Climate Justice 1 - Leaving Fossil Fuels in the Ground

Table of Contents

- Climate Crisis and Fossil Fuels

- The Delay in Global Climate Governance and the Need to Leave Fossil Fuels Underground

- The Yasuní-ITT Initiative and the Justice Implications of Leaving Fossil Fuels Underground

- From Yasunization Towards a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty

- To learn more

Climate Crisis and Fossil Fuels

Emissions resulting from the use of fossil fuels to power our energy system are the primary cause of the current climate crisis.

In 1997, physicist and climatologist Bill Hare published an article titled "Fossil Fuels and Climate Protection," which highlighted that the known fossil fuel reserves at the time, if burned, would release at least twice the amount of CO2 that the atmosphere could absorb while still keeping global warming below 2°C. Hare's study can be regarded as the first in a series exploring the concept of unburnable carbon, which is the quantity of oil, gas, and coal resources that must remain underground to avoid exceeding global average temperature increase thresholds considered critical for the planet's climate stability.

In the years that followed, research on unburnable carbon continued to evolve. The studies by McGlade and Ekins (2015) and Welsby et al. (2021), both published in the scientific journal Nature, represent two key milestones in this field.

In the first study, precise estimates are provided, for the first time, of the quantities of oil, gas, and coal reserves that must remain unburned (and therefore not extracted) by 2050 to ensure that global warming does not exceed 2°C. The results show that 35% of oil, 52% of gas, and 88% of coal must remain underground, and that the carbon budget available to humanity for meeting its climate goals is significantly lower than the projected production trajectories.

In the second study, Welsby and colleagues update the estimates of McGlade and Ekins, taking into account the 1.5°C global temperature limit established by the Paris Agreement in 2015, a threshold considered significantly safer than the previous 2°C target. With the adoption of more ambitious target, the volume of unusable carbon increases: approximately two-thirds of global oil and gas, and 89% of coal, must remain underground to prevent the most catastrophic impacts of the climate crisis.

The Delay in Global Climate Governance and the Need to Leave Fossil Fuels Underground

Despite the link between fossil fuels and climate change having been widely recognised for over 40 years, particularly since the establishment of the IPCC in 1988, international climate governance has been severely delayed in integrating fossil fuel regulation into broader climate policy.

It was only in 2021, during the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, held in Glasgow, that fossil fuels were mentioned for the first time in a final declaration, with a commitment to begin the phase-down of unabated coal power. Moreover, it was only in 2023, during the controversial COP28 in Dubai, that the parties reached an agreement to begin a just transition away from fossil fuels.

The urgency to begin a genuine discussion on how to equitably distribute the production and consumption of remaining fossil fuel reserves, in a manner compatible with climate stability thresholds, has yet to find effective resonance among governments.

Given current global levels of supply and demand, and in the absence of adequate fossil fuel regulation mechanisms, humanity is destined to face the severe consequences of climate change. To address this issue, government action has thus far focused primarily on reducing demand by seeking to replace fossil fuels with alternative energy sources, while delegating much of the mitigation efforts to the market, a strategy that is proving too slow and insufficient compared to the scale of interventions needed. Therefore, to remain within the carbon budget, reducing demand alone is insufficient; it is also necessary to limit the extraction of fossil fuel reserves by globally coordinating a rapid, orderly, and just exit from fossil production. In essence, mechanisms and regulations are required to ensure that a significant portion of existing fossil fuel reserves remains underground, guided by principles of justice and equity.

An emblematic experience in this regard was the Yasuní-ITT initiative in Ecuador in 2007.

The Yasuní-ITT Initiative and the Justice Implications of Leaving Fossil Fuels Underground

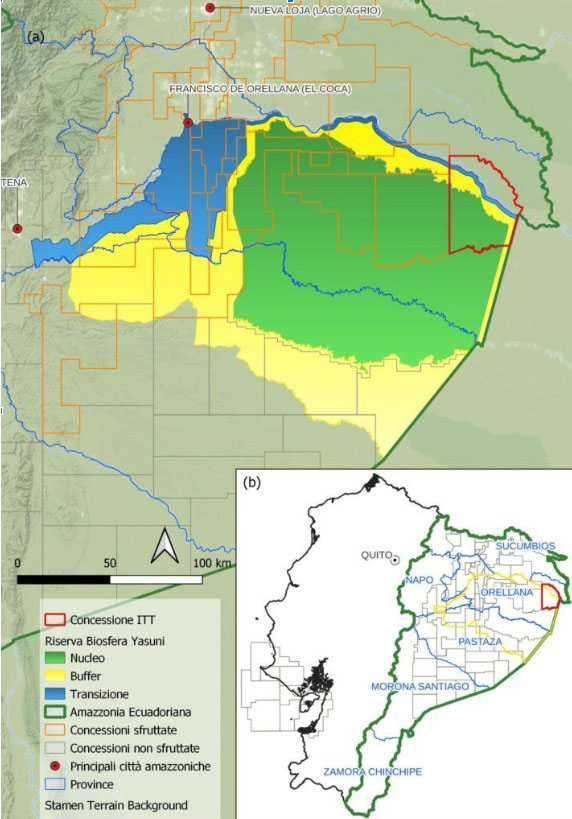

In 2007, the Ecuadorian government launched the Yasuní-ITT Initiative, a revolutionary proposal to leave the oil beneath the UNESCO Yasuní Biosphere Reserve, located in the Ecuadorian Amazon region, underground. The aim was to preserve biodiversity and protect the rights of the Indigenous Peoples who inhabit the area, while simultaneously mitigating climate change by preventing CO2 emissions from the use of extracted oil.

Specifically, the initiative proposed foregoing the exploitation of the oil reserves in the Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (ITT) field in exchange for adequate financial compensation from the international community. These funds were intended to support just energy transition pathways and promote sustainable territorial development in the region, focusing on biodiversity conservation and protecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Despite its ambition, the initiative raised only $200 million, a significant sum, yet far short of the $3.6 billion considered adequate compensation. This figure represented approximately half of the projected revenues from exploiting the estimated reserves, which amounted to about 20% of Ecuador's total reserves.

Framing of the Ecuadorian Amazon, the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve, and the ITT concession

In 2013, the failure to meet the financial target led the Ecuadorian government to declare the initiative's failure and definitively abandon the project.

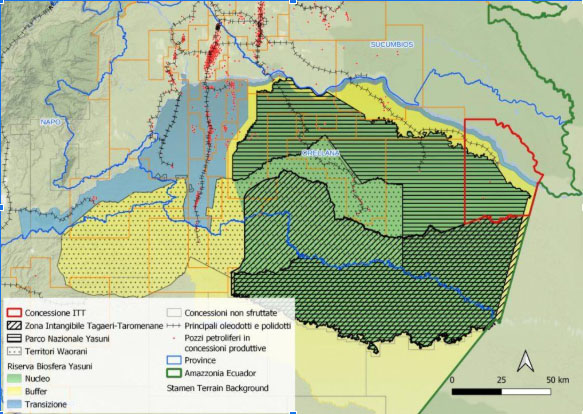

In 2016, extraction operations began within the reserve, inflicting irreversible harm on biodiversity and on the rights of the most vulnerable Indigenous Peoples, including the Waorani and the uncontacted Tagaeri-Taromenane people, who inhabit the Intangible Zone (ZITT), an area designated to uphold their right to self-determination.

In 2023, largely thanks to the efforts of civil society and indigenous movements opposing oil development, the Constitutional Court approved a referendum to keep crude oil underground within the ITT concession. The referendum, held in August of the same year, resulted in a victory for the "Yes" vote, which called for the cessation of extraction operations.

The Biosphere Reserve and the Tagaeri-Taromenane Intangible Zone, the "oil cage" in which uncontacted peoples are confined.

The Yasuní-ITT initiative raises at least three relevant issues related to the multiple dimensions of justice in the idea of leaving fossil fuels underground.

The first issue concerns the initiative's legacy, summarised in the concept of Yasunization, or "the bottom-up action to build an alternative to petroculture based on indigenous cultures, human and environmental rights for multiscalar climate justice" (De Marchi et al., 2023).

The initiative thus highlights the challenge of "where" fossil fuels should be left underground. On one hand, it contrasts the "technical" or "when" transition, exemplified by high-profile targets such as "net zero by 2050," with the less explored and less studied dimension, a more inclusive and participatory transition, a transition of people, places, and ecosystems. This latter vision emphasises justice that recognises the importance of protecting what lives above the ground and where it is located, a spatial and environmental justice, in contrast to the petro-capitalist vision that focuses exclusively on what is underground and its intensive exploitation.

Despite the growing demand for a fair and just transition away from fossil fuels, global oil and gas production has progressively increased in recent years. The devastating effects of fossil (and not only) extractivism directly impact the territories where these activities occur and the communities that inhabit them, giving rise to so-called "sacrifice zones."

Scenes of daily life in a sacrifice zone: in El Eno, in the province of Sucumbíos, Ecuador, a group of children plays in a school located next to an oil platform where gas flaring occurs (May 2019). Subsequently, the school was closed and relocated elsewhere.

The second issue raised by the initiative concerns the current challenges in cooperation between the Global North and South, and underscores the need for a more central role of climate justice in international dialogue. As highlighted by Leferna (2018), the initiative was innovative in being one of the first governmental proposals to include a vision of climate justice in global fossil fuel production. It argued that the developed world, having been primarily responsible for the climate crisis due to disproportionate use of fossil resources, bears an obligation to support developing countries in reducing their dependence on such resources. This argument is grounded in the logic of distributive justice recognised by the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (Earth Summit, 1992). Despite this innovative vision, the international community's response was weak and characterised by a reluctance to pay to keep fossil fuels underground, with only a few countries from the Global North willing to contribute to compensation.

Finally, the third issue relates to a shift in perspective on the climate crisis and the collapse of the biosphere, offering renewed impetus to research and movements advocating for keeping fossil fuels underground. Studies such as those by McGlade and Ekins, and Welsby et al., remind us that a stable, safe, and just Earth system, from both climate and environmental perspectives, cannot be envisaged without leaving a substantial proportion of fossil fuels underground. Thus, the initiative also raises a fundamental question of eco-social justice and stability of Planet Earth: leaving fossil fuels underground becomes essential to respecting the "safe and just Earth system boundaries" defined by Rockström et al. in 2023. The Yasuní-ITT initiative thus highlights the need for a transition (or rather, a transformation) that redefines the concept of global development and sustainability. Such a transformation must take into account the principles of intersectionality; intergenerational justice — both between 'past and present' and 'present and future'; intragenerational justice among individuals, communities, and nations; and interspecies justice.

From Yasunization Towards a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty

Since the Yasuní-ITT initiative, proposals for compensation in exchange for foregoing the exploitation of fossil resources have gained limited traction globally Nevertheless, some countries have voluntarily adopted extraction moratoria for environmental, climatic, social, and economic reasons (Greene and Carter, 2024).

One of the most structured proposals to carry forward the legacy of Yasunization is currently the civil society initiative for a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty. The initiative advocates the ratification, within climate governance frameworks, of a binding treaty to globally coordinate the phase-out of fossil fuels. It is founded on three key principles: non-proliferation, disarmament, and a just and peaceful transition. Non-proliferation provides for the prohibition of new concessions to extract fossil fuels, while disarmament provides for the gradual reduction of existing extraction and the closure of operating plants; finally, the third principle promotes a just transition based on cooperation between countries and at the local scale (Newell and Simms, 2020).

Although still in its early stages, the initiative has already received support from thirteen states, including Colombia, an Amazonian nation neighbouring Ecuador and one of the world's main oil producers. Around this nucleus, it is hoped that a broader consensus can be built in favour of these policies for the regulation of fossil fuels, which are nothing other than policies to ensure the protection of the planet, justice, and human rights.

To learn more

Greene, S., Carter, A. V. (2024), From national ban to global climate policy renewal: Denmark’s path to leading on oil extraction phase out. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 24(1), pp. 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-024-09625-1

Greenpeace (1997), Fossil fuels and climate protection: the carbon logic, Paesi Bassi, Amsterdam, https://www.greenpeace.to/greenpeace/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/FOSSIL-FUELS-AND-CLIMATE-PROTECTION-THE-CARBON-LOGIC-1997.pdf

Lenferna, G. A. (2018), Can we equitably manage the end of the fossil fuel era? Energy Research & Social Science, 35, pp. 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.11.007

McGlade, C., Ekins, P. (2015), The geographical distribution of fossil fuels unused when limiting global warming to 2 °C. Nature, 517(7533), pp. 187–190. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14016

Newell, P., Simms, A. (2020), Towards a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty. Climate Policy, 20(8), pp. 1043–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1636759

Rockström, J., Gupta, J., Qin, et al. (2023), Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature, 619(7968), p. 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06083-8

Welsby, D., Price, J., Pye, S., Ekins, P. (2021), Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 °C world. Nature, 597(7875), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03821-8