Right to be forgotten for victims of image-based sexual abuse: A case of Telegram

Table of Contents

- What went wrong with Telegram?

- Right to be forgotten, Image-based Sexual Abuse, and Telegram – Why it went wrong?

- Being human in the digital world is about building a digital world for humans – Moving towards better protection for victims of IBSA

One of the most notable events in the first two decades of the 21st century was the explosion and rapid development of technology. The technological advancements, together with the widespread of digital platforms, have exacerbated current forms of violence against women and, at the same time, have introduced new ones, including technology-facilitated violence. Image-based sexual abuse (IBSA) falls into this new scope. IBSA is understood as creating or sharing private sexual images (i.e. nude, intimate photos and videos, etc.) without the consent of the person pictured, including threats to share them. Few examples of IBSA can be revenge porn, upskirting, sextortion, or fakeporn. It is worth noticing that online contexts and digital technology play an important part in the perpetration and harmful impacts of IBSA on victims due to the continued existence of their non-consensual private sexual images online. And what is worse is that the battle against digital platforms asking to remove the illegal contents seems to last forever. It adds more pressure and stresses to victims, making them more vulnerable to further abuse and violence.

Drawing from this perspective, the right to be forgotten (RTBF), namely the right to erasure under article 17 of the General Data Protection Regulation, has the potential to support victims in this endless battle against tech companies. Applying to the European Union (EU) and the European Economic Area, the RTBF gives victims as data subjects the right to ask digital platforms hosting their non-consensual private sexual images as data controllers to erase these IBSA materials. In practice, the RTBF did give the victims some advantages, and some big companies such as Google, Facebook, or Microsoft even developed their own policies giving victims a ‘theoretical right’ similar to RTBF without any geographical limitations. However, they are just ‘minority’ cases. Internet intermediaries usually act in a lawless way, among which Telegram appears to be remarkable because of its encryption technology for all received and processed data. The messaging app’s main selling point is privacy-focusing, and thus, it creates a hot debate about whether its policy is a necessary protection of privacy or an extreme way to protect it.

What went wrong with Telegram?

Aiming to provide a “truly free messenger, with a revolutionary privacy policy”, Telegram’s privacy policy did not change much when the GDPR came into force in 2018. By stating that the app does not “sell” your data “for ad targeting” or “to others”, and is not a part of any “family companies”, Telegram disclaims almost all responsibility concerning the data processing following GDPR.

In other words, Telegram guarantees anonymity for its users at the maximum level. But anonymity is a double-edged sword that may become a “cloak of invisibility” beneath that, shyness vanishes and all forms of human rights are abandoned. There is nothing wrong with respecting internet privacy, but the problem with Telegram is that its policy allows perpetrators to misuse the service for harmful purposes like IBSA. In theory, Telegram does ban users from abusing its technology for harmful purposes, including posting publicly available “illegal pornographic content”. Telegram will process legitimate requests when receiving reports or complaints by performing “necessary legal checks” and taking the content down when deemed appropriate. Few published cases have proved that Telegram did take down public channels spreading IBSA content, for example, in Korea (the Nth room), Israel, or Italy (“Stupro tua sorella 2.0”).

However, from another point of view, all these cases have attracted enormous public attention, and Telegram only responded on their official blog after being asked by many victims, victims’ acquaintances, media press and law enforcement. It is unclear if Telegram actively monitors its public places or depends only on user complaints of unlawful activity. In another case, Jamies Vincent, a senior reporter for The Verge, found Telegram bots scraping images on social media to create ‘deepfake’ nude content, whose quality varies from “obvious fakes” to realistically believable. Although the messaging app claimed to moderate third-parties bots, the investigation discovered that many stayed active for several months and produced more than 100,000 pictures without Telegram doing anything.

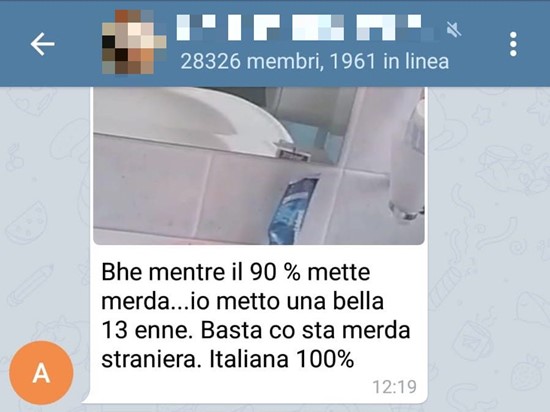

Moreover, processing only public content also means that any other content classified as “private”, such as chats between users or messages in private groups, will not be considered by Telegram no matter what. This is to say, if the IBSA contents are distributed in Telegram chats or group chats, the victims cannot request the app to erase the abuse materials even if they know the existence of these harmful contents. Besides, even though Telegram claims that user and group chats are “private”, they are actually not as private as they should be. A Telegram group may be a massive community where all types of information and material are exchanged between strangers. Groups are called “secret”, but the links to join the “secret” groups are spread within online communities publicly. Two researchers from the University of Milan and the University of Turin, Silvia Semenzin and Lucia Bainotti, conducted research about the spread of IBSA content on Telegram. According to them, it was very easy to access ‘private’ pornographic Telegram groups just by texting the admin of a porn site. Once they were a part of one group, they were given access to numerous others via other group members.

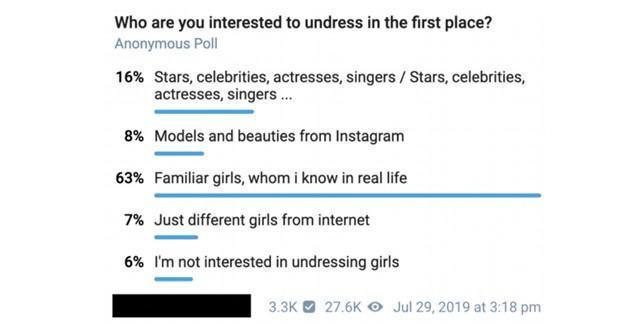

Semenzin and Bainotti examined numerous Telegram channels and groups, making it clear in the infobox that they exist to share content about “doxing and image-abusing girls”. Large groups can have more than 30,000 members and are active daily, in which the only rule is sharing images of current or ex-girlfriends, friends, or acquaintances. Participants can be dismissed if they fail to send non-consensual private sexual footage to the groups. For smaller groups of less than 20 users, who are usually close friends, the targets can be specific girls that they all know. IBSA materials can also be distributed together with mainstream porn groups, in which the number of members can exceed 60,000 people.

There are also secret groups and public channels, with around 60,000 members, created to share sexual images made with a hidden camera. The abuse contents are secretly recorded photos of women during sexual acts and upskirting pictures in public spaces such as the beach, shops, and the street. URLs to IBSA contents on other platforms like Facebook and Instagram are also shared in Telegram groups and channels to further harm victims. The perpetrators on Telegram also create bots to gather, store and share non-consensual private sexual images and personal information of victims, automating the spread of IBSA images among channels and groups.

Since most of the Telegram groups are private and secret, victims have found it almost impossible to get their private sexual images or personal information deleted from the platform after being distributed without their consent. Moreover, the number of people in these channels and the speed at which both human users and bots spread this content makes this task nearly impossible. This approach is critical to Telegram’s main value proposition as a privacy-preserving messaging service, allowing its users to exchange unlawful information with little to no consequences. That being the case, it is clear that the ‘public vs private’ policy of Telegram is failing to protect victims of IBSA happening on their platform. Telegram’s architecture, content moderation policies, lack of punishment, and “established gendered scripts” lead to the creation of a discourse that eventually normalises IBSA acts. Furthermore, while promoting the right to privacy of its users, Telegram also minimises the right to privacy and data protection of other data subjects such as victims of IBSA.

Right to be forgotten, Image-based Sexual Abuse, and Telegram – Why it went wrong?

Telegram is just one of many cases that proved how limited the legal framework in general, and the RTBF in particular, are when it comes to new technology-facilitated violence such as IBSA. First of all, the territorial scope and extraterritorial applications of the RTBF under the European data protection law are significant challenges when addressing transnational violence like IBSA. Given the nature of the Internet, the law is limited when it has to deal with the perpetration outside its physical borders. While Google and Facebook are taking proactive steps to detect IBSA globally and independently from the RTBF or GDPR, Telegram only responds to victims because of law requirements. Besides, the GDPR also does not explicitly instruct how the data should be erased, which is a gross omission for data protection legislation from a legal point of view. It leaves the ground for digital platforms to decide by themselves but, at the same time, creates a gap in how data controllers handle illegal data in their systems.

Another problem with Telegram is that it addresses only the “illegal pornographic content”, which is both too broad and too narrow when it comes to the case of IBSA. What is “illegal”? What is considered “pornographic content”? There is no one who could answer these questions except Telegram, which (again) leaves the matters into its own hands for each case. The ambiguous and unclear phrase makes it confusing to target all forms of abuse and violence happening on the platforms, which impact the removal practices of the messaging app and further the victims’ safety and privacy.

All in all, it is crucial to notice the liability of service providers like Telegram since they are the main factors that create the space for the abuse to happen in the first place. There are various problems surrounding the practices of Telegram in fulfilling its liability, such as its unregulated actions towards removal requests of victims and transparency deficits between the policies and practice of erasing data. Most importantly, the current policies and systems are putting the onus on victims to report and persuade actions from the data controller. Due to ambiguous guidelines, lack of transparency and unwillingness to collaborate, victims’ or their authorised representatives’ capacity to seek the protection they should receive can also be limited. For example, a recent study by the Italian advocacy organisation PermessoNegato revealed “refractory” and “complacent” responses of Telegram to reports of IBSA. Yuval Gold, a victim of IBSA in the Israel Telegram case, expressed: “I don’t think Telegram can delete my photos. And if they do it, there are 1,000 people that have my photos on their phone, so it doesn’t matter.”

Being human in the digital world is about building a digital world for humans – Moving towards better protection for victims of IBSA

Nonetheless, it led to the last question of who should hold responsibilities in this scenario. It is not the sole responsibility of tech companies or the governments to protect every woman from violence and abuse but requires the alignment of multi-stakeholders. Technology is continuously changing, and a growing number of technologies are being misused to violate other people’s rights, like encryption technology in the case of Telegram. Only when service providers and the States address such abuse properly can they shift norms, policies, and practices in informed and responsible ways that result in a better cultural change.

In the end, discrimination against women, misogyny and other gender-based violence are becoming more and more challenging in this digital era, but we fall behind in reactive and proactive remedies. It is time for technology companies and the States to step up and fulfil their due diligence in ensuring human rights for everyone without any geographical limitations.