The third monitoring round Lanzarote Committee Implementation Report (2023-25): A survey of the international legal framework protecting children against sexual abuse in the “circle of trust”, Italy emerges among the best-equipped states

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Criminalisation of sexual abuse in the circle of trust

- Protecting child victims of sexual abuse within the family

- Addressing harmful sexual behaviours by children

- Initiating investigations and prosecution

- Protecting child victims during investigations and criminal court proceedings

- Other safeguards for victims and third parties

- Measures following criminal proceedings

- Conclusion

Introduction

On 3 July 2025, the Lanzarote Committee adopted the report Protecting Children against Sexual Abuse in the Circle of Trust, dedicated to an analysis of the legal frameworks of the states parties to the Lanzarote Convention.

The Lanzarote Committee, that is, the Committee of the Parties to the Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse is the ad hoc body established by the Council of Europe’s Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse of 2007 (Lanzarote Convention) to monitor the respect and implementation of the Lanzarote Convention by State Parties. Specifically, the Committee is responsible for assessing the situation of the protection of children from sexual violence at the national level, stemming from information and data provided by the national authorities and other sources.

The Committee is composed of representatives of the 48 Parties to the Convention, and by participants and observers who regularly meet in plenary sessions.

Together with the monitoring procedure, the Committee also adopts opinions, thematic and topical statements, and contributes to the work of other international organisations.

In this report, the Committee assesses the protection of children within their “circle of trust”, that is, in the family and extrafamily environment where children live, in the 48 State Parties to the Convention, and is the result of the third monitoring round (2023-2025). Indeed, most cases of child sexual abuse are perpetrated by someone the child knows and trusts, including members of the extended family, persons with care-taking functions or individuals with whom the child frequently interacts in a trustworthy environment. Specifically, this report analyzes how Parties criminalise child sexual abuse committed within the circle of trust and the protection of children before, during, and after criminal proceedings. Furthermore, the report focuses on specific measures taken in response to cases of intrafamilial abuse, and how States address harmful sexual behaviour by children themselves.

The report highlights the progress made since the first monitoring round (2012-2018), mainly in regards to procedural safeguards for victims during criminal investigations and proceedings. However, significant gaps still persist in the criminalisation of sexual abuse of any child, in the absence of coercion, threat or force.

Criminalisation of sexual abuse in the circle of trust

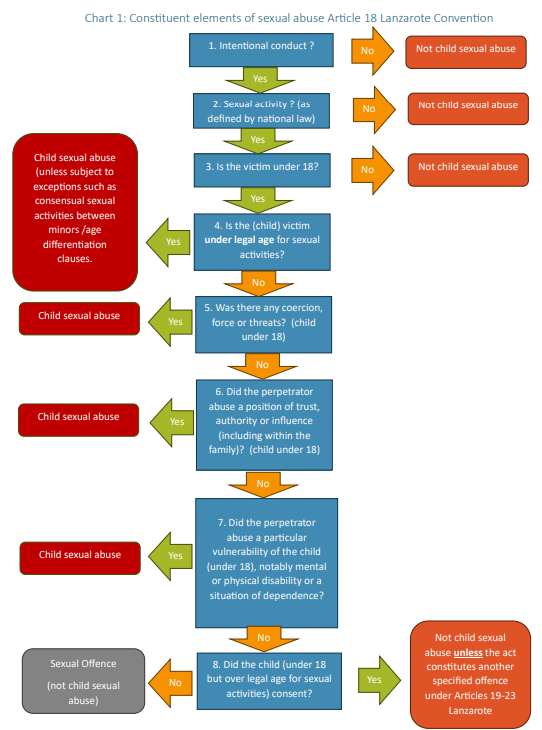

Articles 18 on sexual abuse and 27 on sanctions and measures of the Lanzarote Convention state that Parties must ensure the effective prosecution of child sexual abuse through the criminalisation of such conduct in a clear and foreseeable manner, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Convention. While the term “circle of trust” cannot be found in the provisions above, this term was used in the first and third monitoring rounds in order to facilitate the reference to a child’s relationship with persons in a “recognised position of trust, authority or influence over the child”. In this specific report, the attention was on situations falling under article 18, paragraph 1.b, second indent, where “abuse is made of a recognised position of trust, authority or influence over the child, including within the family”. In these circumstances, the Convention does not require the use of coercion, force, or threats for such activities to be considered a criminal offence. Furthermore, article 18 does not require the perpetrator to be an adult.

Criminalisation of sexual abuse of children of all ages by persons in a recognised position of trust, authority or influence

Italy is one of the 12 Parties out of the total of 48 to have a clear reference to “a [recognised] position of trust, authority or influence” in its criminal law provisions regarding sexual offences against children. Indeed, the Italian criminal code, Article 609-quater, prescribes “Sexual activity with a child carried out with abuse of trust, authority or influence over the child by reason of one's status or the office held or family, domestic, work, cohabitation or hospitality relationships”, regardless of their sex and/or sexual orientation or that of the perpetrator.

Regarding the specific topic of legislative provisions applicable to children below and above the legal age for sexual activities, the Report states that 38 out of 48 Parties have legislative provisions criminalising sexual activity with a child involving the abuse of a position of trust, authority or influence. Out of these 38, 21 Parties cover all situations of abuse and protect children of all ages, while 17 states Parties have legislative provisions applicable to children both below and above the legal age for sexual activities, but condition the crime to a list of circumstances and situations, potentially leaving children without sufficient protection.

Criminalisation of sexual intercourse or equivalent actions

- Criminalisation of sexual activities involving penetration

All 48 Parties criminalise sexual activities involving penetration where the victim is a child under the legal age for sexual activities. This situation is commonly criminalised under the terms of “rape” or “rape of a minor”. In these cases, it is not required for it to be proven that the child did not consent or that the perpetrator used violence, threat or force. These specifics can be used as aggravating circumstances, as established by Article 28 of the Convention.

If the child is over the legal age for sexual activities, sexual intercourse is a crime if the perpetrator abuses a recognised position of trust, authority or influence, or uses violence, threat or force. Also in these cases, the child’s consent or lack of consent is irrelevant.

- Criminalisation of sexual activities without penetration, but involving some physical contact

All 48 Parties criminalise sexual acts non involving penetration, such as sexual touching and molestation, where the child is under the legal age for sexual activities. Where the child is over the legal age for sexual activities, sexual activities not involving penetration (such as sexual touching) by a person in a recognised position of trust, authority or influence appear to be criminalised without any need to prove violence, threat, coercion or lack of consent in 42 out of 48 Parties, including Italy.

- Criminalisation of sexual activities not involving physical contact

The Convention requires Parties to criminalise all forms of sexual exploitation and abuse, including situations where no physical contact in involved, such as participating in a “pornographic performance” (Article 21), intentionally causing a child under the legal age for sexual activities to witness sexual activities (Article 22), and soliciting a child under the legal age for sexual activities for sexual purposes (Article 23).

Italy is amongst the 27 Parties having criminalised such conducts, and one of the 43 Parties to have criminalised the solicitation of a child where sexual abuse is committed online.

Protecting child victims of sexual abuse within the family

Exploratory interviews concerning possible sexual abuse in the family

Article 30 of the Convention calls for the best interests of the child and the rights of the child to be prioritised in carrying out investigations and criminal proceedings. In this regard, analysing the modalities in which exploratory interviews concerning possible sexual abuse in the family take place is crucial. During the first monitoring round (2012-2018), the Committee invited Parties to interview the child without informing the parents/legal guardians in advance or acquiring their consent in cases in which there is a reasonable suspicion of sexual abuse in the circle of trust and there is a reason to believe that parents/guardians may prevent a child from coming forward (Recommendation 26).

Italy is among the States that require a priori parental or legal guardian consent for a child to be interviewed in their absence.

Removal of the alleged perpetrator and the child victim from the family home

Italy is amongst the 37 Parties providing for the legal possibility to remove a person from the family home who is alleged to have sexually abused a child living in the same home, in accordance with article 14 of the Convention. These measures are typically implemented in the form of protective orders and other similar measures issued, typically, in cases of domestic violence.

Withdrawal and suspension of parental rights and authority (also applicable to legal guardians)

In regard to Article 27 on sanctions and measures, Italy provides for the possibility to fully or partially suspend and withdraw parental rights or authority on the basis of pending criminal proceedings or a criminal conviction for sexual abuse of own child. While doing so undoubtedly contributes to the protection of the child, the Committee notes that this alone is insufficient. Indeed, even if a parent's parental rights or authority were suspended or withdrawn, the parent remains entitled to many legal decision-making rights in respect of a child, for instance, in matters concerning health, education, physical movement, property, and others. This allows the accused parent to be able to influence the child’s testimony and negatively impacts the child’s well-being.

The Committee considers it appropriate to adopt a case-by-case assessment based on the child’s best interests.

Special representatives

Considering the needs of children, especially the special needs of child victims, these should be considered in their journey throughout the criminal justice system. Starting from the moment the abuse is reported, during the investigation phase and in criminal proceedings, the principle of the best interest of the child must be taken into account at all times.

Since the first monitoring round, there has been significant progress concerning the appointment of a special representative for a child victim in case of a conflict of interest with the holder of parental authority. Indeed, currently, 46 out of 48 Parties provide for the possibility of appointing a special representative. Specifically, as of 2025, Italy is one of the 36 Parties ensuring that special representatives and guardians ad litem receive appropriate training and legal knowledge. They must hold undergraduate and graduate academic degrees relevant to child protection, including in social sciences, law and psychology, and a minimum of relevant work experience. Furthermore, Italy is one of the 23 Parties ensuring that the functions of a lawyer and guardian ad litem are not combined in one person, in line with paragraph 105 of the Explanatory Memorandum to the Guidelines, stating that “combining the functions of a lawyer and a guardian ad litem in one person should be avoided, because of the potential conflict of interests that may arise”. However, Italy does not ensure the appointment of special representatives and guardians ad litem free of charge. In this regard, in Recommendation 20, the Committee urges Italy to “Provide special representatives and guardians ad litem free of charge for the child victim”, in accordance with Article 31 on general measures of protection.

Addressing harmful sexual behaviours by children

Article 16, paragraph 3 of the Lanzarote Convention recognises that some children may display risky or harmful sexual behaviours, including toward other children. Specifically, this paragraph calls upon Parties to provide intervention programmes and measures that are adaptable to the developmental needs of the child, with the best interests of the child in mind.

Children under the age of criminal responsibility

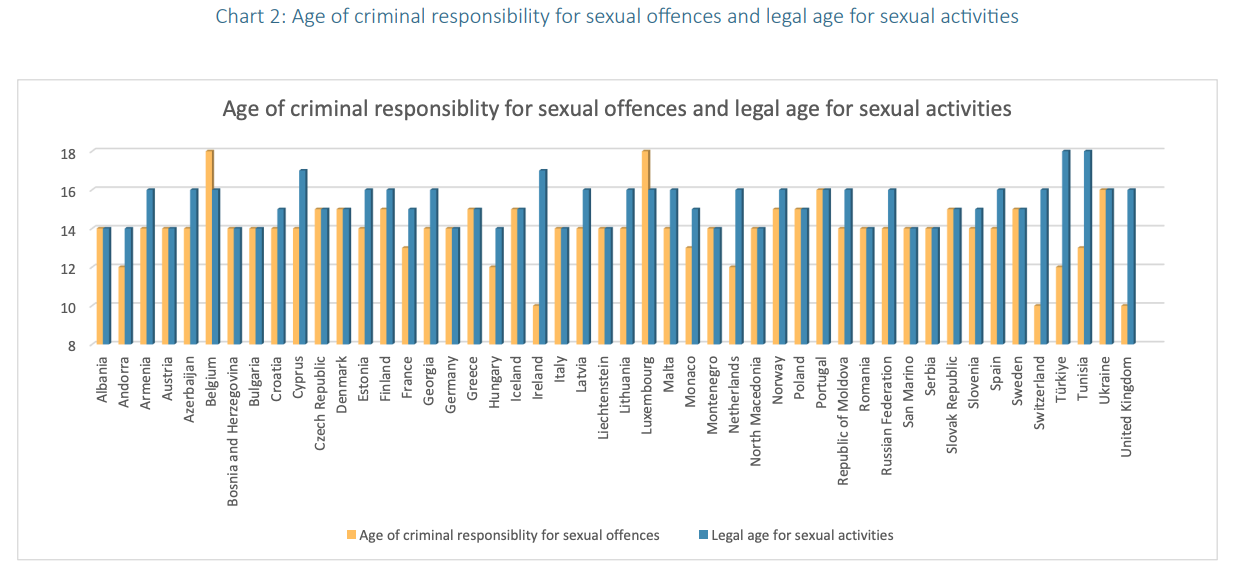

Regarding the age of criminal responsibility, the current monitoring round highlighted that Italy is one of the 36 Parties in which the criminal age is the same for all crimes. Specifically, Italy’s age of criminal responsibility is 14 years old, identical to the legal age for engaging in sexual activities. Italy is one of the 19 Parties in which the ages coincide.

In Italy, if a child, below the age of criminal responsibility, engages in harmful sexual behaviour with another child, educational projects must be set out under the direction and supervision of social services for re-educative and restorative purposes.

Children above the age of criminal responsibility

In sanctioning children above the age of criminal responsibility, different Parties take different measures. In Italy, for example, juvenile offenders may be sentenced to educational measures or community service, security measures or probation, detention or other forms of deprivation of liberty. However, children are subject to reduced criminal sanctions compared to adults. Italy presents promising practices, as its legislation provides for an individual assessment of a child's level of understanding and maturity before criminal proceedings can be brought against them. Furthermore, Italy pursues a restorative justice approach.

Initiating investigations and prosecution

Initiation and prosecution of investigations and proceedings in the absence of a complaint or in cases of withdrawal of a complaint

Article 32 of the Convention ensures that offences can be investigated and prosecuted regardless of whether a victim has filed a complaint or subsequently withdrawn one. This entails States taking a proactive and reactive approach to investigations, acting on information received from third parties, and ensuring the highest degree of protection for all children.

In Italy, proceedings may be initiated ex officio without the prior lodging of a complaint by the victim; they may also continue even if a victim withdraws their complaint. It is important to note, however, that these cases represent exceptions to the rule. Indeed in Italy, the general rule for sexual offences requires a complaint to be lodged by the victim. This general rule can be bypassed in cases of child sexual exploitation and sexual abuse. The Committee underlines that, where Parties provide for such exceptions, the relevant personnel must receive appropriate training to ensure they are fully aware of the exception and do not fail to apply it where necessary.

Hungary, Portugal, San Marino, and Türkiye do not provide for this exception and always require a complaint by the victim before investigations can proceed.

Italy is one of the 45 Parties allowing for investigations and prosecutions to continue even if a victim withdraws their complaint. It remains, however, within the prosecutor's discretion to terminate proceedings if no longer in the public interest. It remains unclear whether in this decision-making process the best interests of the child are taken into account. Indeed, recommendation 30 of the Committee states that “The Lanzarote Committee invites all Parties to ensure that the best interests of the child are taken into consideration when deciding whether to continue or cease proceedings for sexual offences against a child following the withdrawal of a complaint by the victim.”

Initiating investigations and prosecutions: Reporting in good faith

With regards to reporting suspicion of sexual exploitation or sexual abuse, the Report analyses how Parties ensure that professionals working in contact with children can report suspicion of sexual offences against children without risk of breaching confidentiality rules, and how they can encourage “any person”.

Italy specifically does not provide for legal obligations applicable to “everyone”; indeed, the legislation only imposes a general reporting duty on all persons who exercise public legislative, judicial or administrative functions or who are in charge of a public service. Italy ensures that certain professionals may face criminal or administrative sanctions if they fail to report sexual offences against children. Furthermore, Italy is one of the 18 Parties granting explicit waivers from confidentiality and professional secrecy rules for professionals reporting suspicion of sexual offences against children in good faith.

Concerning protections for any person reporting suspicion of sexual abuse, in Italy, persons who report suspicion of child sexual abuse cannot be held liable if the report is supported by a legitimate suspicion. In Recommendation 36, “The Lanzarote Committee invites all Parties to strengthen the protection of persons who report child sexual exploitation or sexual abuse in good faith and to keep the threshold for reporting suspicions as low as possible.”

Precautionary measures in respect of professionals and volunteers

In Italy, in line with Article 30 of the Lanzarote Convention, the suspected perpetrator can be temporarily suspended or removed from their professional or voluntary functions, pending the outcome of the criminal investigation or proceedings for sexual violence against a child. However, Italy is one of six Parties in which the mere suspicion of an offence is insufficient grounds to suspend a professional. Indeed, a prohibition on professional activities applies only upon conviction. The Committee in recommendation 37 requests “all Parties to allow for the possibility of removing the alleged perpetrator from the out of home care setting from the onset of the investigation.” Moreover, in Recommendation 38, “The Lanzarote Committee invites all Parties to consider introducing precautionary measures to suspend suspected perpetrators from professional or voluntary activities involving contact with children during criminal investigations and proceedings in relation to offences established in accordance with the Lanzarote Convention.”

Corporate liability

Italy holds legal persons liable for sexual offences, in accordance with article 26 of the Convention. Administrative fines, license revocation, and/or closure of the establishment are sanctions that may be imposed. Furthermore, the Committee praised in the Report Italy’s possible definitive disqualification of legal persons from carrying out specific activities.

Protecting child victims during investigations and criminal court proceedings

Support for child victims in the investigation phase

Article 30 paragraph 2 of the Convention aims to ensure the availability of procedural rules and safeguards during the collection of the child’s testimony, guaranteeing the best interests and rights of the child to avoid exacerbating the trauma that child victims have already suffered.

The Report then sheds light on Barnahus (children’s house)1 or Bernahus-type services in place in State Parties. All Parties have implemented measures to ensure that interviews of child victims are arranged in a child-friendly setting, and there seems to be a recognition of the need to make Barnahus or Barnahus-type services available to all children. Indeed, Italy is amongst the 24 Parties in which such services have already been set up or are in the process of expansion.

Furthermore, Italy ensures that all staff responsible for interviewing child victims are required to undergo suitable qualifying training, that such interviews be conducted as soon as possible after the offence, that the duration and/or number of interviews be limited, that such interviews take into account the child’s age and attention span, and, if possible, that the interviews be conducted by the same person who conducted the first one and under the same material conditions as the first. Lastly, Italy’s national legal framework offers criminal defence the possibility to contest a child’s disclosure during the interview through questions, thus obviating the need for the child to be present in the courtroom during the proceedings.

Use of video recording and /or live link technology to facilitate pre-constituted evidence

Article 35, paragraph 2 and Article 36, paragraph 2 require States Parties to facilitate the participation of children in judicial proceedings in a way that would ensure they are not re-victimised or re-traumatised. It is understood that facilitating the hearing or testimony of the child remotely or via pre-constituted video-recorded evidence is generally in the interests of the child.

While during the first monitoring round Italy, alongside Bulgaria, Malta, the Netherlands, Romania and San Marino, did not allow for child victims of sexual exploitation and sexual abuse to testify without being physically present, the current monitoring round shows that all parties have this possibility, proving that strong progress has been made over the years.

Significant progress has also been made by Italy, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia regarding the availability and use of video recording. Specifically, Italy is one of the 31 Parties confirming that video recording was used systematically or as a general rule for all children, and one of the 27 Parties in which pre-recorded/pre-constituted evidence is used in court, removing the need for the child victim to participate live in the criminal court, unless the court deems it necessary.

Avoiding contact between the victim and the accused during criminal proceedings

Article 31 on general measures of protection presents a non-exhaustive list of child-friendly procedures designed to protect children during proceedings, which should be applied both during the investigations and during trial proceedings, for example “ensuring that contact between victims and perpetrators within court and law enforcement agency premises is avoided, unless the competent authorities establish otherwise in the best interests of the child or when the investigations or proceedings require such contact.”

Italy is one of 39 Parties that have such measures in place.

Protecting the child’s right to privacy and personal data from disclosure in the media

The current monitoring round reports that Italy is amongst the 47 of the 48 Parties that allow the possibility of holding hearings in private without the presence of the public. Furthermore, Italy is also one of the 34 Parties with legal provisions in order to prevent disclosure of the child victim’s identity in the media.

Access to legal advice and legal representation

The Convention leaves it to the individual States Parties to determine whether to grant victims the right to be parties to criminal proceedings and does not create a blanket right to free legal aid, as the provision specifically refers to free legal aid “where warranted”.

Since the first monitoring round, Italy has guaranteed free legal aid or assistance to children. At the time, only 22 Parties provided for this;findings from the current monitoring round show that all 48 Parties provide some form of legal advice free of charge to child victims. Differences mainly concern whether this legal advice is provided by an association, a victim support office, or a legal aid lawyer or attorney. In Italy, a special curator may apply for legal aid on behalf of the child. Furthermore, Italy is one of the 35 Parties providing “legal aid lawyer” or attorney, either free of charge or under more lenient conditions than for adults.

Psychological assistance to child victims in investigative and judicial proceedings

Article 30, paragraph 2 and Chapter VII, generally dedicated to investigation and prosecution of child abuse, aim to protect children as victims and witnesses. Their vulnerability is taken into consideration; indeed, the Convention aims to avoid exacerbating the trauma which they have already endured. Amongst other things, this can include psychological assistance to child victims in investigative judicial proceedings to avoid secondary victimisation.

Italy is amongst the 20 Parties providing for a professional to accompany child victims throughout the proceedings, at both the investigative and the trial stage.

Other safeguards for victims and third parties

The Convention requires that Parties take a protective approach towards victims and those close to them. This is done to avoid unintended adverse consequences and secondary victimisation. Furthermore, it has been proven that the consequences of childhood sexual exploitation or abuse may well last into adulthood, underlining the need for therapeutic recovery for an undetermined period, including after the criminal proceedings are over.

Provision of therapeutic assistance to persons close to the victim

The first monitoring round (2012-2018) showed that Italy was amongst the 7 Parties having a legal framework in place providing support to persons close to the victim, in line with Article 14, paragraph 4 of the Convention. The current monitoring round shows that this number has increased significantly, reaching 41 out of the 48 Parties. Italy, in particular, offers psychological support.

Preventing secondary victimisation

As a result of a child victim’s disclosure of sexual exploitation or sexual abuse, the risk of adverse consequences or secondary victimisation can arise. In this regard, Parties to the Lanzarote Convention have installed legal safeguards to protect children by ensuring that professionals are equipped to receive a child’s disclosure even before any investigations or proceedings are underway. Italy, alongside France, Georgia and Luxembourg, provides for courts to issue emergency orders to safeguard the child or to suspend contact rights of parents. Italy also ensures the use of child-friendly procedures in general to address such risks.

Long term victim support

In addition to mainstream health, social, educational, or therapeutic services provided in the context of general health, education, or social services, Italy ensures that protection measures are decided by the guardianship judge or family courts, including as regards contact, visitation rights, parental authority, and residence.

Measures following criminal proceedings

Measures to monitor or supervise persons convicted of child sexual abuse

The Lanzarote Convention requires Parties to ensure that all sexual offences perpetrated against children are punished by effective, proportionate, and dissuasive sanctions, including deprivation of liberty (and extradition). The Convention further requires that Parties adopt other measures, such as monitoring and supervision of convicted persons, through DNA and identity record data. These measures often overlap with consensual intervention programmes and measures for convicted offenders, including programmes or measures accessible during the proceedings, multidisciplinary interventions, and assessments of dangerousness and possible risks of repeat offending.

During the first monitoring round, Italy was among the Parties having some form of prohibition or mandatory checks in place to prevent persons convicted of child exploitation and sexual abuse from working with children. To this day, Italy is one of the 33 Parties that have some form of prohibition on the exercise of professional activities requiring regular contact with children and on mandatory criminal record checks during recruitment procedures. Furthermore, Italy is one of the very few States providing psychological or risk assessments to offenders prior to release and continues to supervise released offenders through a relevant authority. Italy also allows convicted offenders to be subject to prohibitions or bans on entering certain localities, such as schools and playgrounds.

Sharing data on offenders convicted of child sexual abuse with other countries

Offenders may sexually abuse children in other countries. The Convention requires Parties to share data on convicted sexual offenders with other State Parties, in accordance with the rules applicable to international transfers of personal data. The Report underlines that the sharing of data and information is particularly helpful in various situations, such as screening potential employees or volunteers, during investigations of suspected child sexual exploitation or sexual abuse in the context of travel and tourism, during the prosecution phase and in the context of sentencing if previous convictions are considered an aggravating circumstance.

All Parties to the Lanzarote Convention, except Tunisia, have ratified the Council of Europe Convention on Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters (ETS 30), one of the 15 Council of Europe conventions on international co-operation in the criminal field.

The Convention on Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters specifically calls upon Parties to regularly exchange information with other Parties concerning nationals of that State Party.

Furthermore, all EU states are connected to the European Criminal Records Information System (ECRIS), allowing them to exchange information on convictions of EU nationals.

Lastly, the International Criminal Police Organisation (INTERPOL) also provides a platform for international police co-operation, enabling police in member countries to consult the INTERPOL notices database.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this third cycle of monitoring (2023-2025) showed that States Parties have made significant progress in legislating and reforming their criminal systems to meet the requirements and standards set out in the Lanzarote Convention. Italy has a fully compliant system to combat child sexual exploitation and abuse in force. The challenge of effectively implementing the normative framework in all circumstances remains, but the available legal tools look satisfactory.

1Barnahus is the Scandinavian word for “children’s house”. Barnahus works as a child-friendly office, under one roof, where law enforcement, criminal justice, child protective services, and medical and mental health workers cooperate and assess together the situation of the child and decide upon the follow-up.