[

] 69

In a paper by Herson Huinca Piutrin, titled ‘The Mapuche of

the Acclimatization Garden of Paris in 1883: objects of colonial

science and contemporary investigation policies,’ there is a clear

description of one of the most brutal and inhumanmuseographic

experiences in the world: the human zoos. It describes the expe-

rience of 14 men, women and children, who were removed from

Lafkenmapu (specifically from the city now called Cañete) and

taken to Paris, a key city in the nineteenth century for expositions

of technology advances and human beings that were considered

exotic and strange to colonial eyes. Treated as science objects,

these people were exhibited and became a popular spectacle.

Huinca Pitruin highlights the fact that this kind of exhibition,

combined with mass media, the scholar system and literature of

that time, helped a French colonial culture that thought it was

a carrier of humanity and civilization. In attempting to show a

contrast between a developed civilization and a rudimentary one,

these kinds of expositions helped justify the French spirit and

actions towards the colonization and conquest of other countries

in America, Africa and Asia.

The social imaginary of an ‘other’ built under scientific theori-

zation suggested an inequality of races that placed the white race

as a superior one. Huinca Pitruin mentions that “it is estimated

the realization of 40 ethnologic exhibitions were carried out and

produced in the heart of the Acclimatization Garden of Paris

between 1877 and 1931,” including groups of Africans of Nubian

origin, Greenland Eskimos and Argentinian gauchos. Huinca

Pitruin contends that Mapuche society is still being studied as an

object rather than as a subject. While in the present we don´t have

an example as radical as the human zoos in nineteenth-century

Paris, there is still a brutal exclusion of Mapuche society in terms

of culture, language, religion, etc. These exclusions deepen the

territorial conflict that has existed in Chile for 500 years.

When you arrive at the Mapuche Museum of Cañete you

notice a big mural with pictures of many Mapuche people: old,

young, children, rural and urban people. On that wall you can

read many welcoming messages in mapuzugun, the original

language of the Mapuche people. This wall was a request from

the people of the local Mapuche communities to the museum.

They wanted Mapuche people to be welcomed with messages

in their own language, as the museum really belonged to them.

Juana Paillalef Curinao is the director of the Museo Mapuche

de Cañete. She is a Mapuche woman, and she welcomes her

guests in her own language. When she sees the confused faces

of the people who do not recognize any sound or word of what

she is saying, she probes the fact that in Chile we still don’t have

a real intercultural dialogue: “In Chile, after 500 hundred years

of an alleged cultural relation, Chileans still don’t know anything

about the Mapuche culture. This wasn’t a cultural encounter; in

a cultural encounter both sides learn from the other and respect

each other.” Juana Paillalef studied education at Universidad de

la Frontera in La Araucanía. After doing an internship in the

local museum, she worked for many years in its education area.

She tells of her first impression of that museum: “I started work

at the Regional Museum of Araucanía in 1980. As a Mapuche,

something that seemed counterproductive to me was the fact

that I saw things in the museum cabinets that I still used in my

normal life – the silverware I used, the utensils my mother and

grandmother still used.”

Seeing ethnic cultures behind a cabinet is not strange to anyone

exposed to occidental culture for a long time, but for an educated

Mapuche woman who didn’t separate her culture and spirituality

from her cohabitation with the rest of Chilean territory, it was

weird. Imagine seeing objects of your ordinary life in a museum

exhibition, as if your culture was a dead one, uncivilized and rudi-

mentary. After working there for a while, Juana Paillalef earned a

scholarship to study for a Master’s in Intercultural and Bilingual

Education at the University of San Simón in Cochabamba,

Bolivia. In 2001 she became the director of the Mapuche Museum

of Cañete, in those days called the Museo Foclórico Araucano

Juan Antonio Rios Morales. She arrived in Cañete in the New

Year – “not the huinca new year, the Mapuche one in June.”

There, she saw the state of the museum and noticed that it didn’t

have a clear script or message. She thought that the best way to

improve it was by opening it to the people.

Sara Carrasco Chicahual works at the Regional Archive of

Araucanía. When you ask her to describe her trajectory, she

speaks in mapuzugun. After that, she translates. She is part

of the Gabriel Chicahual Mapuche community and Gabriel

Chicahual was her great-grandfather. She studied physical

education and worked as a volunteer at the Regional Museum

of Araucanía before becoming part of the professional team.

She earned a scholarship provided by the Ford Foundation and

got a Master’s degree in Education and Educative Community

with a thesis about intercultural education at Universidad de

Chile. After that, she became a professional at the archive: “As

Mapuche people we also have presence in the public services.

We can be public servants and be inserted in our culture.” In

fact, her development in both cultures is the added value of

the service. The archive is a living example of interculturality.

It shares space with the General Archive of Indigenous Affairs

of CONADI (the National Commission of Indigenous Affairs).

Both receive a lot of people from rural communities looking

for documents that allow them to understand their past and

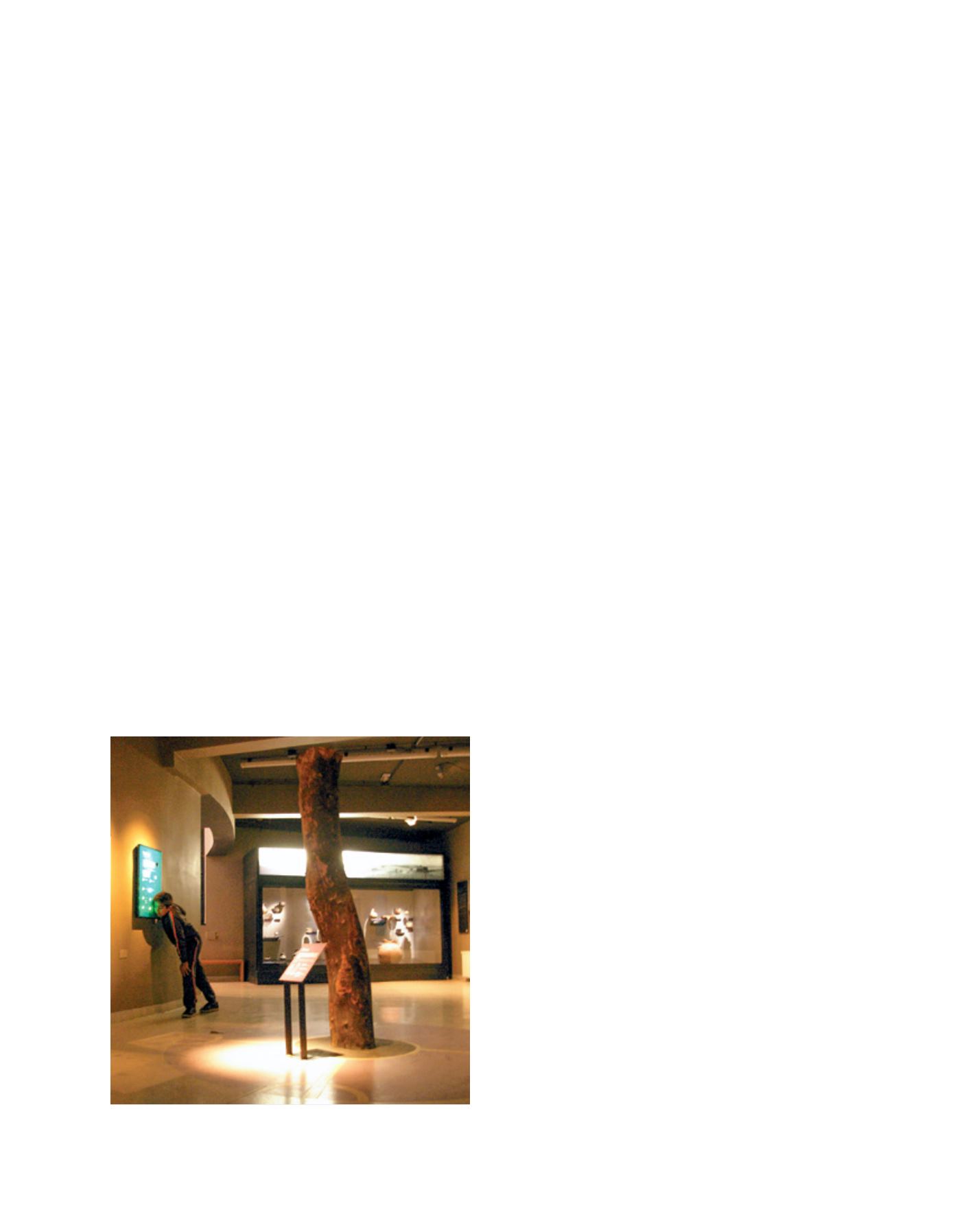

Local communities wanted people to know their language. Songs,

conversations and poems can be heard in the museum’s rooms

Image: Carolina Pérez Dattari

A

gree

to

D

iffer