[

] 85

sion and ridicule, but to enable it to shine. The youth that have

led the movements for justice and liberation in the past years

are exactly these kinds of people, working together as Muslims,

Jews and Christians for justice and the liberation of all people.

There are some practical steps that need to be taken to bring

interfaith awareness to educational encounters. We need to

develop all of our curricula – and not just religious studies – to

cater to living in a world of difference by equipping teachers

with the necessary skills to read these texts and bring to bear

real-world examples of living in communities of multiple faiths.

Moreover, we need to engage in research and collaborative

projects for the common good of communities of multiple faiths.

Debating dialogue

The following prescription of identity is attributed to the

Hasidic rabbi Menachem Mendel (1787-1859):

If I am I because I am I,

and you are you because you are you,

then I am I

and you are you.

But if I am I because you are you

and you are you because I am I,

then I am not I

and you are not you!

The suggestion here is that our sense of self – our sense of

who we are – cannot come from any mockery or putting

down of others. We see that suggestion again in the verse from

the Qur’an that reminds Muslims of the caution from God:

“O you who believe! Let not a people deride another people.

Perhaps they are better!”

3

In interfaith communication, disparagement and a sense of supe-

riority would be sure-fire guarantees of failure. Our sincerely held

faiths are of vital importance to each of us because they direct

us to the essence of who we are and what we are about. Vitally

important, too, is the desire we each have to follow truthfully

in our faith. This is not to be mocked. But there are many who

have cautioned as to possible dangers. Writing with a dry sense

of humour in his novel

Lake Wobegon Days,

Garrison Keillor

described communities of people who dissected teachings, each

sect striving to be purer and purer adherents, until “having tasted

the awful comfort of being correct” they could look down on

those who had not reached that state. There are, though, power-

ful goals for all to strive for and these direct us beyond that kind

of complacency. Thomas Merton was an American Catholic and

a Trappist monk. He spoke of “the mystery of the freedom of

divine mercy which alone is truly serious.”

An important part of interfaith understanding is renew-

ing our joint achievements from the past. Our ancestors have

achieved much in the past in being able to create the infrastruc-

ture of our faiths based on mutual learning. In the medieval

period they have been open in learning from the experiences

of each other’s faiths. These achievements surely need to be

celebrated and acknowledged in any new interaction that takes

place today – for example the spirit of

convivencia

that was

achieved in Islamic Spain and the removal of

dhimmi

status for

the Jews of Yemen based on a saying of the prophet of Islam in

what is called by Muslims

Israiliyat

literature.

4

The important point is to remember that there are parallels

in religions both in time and space. We can call this approach

of finding parallels ‘transversal fractals’. This would denote the

similarities across time and in the present experience of lived

religion between religions like Islam, Judaism and Christianity.

As the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Rowan

Williams advises, we should compare like with like in each

religion and should not ‘compare apples and oranges’. We

compare the best manifestation and expression with each other

in dialogue. And likewise we would like to suggest extending

from the Archbishop’s advice that we make spaces available for

debate to take place between those of religious attitudes that

would like to emphasize differences in a more critical debate

paradigm in order to convert the other. Without looking down

upon the people of mission and debate among our co-religionists,

and without a sense of superiority in relation to them, we provide

them space for expressing their strongly held convictions. After

all, religion is about convictions. Convictions can be historicized

by some of us but others rather choose to live in the present of

convictions, and that attitude of religiosity has as much if not

more of a right for expression than those of us who prefer to

historicize our convictions and hence relativize them. It can only

lead to mutual enrichment across faith boundaries if we are able

to make space for the expression of our religious compatriots as

well as those of other religious adherents.

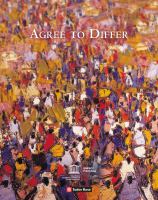

The interfaith community at large wholeheartedly welcomes

this United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization publication of

Agree to Differ

to celebrate the

International Decade for the Rapprochement of Cultures (2013-

2022). We hope that our support in this timely effort is received

and recognized as a collective voice of the faith communities

around the world that stand for peace, understanding and justice.

Advancing Religious Freedom

This report was written in collaboration with interfaith scholars from

different religious traditions from around the world. It documents the

discussions that took place at the Istanbul Process Meeting 2014 at

Doha to discuss the implementation of UNHRC Resolution 16/18.

It was a rare gathering hosted by DICID, consisting of interfaith

practitioners with representatives from UN institutions. An attempt was

made to develop a common vocabulary about “Religious Freedoms”

based on diverse institutional, cultural and religious experiences.

Image: DICID

A

gree

to

D

iffer