[

] 82

hospitality in Hindu culture. Central to the Hindu

Dharma,

or Law, are the values of

karu

ṇ

ā

or compassion,

ah

iṃ

s

ā

or

non-violence towards all, and

seva

or the willingness to

serve the stranger and the unknown guest. Providing food

and shelter to a needy stranger was a traditional duty of the

householder and is practiced by many still. More broadly,

the concept of

Dharma

embodies the task to do one’s duty,

including an obligation to the community, which should

be carried out respecting values such as non-violence and

selfless service for the greater good.

The Tripitaka highlights the importance of cultivating four

states of mind:

mett

ā

(loving kindness),

mudit

ā

(sympathetic

joy),

upekkh

ā

(equanimity), and

karu

ṇ

ā

(compassion). There

are many different traditions of Buddhism, but the concept

of

karu

ṇ

ā

is a fundamental tenet in all of them. It embodies

the qualities of tolerance, non-discrimination, inclusion and

empathy for the suffering of others, mirroring the central

role which compassion plays in other religions.

The Torah makes 36 references to honouring the ‘stranger’.

The book of Leviticus contains one of the most prominent

tenets of the Jewish faith: “The stranger who resides with

you shall be to you as one of your citizens; you shall love

him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

(Leviticus 19:33-34). Further, the Torah provides that “You

shall not oppress the stranger, for you know the soul of the

stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of

Egypt” (Exodus 33:1).

In Matthew’s Gospel (32:32) we hear the call: “I was

hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave

me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed

me.” And in the Letter to the Hebrews (13:1-3) we read:

“Let mutual love continue. Do not neglect to show hospi-

tality to strangers, for by doing that some have entertained

angels without knowing it.”

When the Prophet Muhammad fled persecution in Mecca,

he sought refuge in Medina, where he was hospitably

welcomed. The Prophet’s

hijrah,

or migration, symbolizes

the movement from lands of oppression, and his hospitable

treatment embodies the Islamic model of refugee protec-

tion. The Holy Qur’an calls for the protection of the asylum

seeker, or

al-mustamin,

whether Muslim or non-Muslim,

whose safety is irrevocably guaranteed under the institution

of

Aman

(the provision of security and protection). As noted

in the Surat Al-Anfal: “Those who give asylum and aid are in

very truth the believers: for them is the forgiveness of sins

and a provision most generous” (8:43).

There are tens of millions of refugees and internally

displaced people in the world. Our faiths demand that we

remember we are all migrants on this earth, journeying

together in hope.

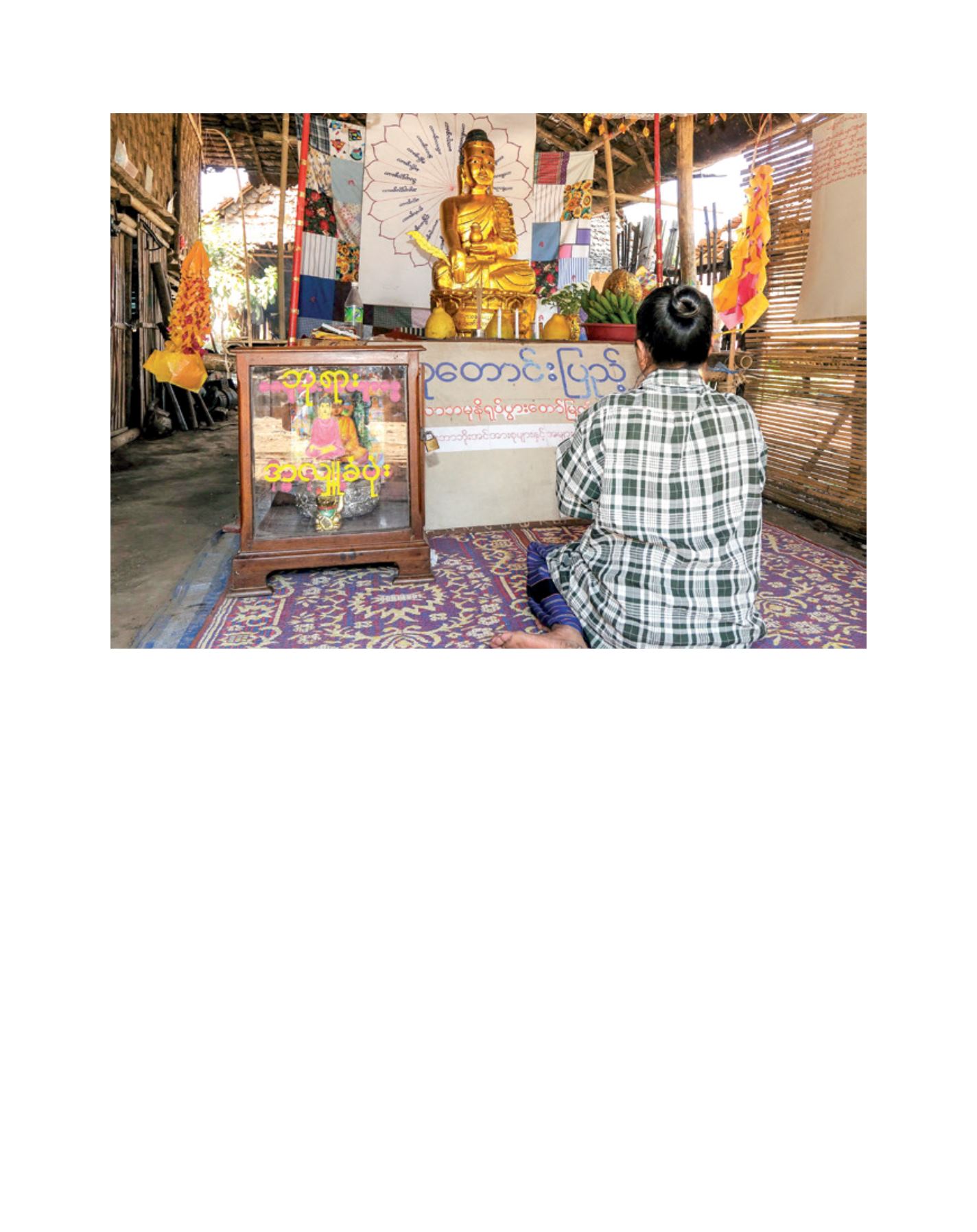

Image: UNHCR /R. Arnold

In Thailand, a refugee from Myanmar prays in Nu Po Refugee Camp

A

gree

to

D

iffer