The International Labour Organisation and Child Labour: From the Foundation to Nowadays

Table of Contents

- Introduction: child labour in the international framework

- The first steps to reduce child labour

- The ILO’s major achievements in the fight against child labour

- Child labour during the Covid-19

- Conclusions

Introduction: child labour in the international framework

Child labour, defined as “work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential, and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development”, has been present in the international community since the Industrial Revolution. Because of its intensity, governments have sought to prevent and monitor child labour at both national and international levels. The foundation of the ILO in 1919 represents the highest peak of states’ interest in commonly adopting international standards to prevent and protect the rights of workers, including children. Indeed, since 1919, the ILO has been a key player in tackling child labour, providing a peaceful arena in which employers, governments and trade unions can work together to protect workers’ rights. Today, the ILO is the leading international organisation committed to the elimination of child labour, having produced numerous legally binding documents and operational instruments to regulate the minimum age and eliminate child labour worldwide. The high number of ratifications and the participation of member states in ad hoc operations over the past decades are remarkable achievements in the fight against child labour.

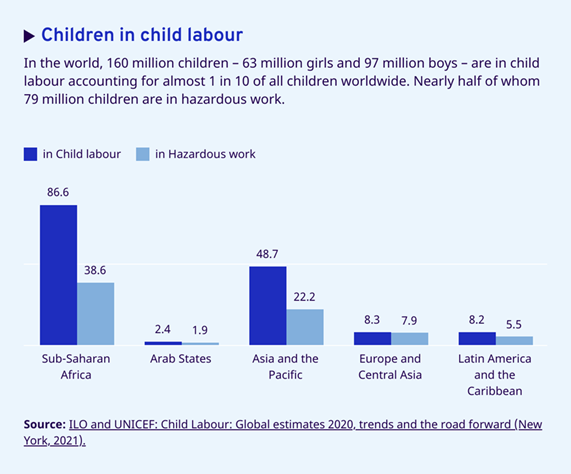

However, the international community is not achieving any other remarkable results in this regard. In fact, as stated by the ILO’s report of 2020 on global trends, more than 160 million children between the ages of five and seventeen are currently employed in the worst forms of child labour. These statistics show that, despite the numerous instruments created to combat child labour, the ILO has not succeeded in its attempt to eradicate the phenomenon or, at least, to reduce its intensity. The ILO’s mission has been virtuous in creating international cooperation and raising national awareness, but relatively ineffective in achieving the expected results. Undeniably, the ILO’s system of legal obligations against child labour seems to have weaknesses that might undermine the organisation’s ability to achieve its goal of completely eradicating child labour worldwide.

The negative and positive aspects of the current approach can be traced back to the ILO’s own history. Indeed, by monitoring the evolution of the ILO’s action against child labour, it is possible to highlight the improvements and shortcomings typical of a specific phase, which can still be observed in the current approach.

The first steps to reduce child labour

From 1919 to 1948, the ILO produced seven conventions to establish a common minimum age bar in the workplace and to regulate night shifts for children. The international obligations formed represented a great success for the ILO and for the universal fight against child labour. Despite the difficulties posed by the aftermath of World War I, the Great Depression and the resulting mass unemployment, the organisation did not miss the opportunity to produce international Conventions that could improve the national battle against child labour.

The framework established had significant key elements that are still fundamental to the ILO’s overall mission today. First, the Conventions emphasised the extent to which youth work can be a serious threat to health, human development, and morality. Secondly, delegations, especially trade union delegations, firmly pushed for school attendance as a good way to reduce the high rate of children employed in various sectors. Third, it was stated for the first time that the protection of children in the workplace should be included in the more complex universe of human rights.

Despite these important legal foundations, some serious problems were evident. The organisation failed to protect children in some of the most dangerous sectors: family businesses and agriculture. A common misunderstanding about the nature of child labour was the main obstacle. National governments argued strongly that working in a family industry or in open-air settings could not be dangerous to children’s lives or health. This general idea adversely affected the international protection of children, resulting in an incomplete set of legal obligations. In addition, the organisation left huge margins of discretion to States, both legally and practically. Indeed, the ILO failed to produce a universal legal definition of child labour and to establish a common minimum age of employment, creating a major gap in international and, therefore, national law. Then the lack of a common international programme to technically support states in implementing international standards made the picture even more precarious.

The ILO’s major achievements in the fight against child labour

From the 1970s to the late 1990s, the ILO managed to make major improvements, overcoming the main obstacles posed by the lack of joint legal and operational action. The instruments produced in this period are the cornerstones of the current international framework against child labour. These are: the Minimum Age Convention of 1973, the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention of 1999, and the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC). It is important to emphasise the novelty that each instrument brought to the international arena to truly understand the organisation’s main achievements.

The ILO Minimum Age Convention of 1973 (n.138) sets the bar for the universal minimum age at fifteen, allowing states to set a minimum age below fourteen with a promise to meet the fifteen-year obligation as soon as possible. It states that:

The minimum age […] shall not be less than the age of completion of compulsory schooling and, in any case, shall not be less than 15 years. […] A Member whose economy and educational facilities are insufficiently developed may initially specify a minimum age of 14 years.

In addition, schooling is given a central role in the international legal framework as the main instrument to effectively reduce the total number of working children. Despite Cold War tensions, the document was widely ratified by states, representing a new and growing interest in the international community to defend children’s rights.

The ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention of 1999 (n.182) finally provides a legal definition of child labour, eighty years after the founding of the ILO. Member states agreed to define that:

The term comprises:

(a) all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery, such as the sale and trafficking of children, debt bondage and serfdom and forced or compulsory labour, including forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict.

(b) the use, procuring or offering of a child for prostitution, for the production of pornography or for pornographic performances.

(c) the use, procuring or offering of a child for illicit activities, in particular for the production and trafficking of drugs as defined in the relevant international treaties.

(d) work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.

The definition seeks to refer to all those circumstances that, by their essence, maybe mentally, physically, socially, or morally dangerous and harmful to children and prevent them from attending school. It basically includes all those practices in which children work against their will or are threatened to work. Slavery, prostitution, work for illicit activities and others are all classified as work from which children cannot easily escape and, in most cases, seriously harm their physical and psychological development. To effectively protect children’s lives, the Convention gives member states relevant guidelines on how to construct national frameworks, while allowing a wide margin of discretion. This flexible rigidity has ensured universal consensus and a high number of ratifications.

The International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC), launched in 1992, has ensured the strengthening of the ILO’s legal action on the reduction of child labour. It is the ILO’s first operational programme to address child labour through international cooperation. This permanent campaign is designed to: collect data; monitor trends; inform member States, the Organization and civil society; and take appropriate action against injustice. The programme has enabled the ILO to take more decisive action and launch intensive international missions. Its missions have been essential in reducing child labour in the new globalised community.

Child labour during the Covid-19

The covid-19 pandemic in 2020 seriously undermined the ILO’s mission against child labour. During the pandemic, national economies became victims of events, causing enormous negative effects on the population. Inevitably, the pandemic has damagingly brought States in an unprecedented situation in which the protection of human rights has mostly failed. Economic instability, caused by a pandemic, has forced States to face new challenges. Mass unemployment, national GDP decline, remittances reduction, and augmentation of informal economies have seriously affected the quality of life of humans, augmenting hunger, and the number of vulnerable people. As a consequence, the number of children employed in the worst forms of child labour drastically increased.

ILO’s reports before Covid-19 estimated that, by 2020, the number of children employed in the worst forms of child labour had to be 137 million. Unfortunately, the goal was not achieved by the Organisation, rather it seems to be too far from reality. Indeed, the general insecurity has led to a serious increase of children working in hazardous work, especially in the most vulnerable areas of the world.

This trend may be explained by the incapability of the Organisation to ensure a constant national implementation of anti-child-labour legislation while facing new threats to economic performance. However, the ILO has planned national actions at different levels to counter face the actual crisis, in partnership with a new programme to deal with child labour: the Alliance 8.7. The main fixed objective is to identify the main causes, to elaborate on effective responses, and to take solid actions to tackle child labour. The launch of the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour in 2021 has been one of the most relevant actions of the ILO to spread awareness and recreate solid international cooperation.

Conclusions

This article tried to present, through a historical analysis of the ILO’s work, the strengths, and weaknesses of the actual fight against child labour. The analysis of three different periods, from 1919 to 1948, from 1970 to 1990, and from 2020 to nowadays, made the following observations.

Firstly, the examination has shown that the International Labour Organisation has built a remarkable international legal framework, obliging states to dialogue on child labour and commonly agreeing to set universal standards. The capacity of the Organisation to involve states, trade unions, and employers has generated a good set of anti-child-labour instruments, such as the 1973 and 1999 ILO Conventions, and the launch of the IPEC programme. The legal framework created has ensured the elimination of child labour in many areas of the world and, in addition, a significant reduction in critical geopolitical areas.

Secondly, it has shown that the Organisation has some structural flaws that might undermine the missions’ effectiveness to protect children. It has created a legal framework that is gravely precarious, due to the lack of legislation on children employed in agriculture and family businesses. This lack of legislation is a matter of great urgency for the Organisation because 70% of the global rate of children between the ages of five and seventeen currently work in agriculture. Furthermore, the flexible rigidity, which has ensured universal participation, has contributed to the creation of a system that is unable to address child labour concretely. For last, the Covid-19 pandemic brought to light the Organisation’s difficulties in dealing with the national implementation of child labour, while dealing with unpredictable emergencies. As a result, child labour has dramatically increased, rolling back the positive results in the pre-Covid times.

In conclusion, it is possible to affirm that legislative and operational shortcomings must be addressed to reduce the high rates of child labour worldwide, trying to reinforce positive aspects and to improve negative ones. The Organisation must adapt, as it has done in the past, to new international circumstances and design new tactics against child labour to realise the best interests of the child.