[

] 90

standing and even conflict. Luckily for us, this is not the case

in Singapore.

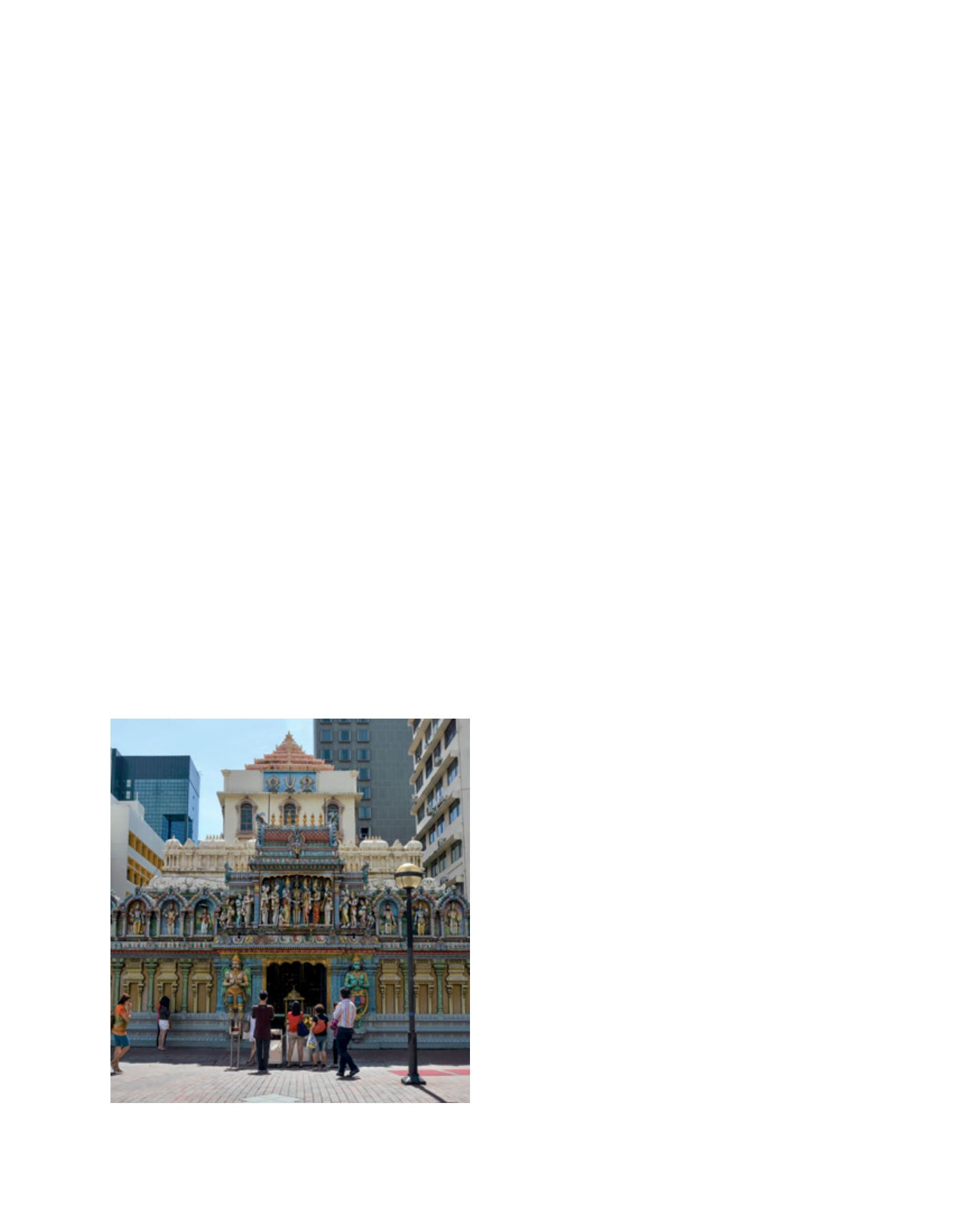

I often take visitors from abroad to join me in a walking

tour of Waterloo Street. On this street, we have a Jewish syna-

gogue, a Hindu temple and a Buddhist temple dedicated to the

Goddess of Mercy, Kuan Yin. My foreign friends are amazed

at the sight of Buddhists worshipping at the Hindu temple

and vice versa. I tell them that this is one of the miracles of

Singapore.

However, relations between the followers of the different

religions in Singapore have not always been amicable. In 1950,

riots occurred for several days when an insensitive British

judge ordered that a Dutch girl, Maria Hertogh, be remanded

in a Catholic convent, pending his ruling on whether custody

should be awarded to Maria’s biological mother or her Malay

foster mother who had raised her.

In 1964, a procession to celebrate the Prophet Muhammad’s

birthday was attacked by Chinese gangsters. This led to several

days of rioting, arson and mayhem.

The memories of those riots, as well as the one which

occurred on 13 May 1969, will never be forgotten. They have

motivated Singaporeans to work hard to prevent the recur-

rence of such unhappy events.

Singapore’s state of religious harmony did not happen by

chance. We got here from crafting important policies, laws

and institutions which helped to promote religious harmony

in the country.

Secularism, Singapore style

First, Singapore is a secular state. We do not have a state reli-

gion, unlike Malaysia or the United Kingdom. The state does

not promote religion. It is, however, not hostile to religion,

unlike the communist countries.

Second, Article 15 of the Singapore Constitution guar-

antees freedom of religion and the right to propagate one’s

religion. The Court of Appeal has held that it is not illegal for

a Singapore citizen to be a Jehovah’s Witness, a proscribed

group. He is, however, not exempted from being called up

to serve his national service. In another case, the same court

held that a citizen working in an educational institution is not

exempted from singing the National Anthem or reciting the

National Pledge on account of his religious beliefs. In other

words, in Singapore, a citizen’s right to religious freedom is

subordinated to the public good.

Third, in Singapore the right to free speech is not an abso-

lute right. The Penal Code makes it an offence to utter words

which deliberately wound the religious feeling of others.

The Sedition Act makes it an offence to promote feelings of

ill will or hostility between different races or classes of the

population. In 2005, three bloggers were convicted under the

Sedition Act for posting web-blog comments that were anti-

Muslim. In Singapore, unlike Denmark and France, cartoons

which depict the Prophet Muhammad would be deemed to be

offensive, punishable under both the Penal Code and Sedition

Act and not protected by the freedom of speech.

Fourth, in 1990 the Singapore Parliament enacted the

Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act. The law established

the Presidential Council for Religious Harmony, a body

consisting of both religious and lay leaders, to advise the

President on matters affecting religious harmony.

The law also empowers the Government to issue restraining

orders against preachers who threaten our religious harmony.

A few years ago, a good friend who is a pastor in an independ-

ent Protestant church sought my advice. He told me that he

had received a letter from the Government warning him that

he would be stopped from preaching unless he refrained from

attacking the Catholic church in his sermons.

I asked him to show me the text of his recent sermons.

After reading them, I told my friend that I agreed with the

Government’s warning and that he should stop his unwar-

ranted attacks on the Catholic church.

I remember that a few years ago, a Christian pastor was

caught on film badmouthing the Buddhists and Taoists. The

video went viral and the public response was unanimous. He

had crossed the line and should apologize. The pastor did apol-

ogize and the Buddhists and Taoists decided to forgive him.

Fifth, I believe that the IRO has played a very positive role

in the maintenance of religious harmony in Singapore. IRO’s

members belong to 10 different faiths. They serve in their

individual capacities and not as the official representatives

of their respective religions. The fact that they get along

well, respect one another’s faith, visit one another’s places of

worship and appear together at public performances of joint

religious prayers is an inspiration to the community. They set

a good example for others to follow.

In conclusion, I would reiterate my point that religious

harmony is one of Singapore’s most important achievements of

the past 50 years. Our success is due partly to our policies, laws

and institutions. It is also due to the good sense of the people

of Singapore. Singaporeans have developed the cultural DNA to

respect one another’s faiths. It is un-Singaporean to insult, dispar-

age or make fun of the deities or religious beliefs of others.

The Sri Krishnan Temple on Waterloo Street, Singapore, where several

places of worship of different religions coexist in peaceful proximity

Image: Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth

A

gree

to

D

iffer