[

] 71

Antonio Ríos, who was a Chilean president of the Radical Party

between 1942 and 1946. Many of the

kimches

told how the

land where the museum was erected once belonged to Lonko

Juan Cayupi Huachicura and was taken by the family of Juan

Antonio Ríos. This request involved a law for changing the

museum’s name, which took almost eight years to accomplish.

Juana Paillalef explains that the concept of a ‘museum’ does not

exist in Mapuche culture, so a long period of discussion with

the communities was needed to arrive at a concept. Today, the

museum is called Ruka Kimvn Taiñ Volil, which means ‘the

house that safeguards our roots’. In addition, the name Juan

Antonio Ríos was replaced with Juan Cayupi Huechicura. This

vindicatory act through language is elemental to understanding

the path the museum took.

A year after Juana Paillalef assumed the directory of the

museum, and after the participative strategic planning process

ended, the museum changed its mission to: ‘Promote and stim-

ulate la positive valoration of knowledge and thought towards

mapuche culture in the national society’. After this process,

the museum also started to elaborate a new script. Mapuche

poet Lionel Lienlaf was responsible for achieving this and he

faced a very important question: why have a museum if the

Mapuche culture is a living culture? Leonel Lienlaf worked

around the museum’s objects not as “the empty remains of

the past but as the continuity of memory”, as he mentions in a

text written for

Museos

magazine in 2010. That is why objects

in the museum are not only explained from a historical point

of view, they are also described with personal tales of what

the object means for a Mapuche person. Therefore, history is

built and rebuilt constantly.

Juana Paillalef describes the process with genuine admira-

tion. She recalls that the script process triggered a memory

recovery in many people of Mapuche communities. She thinks

that the Chilean domination over Mapuche people and, conse-

quently, the delegitimization of their culture, made them

hide and therefore forget their own stories and history. In an

adversarial context, were many people yet consider Mapuche

culture savage, the space of the museum breaks the colonial

domination over the hegemonic discourse of Chilean history.

In a territory still in conflict because of the territorial problem,

the museum, dependent on the Directorate of Libraries,

Archives and Museums of the Ministry of Education, is a rare

example of ethnic, religious and linguistic inclusion.

Currently, the museum sits in a territory of nine hectares,

were people can also visit or use a palin court (a typical

mapuche sport similar to hockey), a space for mapuche

rituals that hosts the We Tripantu (Mapuche New Year’s eve)

each year and Council of Lonkos activities, among others.

There is also an originary ruka (house), which is managed by

local communities. The museum itself has five rooms whose

topics were decided by the communities: ‘Life in the terri-

tory’, ‘How people live’, ‘Diverse manifestations of life’, ‘Living

with the earth’ and ‘The seeking journey’. Each room contains

informative audios in mapuzugun, Spanish and English, and

sign language, in addition to the voices of Mapuche men and

women that are heard in the background of the building. The

communities also decided to remove objects that, because of

their sacred quality, could not be held inside the building.

Both Sara Carrasco Chicahual and Juana Paillalef Curinao

are clear examples of a more participative way of functioning in

public services. The concepts of building, collection and public

are being removed to make room for concepts of territory, patri-

mony and community – concepts that reinforce the idea of

cultural and patrimonial spaces as real communication vessels

between the past and a more promising future where hegemonic

and colonial discourses and behaviours are overcome.

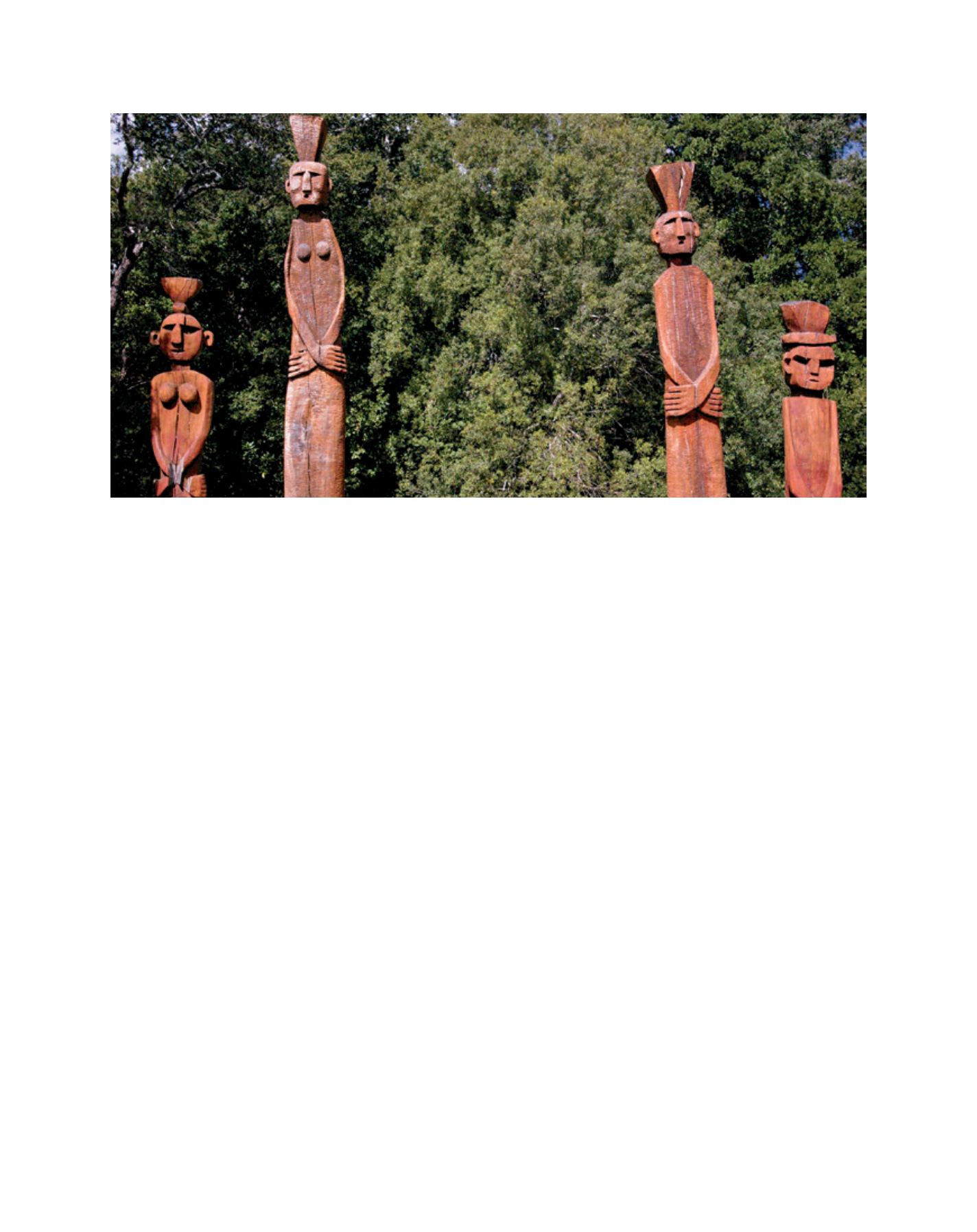

The four fathers of the Mapuche represented in Cerro Ñielol: Kuzezomo (the grand old woman), Fuchawencxu (the grand old man), Vllcazomo (the young woman)

and Wecewenxu (the young man)

Image: Carolina Pérez Dattari

A

gree

to

D

iffer