given identity or

any subordinate groups that have been excluded throughout

history. It is therefore important to consider how the tension

between equality and difference affects the quality of democ-

racy in a globalized world, in which people continue to need

communities, bonds and meaning for their lives. It is here that

life as a whole poses a further major challenge: openness to

pluralism, the political expression of respect for others, the

quest for fundamental bonds and inquiries into the unity of

the self – all engender in return a yearning for identification

with other human beings.

4

It is important to consider how the tension between equality and difference

affects the quality of democracy in a globalized world

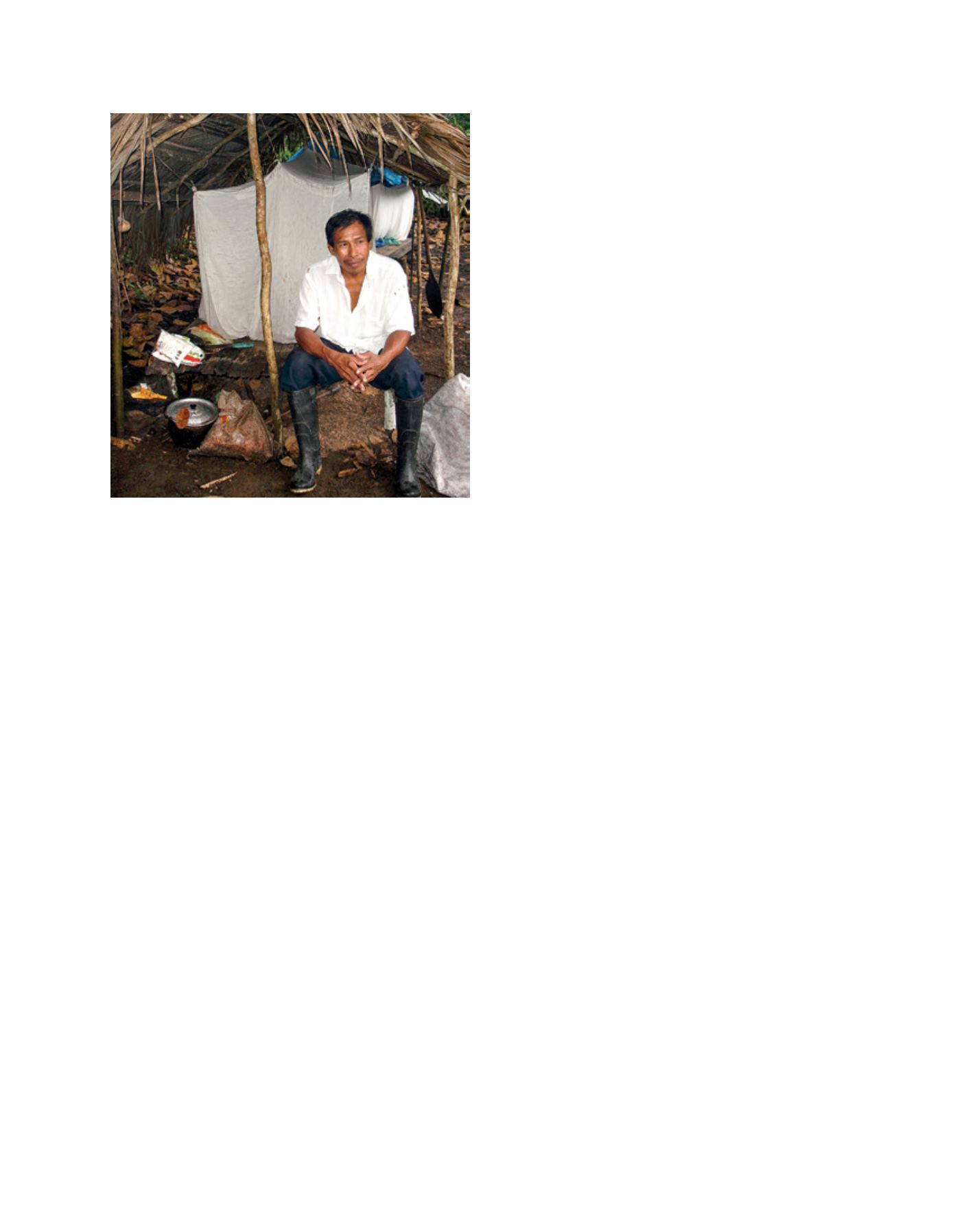

Image: María Elisa Bernal

A

gree

to

D

iffer