© Università degli Studi di Padova - Credits: HCE Web agency

- HUMAN RIGHTS CENTRE

- RESEARCH AND COURSES

- Publications

- Archive "Peace Human Rights"

- HUMAN RIGHTS CENTRE

- RESEARCH AND COURSES

- Publications

- Archive "Peace Human Rights"

Serena Salviato holds a master's degree in Human Rights and Multi-level Governance from the University of Padova. This In Focus article is an excerpt from his master thesis, discussed in March 2020 under the supervision of prof. Lorenzo Menchi.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The United States’ ties to Chile in the first and most repressive phase of the Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship, from 1973 to 1981, represent a complex and controversial history for the U.S. In this seven-year period major human rights violations were registered in Chile as the American administrations of Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter entertained a relationship with General Pinochet.

To reconstruct the diplomatic connection that each administration maintained with the Dictator and to understand the degree of influence that the human rights aspect had on the formulation of the U.S. foreign policy towards Chile, a factual understanding of the matter is provided in this article. The evidentiary base of the Chile-U.S. relationship is offered by the investigation of the primary sources, i.e. the voluminous U.S. communications collected during the period under scrutiny. These sources are accessible because of the “Chile Declassification Project” carried out by the Clinton Administration. The project resulted in 1999/2000, in the release of an extremely substantial amount of formerly classified and previously unavailable documents - almost 23,000 files - covering the relation of the two countries from 1968 to 1991- though part of the vast U.S. archives remains secret. The “United States National Security Archive” and the “Foreign Relations of the United States” are two online sources offering collections of the original historic U.S. documents, including collections covering the key issues and episodes of the time and subject under discussion in this article. Particularly important and revealing are the intelligence reports referring information from sources inside the Pinochet regime and cables and calls from the U.S. Embassy in Santiago, the memoranda of conversations recording the private communications and meetings of Nixon, Ford and Carter with their highest national security advisers as well as the exchanges of government agencies of the U.S; the latter include the State Department, the National Security Council, the Defense and Justice Departments, the Congress, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

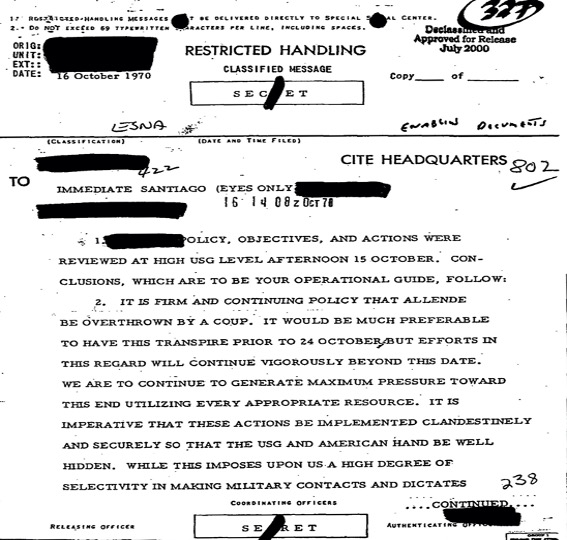

In the years immediately preceding the Chilean dictatorship, the secret communications of the then American National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, with President Nixon, his staff and the CIA testified to the Cold War political context of the time. The Chile-United States relation was marked by the American imperative to not allow communism spread in the Western Hemisphere and to preserve the economic interests - mainly related to copper industries - they had in Chile. Consequently, since the early 1960s, a combination of the U.S. political/ideological and economic interests prompted different attempts to influence Chile’s political direction through a series of covert operations. Specifically, the main efforts were made against the socialist leader Salvador Allende, whose election would have undermined American interests. In this context, Nixon authorised a CIA two-track covert operation to prevent his election. Once this failed, he found it necessary to covertly authorise the Agency to create “the conditions as great as possible” to overthrow Allende’s duly elected Popular Unity government. Nixon commented that Allende’s government was not acceptable in Chile.

Document 1: United States Central Intelligence Agency, Policy to overthrow Salvador Allende by Coup, 16 October 1970.

On 11 September 1973, the Chilean President was overthrown, and the military Junta guided by Pinochet was installed.

The ideological and economic reasons behind the United States’ attempts to influence Chiles’s political course in the 60s and the early 70s were the same as those behind the satisfaction of the Nixon administration for the violent military takeover. The main idea conveyed by the declassified records taken into consideration was that the White House was very pleased about the Junta since it represented the end of the socialist experiment in Chile. It was not perceived as a threat to American interests but a natural ally. Publicly the United States opted to display neutrality towards the military and avoided an immediate recognition of the Junta; however, the communications with Santiago attested a diametrically opposed reality: Washington expressed a warm welcome privately to Pinochet, offering assistance “in any appropriate way” for its consolidation (See Document 2).

Document 2: United States Department of State, United States Government - Attitude Toward Junta, 13 September 1973.

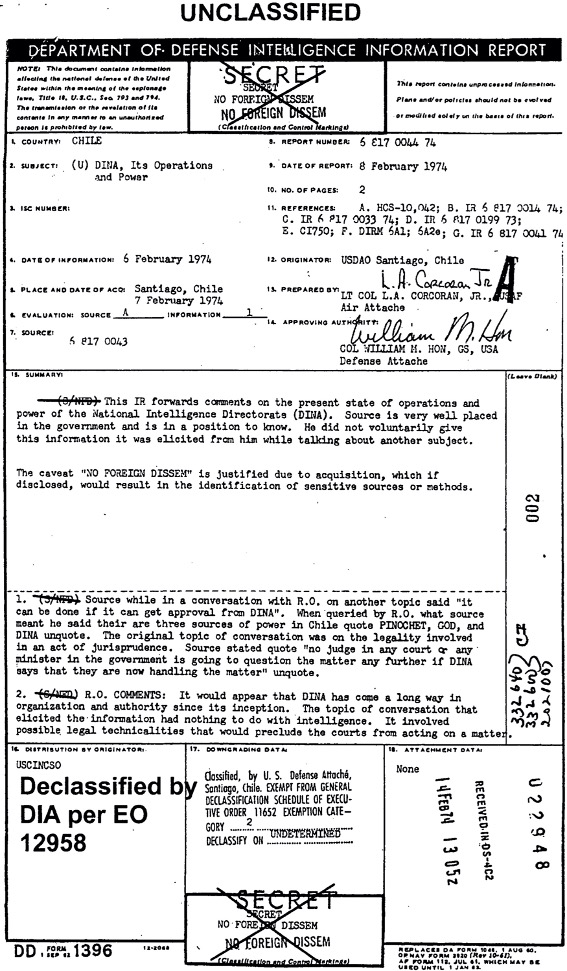

However, from the early days, it was apparent that the U.S. was going to be dealing with an oppressive and brutal dictatorship regime: cables of CIA and Embassy from Santiago to Washington had immediately documented the climate of terror characterising the post-coup months. The State Department was informed that, upon arrogating the rule over the Nation, the Junta began to build authority by constructing a repressive apparatus, including declaring the state of war, issuing a series of measures restricting people’s basic freedoms, and carrying out an anti-Marxist Campaign through arbitrary detentions, summary executions and disappearances. The CIA soon commented that there were three sources of power in Chile “Pinochet, God, and DINA”. As detailed in the intelligence reports, the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA) was Pinochet’s “Gestapo-like” secret police which, under the direction of Col. Manuel Contreras, who directly responded to Pinochet, established a network of secret detention centres throughout Chile. In these places, detainees experienced horrific methods of torture.

Document 3: United States Embassy Chile, DINA, its Operations and Power, 08 February 1974.

The attitude of the Nixon-Kissinger administration and that of the subsequent Ford-Kissinger to these human rights violations was quite identical: both, while formulating executive decisions towards Chile, considered strengthening ties with the military as their main objective. To this regard, in a meeting of U.S. officials, it was suggested, in response to the mounting internal criticism towards a U.S. foreign policy sustaining such a regime, that however unpleasantly the Junta acted, was still better for the U.S than Allende’s government had been. The knowledge of the Chilean horror did not particularly reduce their enthusiasm, and they maintained economic and military assistance towards the regime. A CIA’s covert support, instead, went from secret media and funding propaganda projects aiming at clearing the military government’s poor international image, to cooperation and support for the vicious DINA. Moreover, the records belonging to this period attested to the U.S. policymakers’ efforts to downplay the abuses of the regime.

Accordingly, the United States was helping the Chilean government to survive and did not want any issue to stand between their bilateral relations. The United States governments not only helped the Chilean government to survive despite its extremely undemocratic practices but even failed to protect its citizens from the abuses of the Pinochet’s regime. In fact, soon after the coup, since Washington did not want any issue to stand between the bilateral relations of the two countries, it preferred not to investigate properly first the disappearance and then the execution of two American citizens living in Chile. As admitted in later declassified records, the White House had many reasons to believe that the Chilean military could have been responsible for the murders of Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi. Still, it refrained from confronting the regime with the evidence, lest it might affect their relations with Pinochet. The U.S. State Department even withheld to the families of the victims the information that they possessed, and the cases remained practically ignored for twenty-five years. With the release in 1999 and 2000 of hundreds of heavily censored documents the Horman family at least learned that in 1976 some U.S officials came to the conclusion that the “U.S. intelligence may have played an unfortunate part in Horman’s death”. In 2014, a judge of a Chilean Court upheld a decision to charge two Chileans and claimed the U.S. military intelligence services played a key role in the killings of the two Americans. “The military intelligence services of the United States had a fundamental role in the creation of the murders of the two American citizens in 1973, providing Chilean military officers with the information that led to their deaths”, the ruling said.

By the end of 1974, the Ford administration, which was mainly represented by the figure of Henry Kissinger, then-Secretary of States, was strongly resisting the U.S. Congress for the restrictions on assistance to Chile it had started to impose. To be more precise, the Congressional criticism for the executive branch’s support to the dictatorship mounted exponentially with the revelation of the CIA’s past covert operations in Chile in the 60s and early 70s. The Congress, fuelled by this knowledge, displayed a strong condemnation and passed a series of laws entrenching human rights as a prerequisite to U.S. foreign aid. At this point, the Department of State, rather than using the United States’ influence to press the military regime to respect the Chilean citizens’ rights, again, opted to sacrifice human rights. The transcripts of several secret meetings among American high officials reveal that it was reasserted that the U.S had to “balance their overall interests” and so human rights were just one little element if compared to the whole of the U.S interests. It follows that, in the records taken into consideration, the U.S. policymakers continuously sympathised with the Chilean military and did everything to challenge or circumvent Congressional restrictions until the end of Ford’s term. The restrictions were defined as a “disaster”. The transcripts of the conversations also capture Kissinger’s worry at the idea of having the human rights standards as a precondition to foreign aid to Chile or other countries, who had openly claimed the human rights question as a “silly question”.

In the conversations between the American and the Chilean officials, the U.S. part repeatedly apologised to the Junta for the criticism it was receiving and reassured them about the U.S. assistance despite the obstruction of the Congress. In the few cases in which they called Pinochet to respect human rights, it was done timidly and in the name of reducing an international criticism which would have interfered with the United States Government’s ability to provide assistance. Therefore, the warnings were not carried out in the name of human rights but for the protection of the United States-Chile interests. Kissinger even mocked his staff for expressing worries over human rights, saying that State Department officials were working at the Department of State and not as clergymen only because there were not enough churches for them.

Washington’s combination of reassurances and appreciation of Chile remained unchanged by mid-1975 even if the number of killings and disappeared persons increased in the country. The declassified records proved that the State Department and the CIA had extensive knowledge of the fact that these crimes were the result of pre-Condor operations and the “Operation Condor”. Condor was the Chilean-led network of Southern Cone secret-police agencies cooperating in eliminating political opponents at home and abroad.

The White House, nevertheless, decided to basically ignore the evidence on Condor’s operations and not to confront Pinochet in fear of offending him. In the light of the information U.S. officials possessed, they could have thus detected and prevented the subsequent act of international terrorism taking place in the United States. Operation Condor killed Orlando Letelier, former Allende minister and Ambassador to Washington, and Ronni Moffitt, his assistant, in Washington. At this point, CIA and the Department of State had every reason not to believe the Chilean government’s refusals of responsibility and could have easily unmasked the crime; instead, they went on absolving the regime and even concealed some evidence to the U.S. Justice Department. According to Peter Kornbluh, author of The Pinochet file: a declassified dossier on atrocity and accountability, they aimed to hide the U. S’s security apparatus’ negligence for minimising the situation up to the previous day.

If from 1973 to 1976, the Nixon and the Ford administrations essentially turned a blind eye towards the military government’s systematic violations of human rights, the situation changed with the election of Jimmy Carter in January 1977. His administration proved to be opposed the military government on the principle: Carter took office by promising a commitment over making human rights as a prerogative for the formulation of the U.S. foreign policy. Following this line, his approach to Chile was no longer the one of “balancing of interests”, but it was more about a U.S. foreign policy opened to give human rights’ concerns a fundamental role. In fact, the Chilean-United States relations followed a new path as the President immediately distanced himself from the dictatorship and, instead of resisting the U.S. Congress, he relied upon the existent human rights legislative groundwork it had enacted. The allocation of foreign aid to Chile was thus deeply influenced and practically cut.

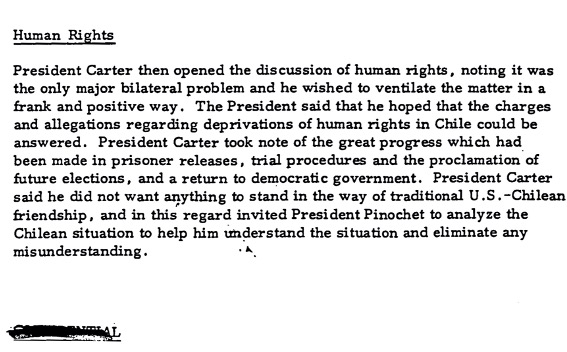

Certainly, he did not totally break with the regime but publicly and privately condemned its abuses. The communications (See Document 4) between Carter and Pinochet were characterised by Carter’s pressures over the improvement of the human rights situation, which he defined as the only obstacle in their friendly relations.

Document 4: The United States White House, President Carter/President Pinochet Bilateral, Memorandum of Conversation, 06 September 1977.

The declassified files thus proved a different attitude, both in the private exchanges within Washington, and in the communications with the government of Chile. Thanks to Carter’s change, of course, the military regime showed some initial signs of moderation, and it seemed interested in improving its undemocratic practices. However, their relationship rapidly deteriorated when, from 1978 onwards, the United States intensified the investigation over the Letelier-Moffitt assassination because of new revelations over DINA’s involvement. Pinochet refused to cooperate and in accordance with Manuel Contreras, the ex-chief of DINA, even enacted a campaign to discredit the United States and accused the CIA of the killing. The uncooperative and defiant attitude of Pinochet finally induced the Carter administration to apply a series of diplomatic, military and economic sanctions until the end of its term, when an actual break with the regime took place (See Document 5). Even though some Congressmen lamented the sanctions Carter imposed were too weak and failed to represent an impact to the military, the President's success in respect to Chile went beyond his ability to apply particularly severe sanctions. The significance of the Carter presidency relied on the fundamental role given to human rights in the making of the U.S. foreign policy towards Chile.

Document 5: United States Department of State, Policy toward Chile, 22 October 1980.

In conclusion, the availability of declassified documents allows both an inner and direct understanding of how crucial decisions toward Chile were formulated and a reconstruction of the interactions between the two countries. They demonstrate the degree to which, in the name of the U.S. broad interests, the Nixon and the Ford presidencies were complicitous with the Pinochet government, assisting in its consolidation while ignoring the most horrible practices of his regime. They also testify that, during the Carter administration, differently from the previous ones, the human rights concerns were given a priority over other foreign policy considerations to the point that all this caused the souring of the relationship between the two countries.

2/6/2020