[

] 70

Image: Carolina Pérez Dattari

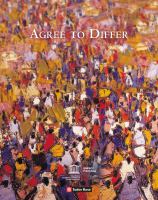

An originary ruka, which is managed by local communities inside the museum’s

grounds. Dominica Quilapi is a local knitter who is currently managing the ruka

the relation their families had with the lands in the region. In

fact, the whole register of the communities’ original names can

be found in the archive. “When they come, we greet them in

our own language; we receive them as owners of this space.”

The Archive also receives a lot of visits from settlers. They

mainly search for the first documents of their families and make

searches related to the territory.

After becoming director of the museum, Juana Paillalef

decided to start a participative strategic planning process in

which she and the museum’s other five workers achieve extraor-

dinary work. They invited Mapuche’s local communities,

ñañas

(women),

kimches

(wise men/women),

lamuen

(educators),

political leaders, the museums regional network, educational

communities (parents, student representatives, educational

authorities), artisans, and everybody who thought they could

contribute to the museum. She pulled off this process with the

help of the museum’s Friends Corporation, which helped to

perform a participative methodology in order to change the

museum’s mission and vision. “I went house by house to the

Mapuche communities because that’s the way to invite people

here. I decided to work from who I am– a Mapuche women –

so I invited within Mapuche’s parameters. First, I said to myself

‘I can visit three communities in one day’, but I barely finished

one a day. You have to equate the public services to the cultural

timetables. No community receives you in the afternoon, for

example. You have to respect the rituality of life.”

In this participative process, the museum invited multiple

actors to get involved with the museum, to expose their dreams

and ideas around this cultural space provided by the public

service of the State of Chile. Many of the people invited did not

even know there was a Mapuche museum in Cañete. Juana tells

of an experience when she arrived in Cañete: “One day I was on

the bus, and I was talking to a Mapuche man. I told him I was

going to the museum, and he told me: ‘I always asked myself

which

futre

(colloquial: wealthy men) that house belonged to.’”

The participative strategic planning process lasted a year. It

was guided by the conception of the museum as a community

space were the patrimony is alive and where the historic sense

is permanently being actualized. The change of museographic

perspective can be seen in the relations the process estab-

lished, making the collections interact with the patrimony,

where the communities and the territory were indispensable

in giving the museum an anti-colonialist perspective, and

where historic facts were told by ‘the south side of the Biobío

river’, by the people of Wallmapu.

Sara Carrasco Chicahual describes her role in the museum as

one connected with the citizens. The Association of Mapuche

Investigation and Development is working with Sara in

language workshops, were they teach mapuzugun to children

and adults. They also organize events related to book publica-

tions about Mapuche culture, among other things. They don’t

teach their language in the occidental way; they climb Cerro

Ñielol, a hill that was once used by Mapuche for ceremo-

nial acts, and there they practice their language watching the

natural surroundings. During 2014, the archive also hosted

the southern zone gathering of indigenous women organized

by SERNAM (the National Women’s Service), with the aim

of listening to opinions about a new Ministry of Women in

Chile. The gathering was in Cerro Ñielol, and the archive was

in charge of giving the whole activity the Mapuche protocol.

The first request Mapuche’s communities made to Juana

Paillalef after the participative strategic planning process was to

change the museum’s name. The original one, Museo Foclórico

Araucano Juan Antonio Ríos Morales, referred to the race in the

way conquerors did, not in the way they referred to themselves.

On the other hand, the name of the museum honoured Juan

The Wallmapu flag and the flag of Chile at the front of the museum

Image: Carolina Pérez Dattari

A

gree

to

D

iffer