[

] 21

Intercultural solidarity

among people in poverty

Diana Skelton, ATD Fourth World

O

vercoming persistent poverty fosters a sense of

belonging among people of different cultures,

social backgrounds, beliefs and religions. The

promise implicit in the Declaration of Human Rights has

long been denied for people in poverty, who are frequently

treated as less than human. Despite this, they often reach

out in solidarity to others who are different from them,

demonstrating a tremendous generosity of spirit. One of

our approaches to recognizing and increasing this solidar-

ity is the Fourth World People’s University, where people

in deep poverty and from other backgrounds, of many

ethnic origins, cultivate mutual understanding.

1

While we run this project in many countries, this article will

focus on France and Belgium. As these countries become more

diverse, native-born participants in the People’s University are

joined by immigrants from Algeria, Angola, Cameroon, the

Democratic Republic of the Congo, Germany, Guadeloupe,

Haiti, Mauritius, Morocco, Niger, the Republic of Cabo Verde,

the Republic of the Congo, Senegal, Serbia, Spain, Tunisia and

Viet Nam, as well as members of the itinerant Roma population.

ATD Fourth World’s founder, Joseph Wresinski, spoke in 1980

to people in poverty at a conference he organized about immigra-

tion: “Traps are set to prevent us from acting in solidarity. We are

crushed by overcrowding in underserved and run-down housing

projects. Worn out, we end up distrusting one another – even

preventing our children from playing together. We’re jealous of

the person who got a flat, the person who took our sanitation

job.” In this context of rising diversity, tension, and misunder-

standings, it can become harder to perform the everyday acts

that create fellowship in society. Yet, some people in poverty

use their own experience of hardship to reach out to people

of different ethnicities. One unemployed Belgian man related

during a People’s University that because bus riders make fun

of his clothes, he prefers to walk. Every day, he passes a North

African man whose job is sweeping the street. The Belgian said:

“I decided to greet him. But when I said, ‘hello’, he didn’t

answer. I could have done what some people do by blaming

foreigners for taking jobs that I wish I had. He didn’t even answer

me. But then I realized that sometimes I don’t feel like answering

my own children. Maybe the man is having a bad day. Maybe that

very morning, he learned that he would soon be out of work, or

was insulted by his boss. Or a passer-by was rude to him, so that’s

that. It happens to me too. When someone treats me that way, at

home I just can’t treat my kids well. They’re asking for attention,

and I don’t answer. So I won’t judge him for it.”

This father tried to connect with a neighbour, and then

worked to understand why his greeting remained unan-

swered. The harshness in his own life has led him to close

himself off sometimes too, but also to understand that others

do the same. By not judging the neighbour, he chooses to keep

open the possibility of connecting in the future.

Many people living in poverty also reach out to others by

providing them with material support despite their own daily

struggles and tense living conditions. It is striking that on any

given night in France, tens of thousands of homeless people are

taken in by friends who themselves struggle in overcrowded

conditions. By offering informal shelter, people incur risks:

sometimes violating their own rental agreements; struggling

to stretch meals; and adding stress to their own family rela-

tionships. And yet, many people offer this form of solidarity

because they know first-hand how hard it is to be homeless.

At the same time, despite frequent acts of solidarity, when life

is hard and everything is lacking, it can be particularly difficult

to summon up feelings of fellowship. Poverty hammers away

at people’s physical health. It limits possibilities of living in a

safe home, succeeding in school and finding decent work. In

addition, poverty erodes people’s relationships with their neigh-

bours and relatives, their freedom to express their thoughts and

their very sense of self. In the main train station of Brussels,

a non-profit organization has separated homeless people by

ethnicity for food distributions, giving priority to native-born

Belgians while there is no guarantee of enough for everyone.

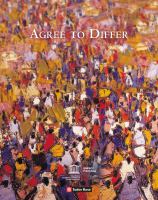

Image: ATD Fourth World

The Fourth World People’s University has been developed with people of all

cultural backgrounds living in persistent poverty

A

gree

to

D

iffer