[

] 47

the World Council of Churches (created in 1948). The second

is the post-Shoah Jewish-Christian dialogue. The third is the

loss of power of Western European churches regarding the

political institutions of post-Second World War nation states,

increasingly secularized. These three concomitant transforma-

tions led most mainline churches to start to take the ‘dialogue

turn’ from the middle of the twentieth century onwards.

The third social transformation, the (initially European/

Western) political secularization process, came to domi-

nate the culture of the new international community, as

reflected in the growth of the United Nations. The language

of the founding documents of many United Nations agen-

cies, such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and

Cultural Organization, reflect a secular discourse rooted in

the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Intercultural

dialogue, including inter-ideological, has since been the goal

to achieve in international circles. So two, often parallel,

dialogues developed in the last half century: intercultural and

interreligious, the latter being promoted mostly by Western

or westernized churches and other Western minority reli-

gious communities, such as Judaism. In the latter half of the

twentieth century, interreligious dialogue broadened its scope

in response to both increased religious diversity in the West

(due to immigration) and to growing awareness of dialogue

in countries with centuries of religious diversity. This has led

to the emergence of several kinds of interreligious dialogue

organisations, a trend that continues to this day.

In all other regions of the world, especially sub-Saharan

Africa and many regions in Asia, religious plurality has been

a defining characteristic of local and transnational history

for millennia. However, its management from a political

perspective has encountered modernization challenges similar

to those initially faced in the West, arising initially, under

both the post-colonial dynamics of independent nation-

state building and, more recently, post-Cold War openness

to address the challenges of cultural and religious plural-

ity, in addition to ideological differences. Many initiatives

have emerged, such as: the leadership role of the Japanese

Buddhist lay religious organization Rissho Kosei-kai in the

hosting of the World Conference on Religion and Peace

(1970) that has led to the establishment of Religions for Peace/

International (based in New York City); the World Fellowship

of Interreligious Councils (India, 1988); the Royal Al-Al-Bayt

Institute for Interfaith Studies (Jordan, 1988); the United

Religions Initiative (2000); the Alexandria Process (2002);

the Doha International Center for Interreligious Dialogue

(2003); the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations (2005);

United Nations Resolution A/61/221 entitled ‘Promotion of

interreligious and intercultural dialogue, understanding, and

cooperation for peace’ (2006); A Common Word (2007); the

Mecca Appeal for Interfaith Dialogue (2008) and the King

Abdullah Bin Abdulaziz International Centre for Interreligious

and Intercultural Dialogue (KAICIID), to name only a few.

In order to avoid falling into often reductive binary debates

(such as East-West, Liberal-Communist or Secular-Religious),

dialogue has emerged as a more flexible tool to address the

many facets and at times conflicting interests at the heart of

modernization challenges. |In this context, and more or less

worldwide, dialogue has become a social and political means

(soft power) to foster greater mutual understanding between

a variety of different identity groups and communities, as well

as to enhance effective collaboration towards common citizen-

ship, whether at the national or global levels.

Both interreligious and intercultural dialogue are

contributing to a paradigm shift away from debates that

aim to win arguments for greater subsequent control of

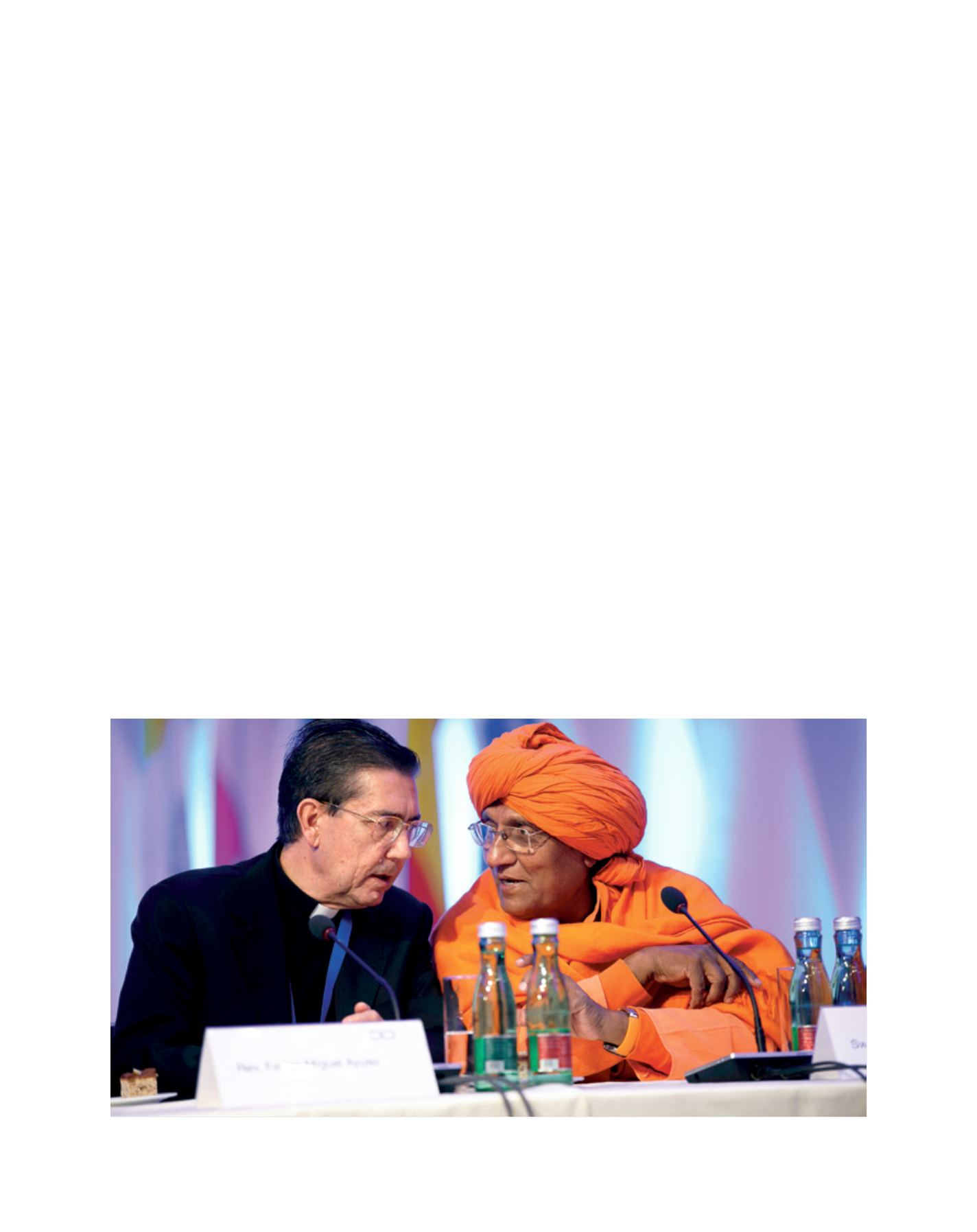

KAICIID board members Father Miguel Ayuso and Swami Agnivesh share their experiences of interreligious and intercultural dialogue and education

Image: KAICIID

A

gree

to

D

iffer