The Criminalisation of Humanitarian Assistance Towards Irregular Migrants in the EU

Table of Contents

- The nexus security-migration in the EU

- The criminalisation process: legal aspect, prosecutions and social hostility

- The Italian scenario: Search and Rescue NGOs turned into criminals

- Conclusions

All over Europe we are witnessing increasing hostility, attacks and prosecutions against civil society actors engaged in providing humanitarian assistance to migrants and advocating for their fundamental rights. This is primarily a consequence of the high rates of criminalization of irregular migration within the European continent. To address the process of criminalisation of irregular migrants and people assisting them requires the acknowledgement of its broad conceptualization, entailing all measures aimed at deterring and punishing acts of solidarity towards migrants: not only legal aspects - such as the presence of administrative or penal sanctions -, but also all political discourses, social practices and judicial prosecutions aimed at intimidating and delegitimizing humanitarian actors and their operations.

The nexus security-migration in the EU

In order to understand the origins of the association between irregular migration and the criminal law field, it is fundamental to look at the long-standing nexus between security and migration intrinsically rooted in the European policies. Especially since the ‘80s, European States started to harmonize their legislation about migration, initiating the process called “Europeanisation” of migration. As progressively reiterated in different Intergovernmental Fora, Strategic Programs and EU legislative acts, migration has always been treated as a security matter, to the extent that it is appropriate to talk about “securitization” of migration. The way to ensure justice, freedom and security among European citizens was to protect them from external “threats” such as international crime and “illegal” migration, and combating them through stricter border controls.

In fact, the achievement of the internal security has been a fundamental justification for the management of migration as part of the externalization of European security policies, through strict border controls (Frontex and Eurosur), mobility partnerships, the Schengen Visa regime and several agreements with countries of origins to reduce the migratory incoming flows (such as the 2016 EU-Turkey deal or the 2017 Memorandum of Understanding signed between Italy and Libya). Similarly, the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) presents relevant securitarian implications that are functional to the policy of migration control: the collection of migrants’ biometric data, the interdiction of secondary movements in compliance with the Dublin regulation, and the strong emphasis on detention and removal measures.

At present, Member States appear to be still unable to find a political agreement upon a more sustainable and responsible management of incoming migratory flows. In fact, at the European Council meeting that took place on the 28th and 29th of June 2018, Member States agreed on taking care of rescued people on EU territory only on a voluntary basis, while they stressed once again the priority of strengthening controls of external borders and halting the so-called illegal migration.

The criminalisation process: legal aspect, prosecutions and social hostility

To understand and analyse the critical issues of the current situation, it is necessary to observe how the subjects of irregular migration, facilitation and humanitarian assistance are regulated under international and European law.

At International level, the legal standard dealing with this issue is the UN Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air (2000). It provides a definition of smuggling, described as “the procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident” (Art. 3), and demands each State Party to take measures in order to punish these criminal offences (Art. 6). Originally, the Protocol focuses its strategy to combat smuggling on the act of smuggling and not on migration itself, as it is made clear by Art. 5, that explicitly prohibits the criminalisation of persons being the object of conduct of smuggling. Moreover, the reference to “financial or other material benefit” was included as an element of the definition in order to ensure that the activities of those who provide support to migrants on humanitarian grounds or on the basis of close family ties do not come within the scope of the protocol (see the Ad Hoc Committee interpretative note on article 3 - subparagraph a included in the Travaux Préparatoires). However, the insufficient or partial implementation by States Parties reveal how, at regional and national levels, this principle has been disregarded, not only through a constant confusion between irregular migrants and smugglers in the public discourse, but also by leading numerous discredit campaigns carried out against individuals and NGOs providing humanitarian help to migrants.

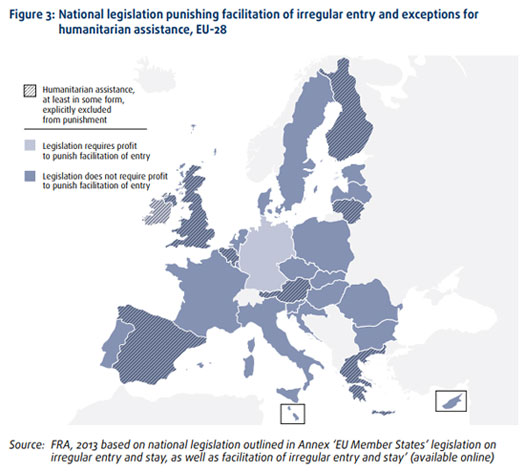

With regard to the European case, the legal framework regulating these issues is the Facilitators’ Package adopted in 2002, which includes the Facilitation Directive, defining the punishable offences, and the Framework Decision, setting the respective applicable sanctions. By conducting an attentive comparative analysis, it is possible to observe that the Package is not fully compliant with the provisions contained in the UN Protocol. The inconsistencies relevant to this study concern primarily two aspects: first, the fact that in the Facilitation Directive (Art. 1) the formulation “for financial gain” exclusively refers to the facilitation of irregular residence, while it is not mentioned with regard to entry or transit. This essentially means that any person who aids, abets or in any other way facilitates irregular migration shall be liable to be punished under criminal law. Secondly, the problem of the vagueness around the humanitarian issue, as the Directive leaves Member States the discretion to not impose sanctions on who provide help to migrants (Art. 1(2)). The most concerning aspect is that by not creating an obligation upon States to refrain from prosecuting humanitarian actors, the room for criminalisation is wider.

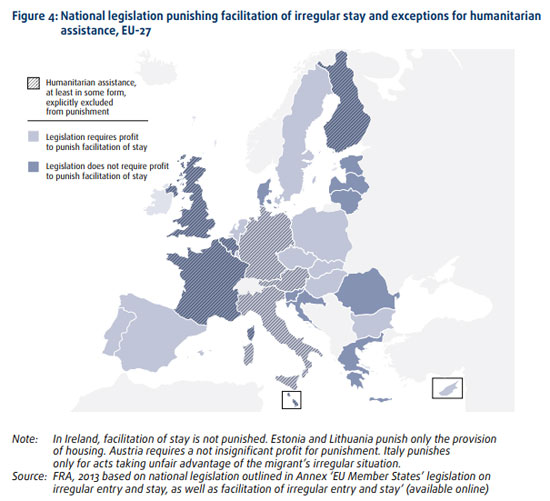

In fact, according to the research realized by the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights in 2016, the facilitation of irregular migration is punished in all 28 EU Member States, with different types of sanctions.

The existence of administrative and penal sanctions punishing facilitation and the absence of clear humanitarian exemptions works as a deterrent for individuals engaged in providing assistance to undocumented migrants. Cases of criminalization have multiplied in recent years, to the extent that some civil society actors have coined the challenging term “crime of solidarity” (delit de solidarité) with the intention of strongly criticizing all the effects of the extensive criminalization campaigns carried out by national EU States. It is for instance the case of the French farmer Cédric Herrou, who became a known symbol of solidarity towards migrants after receiving a four-month suspended jail sentence in August 2017 for helping some migrants to crossing the Italian-French border and reside in France; many other examples could be reported (see for instance the Belgian case of les hébérgeurs and the one of the volunteers of the Emergency Response Centre International in Greece). The existence of such legal measures are aggravated by the political hostility and intimidation that many Governments and media address to undocumented migrants and human rights defenders, which is making them experience harsh forms of criminal stigma and social isolation.

The Italian scenario: Search and Rescue NGOs turned into criminals

Due to its strategic position in the Mediterranean Sea, Italy has been the subject of many controversial stances concerning the management of migratory flows, especially in recent years, when a pronounced anti-immigration campaign has been linked to security issues and used for electoral purposes. Even though the national legislation provides exemptions from criminalization on humanitarian ground, “being irregular” is a crime under Article 10-bis to the Testo Unico sull’Immigrazione sanctioned with a fine up to 10.000€, while the facilitation is punished with a fine of 15.000€ and with imprisonment from 1 to 5 years (Art. 12). Despite the existence of a humanitarian exemption, cases of political and judicial criminalization are rising sharply as hate and discredit campaigns directed at human rights defenders have strengthened - as also highlighted by the several Special Rapporteurs of the OHCHR.

The most evident and worrying criminalization campaign is the one directed at NGOs leading search and rescue operations (SAR) in the Mediterranean Sea. The idea that SAR activities were a “pull factor” for refugees was disseminated by many politicians around Europe and afterwards repeated by both Frontex and European institutions, which began to make the link between life-saving operations in the Mediterranean and the increasing influx of migrants based on alleged smuggling activities (theories and allegations that have been proven wrong by several research, among which the study of MSF). The enhancement of Libyan intervention for border control and SAR activities agreed through the Memorandum of Understanding implied - on the other hand - the de-legitimation and “rationalization” of humanitarian NGOs at sea, which resulted in an effective obstruction of their actions. After consultations with the EU Commission, in July 2017 the Italian Government implemented a Code of Conduct on NGOs aiming at strictly controlling and limiting their interventions. On the ground of serious human rights concerns - also reported by the OHCHR - some organizations, such as Médecins sans Frontières and Jugend Rettet, refused to sign the agreement. Since then, several NGOs vessels started to be prevented from docking at Italian harbours, in line with the new Government “closed harbours” unilateral policy. NGOs carrying rescued migrants on board were treated as criminals cooperating with smugglers, and therefore left out of territorial waters for days (see for example the case of the German Sea-Watch of January 2019). Many other vessels, such as Proactive Open Arms, Lifeline, Juventa etc., have been seized and/or the NGO investigated for facilitation of irregular migration or smuggling. Even though all accuses have been dropped and no evidence have been found, the discredit rhetoric hasn’t stopped and the scenario has got worse after the adoption of the Security Decree (2018) and the Security Decree bis (2019) - strongly promoted by the Ministry of Interior Matteo Salvini - which introduced harsh restrictive measures regarding the reception system and border control. In particular, the first one included the dismantling of the SPRAR structures and the abolition of humanitarian protection, while the second one attributes to 3 Ministries the decisional power to “restrict or prohibit the entry, transit or parking of ships in Italian territorial waters". Moreover, according to the law "in the event of violation of the prohibition of entry, transit or parking" in the territorial sea, the skippers of NGO vessels who have rescued asylum seekers will face fines between €150,000 - 1 million (art.2), risking to get arrested and see their vessel being seized. The law has already produced its effects - see for example the case of Carola Rackete, captain of the Sea-Watch 3 arrested for docking with 40 migrants on board, and the Mare Jonio vessel of Mediterranea, that have recently been fined with 300.000 € for entering Italian waters; many civil society organizations and UNHCR have expressed their serious concerns about the Decree and its compliance with international human rights obligation, calling on the Italian government to revise it.

Conclusions

To conclude, the overall European criminalising scenario is surely concerning and needs to be properly tackled, to ensure the efficiency of humanitarian actors and the actual protection of migrants’ fundamental rights. First of all, to manage migratory flows in a responsible way and with a human rights-based approach, I believe it is necessary to change the cultural and political belief according to which migration is essentially a security issue to be regulated through criminal provisions. In fact, it is worth keeping in mind that the irregular status derives from a series of legal administrative circumstances and not from the singular intention of committing a crime.

Moreover, in order to manage the complex phenomenon of migratory flows in a sustainable way, EU Member States need to find common solutions based on responsibility-sharing mechanisms, aiming at alleviating the burden on front-line States and ensuring undocumented migrants their right to apply for asylum. In a legal perspective, the EU Commission must absolutely amend the Facilitation Directive in order to make it consistent with the UN Smuggling Protocol, by introducing the “financial gain or other material benefit” as requirement to punish (also) the facilitation of entry, and by making mandatory upon EU Member States the exemption of humanitarian assistance from criminalisation. Finally, with regard to the Italian situation, the obstructive criminalizing rhetoric towards SAR NGOs must immediately end. Accordingly, the controversial Memorandum of Understanding signed with Libya should be dismissed, and the internal Security Decrees deeply revised in favour of a respectful approach towards the international human rights obligations Italy is bound to.