Human rights and international arms trade: RWM Italia’s involvement in the Yemen Conflict

Table of Contents

- Business as a subject of international law

- Business human rights obligations

- International arms trade

- Complicity in war crimes

- The case of RWM Italia S.pA. in the Yemen conflict

- Conclusion

The developments of international law have been ignoring some of the most powerful non-state actors, transnational corporations and other business enterprises. Some scholars stated that international criminal liability for corporations is the “the next legal discovery”, but so far it is surrounded by speculation and controversy.

The international arms trade is among the most sensitive business sectors. Operating actively in conflict-affected areas, it can influence the evolution of the conflict and provide support to the parties. Arms trade can be complicit in the commission of war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity.

This article discusses the position of business under international law and what their human rights obligations are. In specific, it is focused on international arms trade and its possible contributions to war crimes, taking the case of RWM S.pA. involvement in Yemen as a case study.

Business as a subject of international law

Traditionally, States have been considered the only subject of international law. Corporations, on the other hand, belonging to the private sphere, are subjects of domestic legislation, under which they have enjoyed the status of legal persons. Business entities have used their exemption from international law to avoid international obligations, but recently accountability and transparency are expected from them as well.

The jurisprudence of the international tribunals is quite clear on the matter of international criminal liability for corporate actors. The International Military Tribunals established after World War II specifically ruled that: “[c]rimes against international law are committed by men, not by abstract entities […].” Similarly, the Statute of the International Criminal Court in article 25(1) states: “The Court shall have jurisdiction over natural persons pursuant to this Statute.”

In both cases, when reading the travaux préparatoires, it appears that the rejection of criminal liability was not due to the absence of a legal basis, but rather it was a compromise influenced by political reasons.

Business human rights obligations

Further proof of the recent developments towards the codification of legal responsibility for the behaviour of business enterprises with regard to human rights is the multiple attempts to create an instrument to regulate and monitor business human rights obligations. The first attempts date back to the 90s when scandals of corporate abuses (Nike’s abusive workplace practices and Shell’s role in the violent episodes in Ogoniland and Nigeria) achieved global coverage. The answer was a movement known as Corporate Social Responsibility, which encouraged corporations to adopt codes of conduct, supply chain audits and other forms of monitoring. Soon after, “The Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with Regard to Human Rights” and the UN Global Compact (UNGC) were born. The former was at last rejected in 2004 after facing the furious opposition of governments and business enterprises, the latter recently celebrated its 20th anniversary and continues to be a common platform of suggestions and dialogue on the issue of business and human rights.

In 2005, the Human Rights Commission requested the UN Secretary-General to appoint a Special Representative to investigate the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises. Following this recommendation, Professor John Ruggie was appointed as Special Representative on Business and Human Rights from 2008 to 2011.

The work of Prof. Ruggie can be considered a watershed within the business and human rights realm. He produced two ground-breaking documents that today represent the existing legal framework on the issue of business and human rights: the “Protect, Respect and Remedy (PRR) Framework” in 2008 and, on its basis, the “UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs)”. The two documents were drafted after an extensive consultation process, during which prof. Ruggie involved all the relevant actors and stakeholders. He tried to achieve a fair outcome to satisfy all the different requests and needs.

Prof. Ruggie identified the lack of an authoritative focal point as the main issue. The international business community was swarming with multiple initiatives on the theme. The PRR Framework collects them in a single document. It is based on three core principles: “the State duty to protect against human rights abuses by third parties, including business; the corporate responsibility to respect human rights; and the need for more effective access to remedies”.

In 2011, the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights were endorsed. The Guidelines aimed to implement the PRR Framework, meaning that the Guidelines do not create new legal obligations, but rather work with the existing standards and practices, aiming at finding their shortcomings and then integrate them. The UNGPs are divided into the three macro-categories of “protect, respect and remedy”, providing a commentary to explain the meaning and implications for law, policy, and practice.

Neither the PRR Framework nor the UNGPs ever specifically refer to the international arms trade. The discourse uses more general terms, referring to the so-called sensitive business and business operating in conflict-affected areas. For these two categories of business, enterprises are requested heightened attention on how they carry out their activities, with impeccable transparency, due-diligence processes, and risk-assessment strategies. They are necessary to identify beforehand the possible abuses connected to their business activities and to avoid them.

After the end of Ruggie’s mandate, the Human Rights Council decided to establish a Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises. The mandate of the Working Group is to facilitate the dissemination and implementation of the PRR Framework, and the Guiding Principles, thorough good practices and lessons learned. Alongside the Working Group, the UN Forum on business and human rights takes place yearly to work as a global platform.

The latest endeavour of the United Nations on the issue of business and human rights is the drafting of a legally binding treaty. An open-ended intergovernmental working group on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights, established in 2014, is currently working on a draft text.

International arms trade

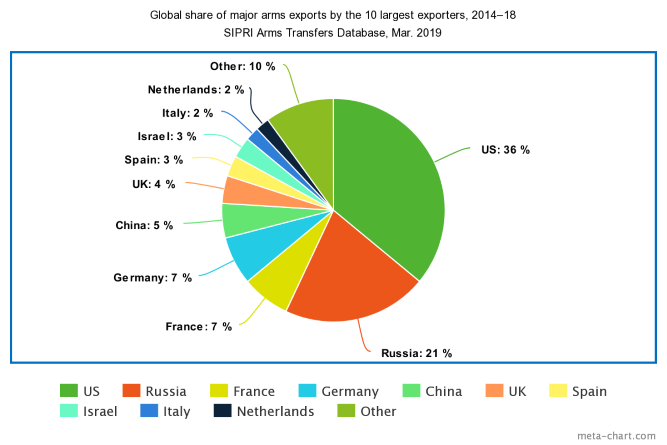

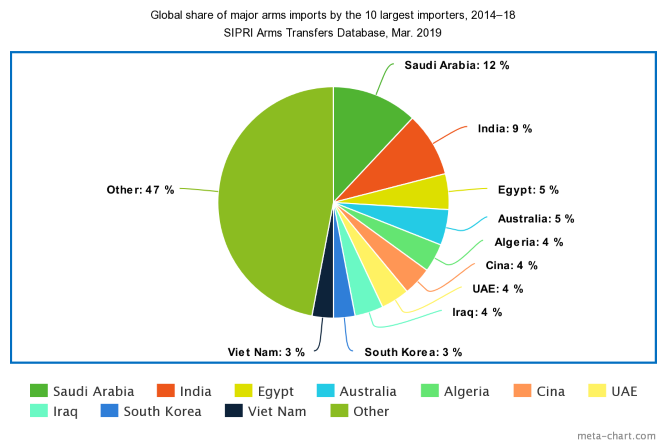

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) calculated that transfers of major arms in the five-year period of 2014 – 18 were 7.8% higher than in the period 2009 – 13, for a total of at least $95 billion spent in 2017. The 5 top exporters were the US, Russia, France, Germany and China. The top 5 importers of arms were Saudi Arabia, India, Egypt, Australia and Algeria.

The international arms trade is regulated by the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), which was adopted in 2013. As of today, the ATT has 110 State Parties and 31 signatories. Among the States that have yet to join are the top exporters the United States, and Russia. China became a State Party in July 2020. The ATT is the first treaty ever adopted that regulates the commerce of conventional weapons and sets common standards on the topic. It aims to regulate arms trade and prevent illicit arms trade and diversion. However, ATT faces structural weaknesses. It is simply impossible to regulate arms trade when the top 2 major exporters of arms globally, the US and Russia, are not parties to the Treaty.

Complicity in war crimes

The arms trade is a sensitive business, and the risk of contributing to atrocities is extremely high. The nature of corporate involvement in the execution of war crimes is usually indirect. A company participates indirectly by providing support for the direct prosecutor of the crime. The international law mechanisms to turn corporations accountable are the concepts of complicity or aiding and abetting the crimes. For a business to be considered complicit in a war crime, some conditions are to be met: its operations make it possible for the abuse to happen; it makes the situation significatively worse and exacerbates the abuse; its contribution makes carrying out the abuse easier.

The case of RWM Italia S.pA. in the Yemen conflict

The case of the involvement of RWM Italia S.pA. in the Yemen conflict is exemplificative. The case refers to the airstrike of October 2016. Allegedly, the Saudi led coalition carried out an airstrike that targeted a civilian home, killing instantly a family of six. The bomb remnants belonged to the MK80-family of guided bombs. Among the remnants, it was found the suspension lug, which presented a serial mark that traces back to the manufacturer, RWM Italia S.p.A., an Italian subsidiary of German Rheinmetall AG. No evidence on the scene points to the fact that the attack on civilians was collateral damage since the bomb found was guided and the closest military target, a military checkpoint, was more than 300 meters away. A group of NGOs presented a criminal complaint to the Italian Public Prosecutor of Rome and transmitted a communication to the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) of the International Criminal Court.

Regarding the instruments mentioned above, Italian law n.185/1990, which regulates arms trade, forbids the transfer of weapons to countries involved in a conflict or when it is known that human rights and humanitarian law violations are perpetuated. Italy has yet to incorporate the Rome Statute into its national legislation, so the violation does not constitute a war crime under Italian law. Regarding corporate liability, under Italian domestic law, administrative vicarious liability for corporate entities is admitted for crimes committed by their employees, but only in a restricted number of cases, which do not include violations of international humanitarian law or human rights.

The ATT, of which Italy is a State Party, forbids the transfer of arms. If the State at the time of the transfer knows that the arms or items would be used in the commission of genocide, crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, or other war crimes as defined by international agreements. The Italian National Authority for arms trade should have revoked the licences of RWM Italia and the company should have stopped the transfers when the Yemen conflict broke out.

As per the business and human rights obligations, the UNGPs can capture the fallacies of this case. The Italian State did not fulfil its obligation to protect human rights; RWM did not follow the obligation to respect human rights, and access to remedial mechanisms does not seem to be granted. Moreover, RWM Italia and Italian authorities refuse to acknowledge their responsibilities.

It is reasonable to presume that RWM Italia and Italian authorities knew that the weapons were used to commit war crimes. Saudi’s involvement in the conflict is a known fact. NGOs and human rights organisations have raised awareness since the very beginning of the conflict and have been trying to contact all the actors involved, including business enterprises, to make them aware of their contribution to the humanitarian and human rights violations. RWM Italia is a subsidiary of the German Rheinmetall. Two other subsidiaries of the German group are in the capital of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh. When carrying out risk assessments procedures or due diligence, members of every level of the supply chain must have been informed of the situation of Saudi Arabia and its involvement in the conflict. Moreover, subsidiaries must produce annual reports to explain the situation of their host country; therefore, it is plausible that the Riyadh subsidiary has sent an update to the mother company on the general tensions of the Middle East and in particular the Yemen Conflict. Furthermore, according to information provided by Rete Disarmo during an interview, recently, NGOs have started to participate in the shareholders meeting of companies and raising questions. These NGOs presented to the Rheinmetall CEO the situation of the Yemen conflict and the involvement of RWM Italia in the airstrike and asked their stance on the matter. The managers refused to answer, but they first-hand heard of the situation.

Conclusion

Four possible outcomes have been considered for the purpose of this article. The first is to prosecute individuals alongside the corporate entity. The jurisprudence of the ICC presents similar cases (The Van Anraat and Kouwenhoven cases) according to which the individuals can no longer hide behind the legal personality of the corporations. The second possible solution would be amending art. 25 of the ICC Statute as to include legal persons under its jurisdiction. The third is the development of a binding Treaty on Business and Human Rights and to institute a Committee or Treaty Body to monitor its implementation. The fourth potential solution would be the creation of a hybrid special tribunal for Yemen with the mandate of investigating and judging those involved in the atrocities committed during the conflict, including legal persons.

While arms trade is not an evil business per se, it is important to recognise its role as aider and abettor to the commission of war crimes. The arms industry must stop focusing only on profits while ignoring the context where the end-users are operating. In the meantime, the international community must work efficiently towards the adoption of a legally binding treaty on business and human rights.