LGBTIQ+ Refugee: The Case of Brazilian Transgender Women in Italy

Table of Contents

- The Refugee Definition: Consolidation as a right and recognition criteria

- LGBTIQ+ refugees: the emergence of the category in the international context

- Constituent elements of persecution against transgender women in Brazil

- Conclusion

“Why are you seeking asylum? Brazil is not at war” was the question made by a public official in a health district in the Province of Vicenza to a Brazilian trans woman, one of the project’s beneficiaries in which I work, when she requested her health card, as asylum seekers are entitled to this right. It was clear that there was a misconception about the refugee definition. Migration is inherent to human nature though, and the act of migrating to safer places has always been present throughout human history. In this sense, the institution of refuge stands as a testament to humanity’s ongoing quest for justice and solidarity in the face of persecution and violence.

The Refugee Definition: Consolidation as a right and recognition criteria

In July 1951, the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees was adopted, laying the legal foundation for the modern definition of a refugee, in its Article 1A(2). According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), a refugee is someone who, owing to a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside their country of nationality and is unable or unwilling to seek its protection.

The phrase “well-founded fear of persecution” incorporates both subjective and objective elements. While fear is inherently personal, it must be supported by credible, objective circumstances to meet the legal threshold. Refugee status is thus not determined solely by an individual’s perception, but also by whether that perception is reasonable in light of the situation in their country of origin. A history of past persecution is a strong indicator, but even those who have not personally experienced harm may qualify if returning would expose them to a real risk of persecution.

Applicants must establish a fear of persecution based on one of the five protected grounds listed in the 1951 Convention. Often, individuals may not clearly identify the specific ground of persecution, but this does not invalidate their claim. Among these grounds, the term “membership of a particular social group” is deliberately open-ended. Unlike the other categories, it is not precisely defined, allowing for broader interpretation to include groups that may not have been foreseen when the Convention was drafted. As a result, it has become a vital tool in protecting individuals in changing social and legal contexts.

LGBTIQ+ refugees: the emergence of the category in the international context

In recent decades, increasing international awareness of the rights of sexual minorities, supported by the advocacy of NGOs and global actors, has led to broader recognition of LGBTIQ+ individuals as a vulnerable group. Despite the legal minority status of LGBTIQ+ people, political will to implement protective measures remains limited. In light of these persistent rights violations, legal scholars and courts in various jurisdictions have begun to support the recognition of refugee status for individuals persecuted on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

A key development in recognizing LGBTIQ+ individuals as refugees was the adoption of the Yogyakarta Principles in 2007. Though not legally binding, these principles articulate how international human rights law applies to sexual orientation and gender identity, bridging gaps between refugee law and broader human rights protections. Since their publication, UNHCR has increasingly acknowledged sexual and gender diversity in its documents. In 2012, UNHCR issued Guidelines on International Protection No. 9, which formally adopted the “LGBTI” category. The guidelines highlight that LGBTI individuals face widespread human rights violations globally, including violence, torture, arbitrary detention, and discrimination in key areas like health, education, and employment.

With regard to international law implementation, Italy, having ratified the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol, has incorporated EU directives from the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) into national legislation. This legal framework theoretically supports the protection of Brazilian trans women who can demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution.

Constituent elements of persecution against transgender women in Brazil

In Brazil, the transgender community has faced significant challenges but has also achieved important milestones in recent years. The country has a diverse and vibrant transgender population, yet this community often experiences discrimination, violence, and marginalization in various aspects of society. Despite these advancements, challenges persist.

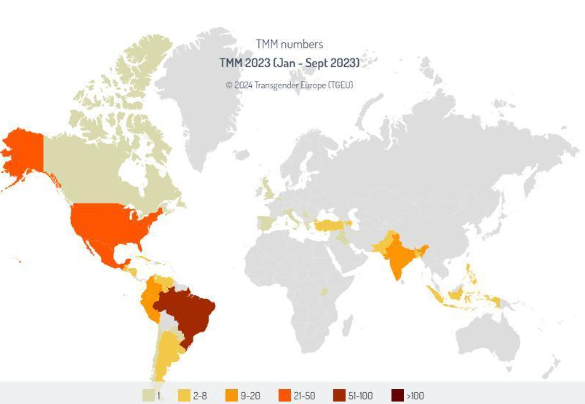

The Trans Murder Monitoring (TMM) project systematically monitors, collects and analyses reports of homicides of trans and gender-diverse people worldwide. Trans Murder Monitoring 2023 data shows that 321 trans and gender diverse people were reported murdered in all countries that have contributed to the project between 1 October 2022 and 30 September 2023 (see the map below for the period January-September 2023 – Figure 1). 94% of victims were trans women or trans feminine people and almost three-quarters (74%) of all registered murders were committed in Latin America and the Caribbean; nearly one-third (31%) of the total occurred in Brazil, which indicates that this is still considered a high-risk country for this population.

Figure 1

Map of the number of murders of trans and gender-diverse people worldwide, from January to September 2023

However, the lack of data on the transgender population also impacts the production of information regarding murders and violence stemming from transphobia. For this reason, the Trans Murder Monitoring Project emphasizes that the data presented is not comprehensive and can only provide a glimpse into a reality which is undoubtedly much worse than the numbers suggest. In Brazil, the National Association of Travestis and Trans (Antra) denounces the absence of government data on violence against the trans population as a serious problem that needs attention, affirming the urgency in understanding why the public security secretariats of Brazilian states do not adequately consolidate this information.

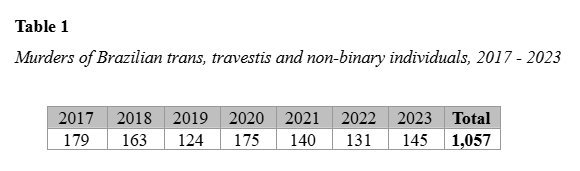

Since 2018, Antra has been responsible for one of the main publications on violence against the trans population, the Dossier on Murders and Violence against Trans People in Brazil. The table below shows the data from the last seven years, produced between 2017 and 2023 (Table 1).

The numbers in Table 1 represent an average of 151 murders per year and 13 cases per month. The 2024 dossier emphasizes that in 2023, at least 54% of the murder cases were presented with elements of cruelty, such as excessive violence, multiple blows, decapitation, and association with more than one method and other brutal forms of violence, such as dragging the body through the street and targeting blows in areas like the head, breasts, and genitals. For experts, this denotes an easily identifiable element in hate crimes, such as femicides and other crimes, revealing the presence of transphobia in these crimes.

Other findings of the research showed severe discriminations faced by this social group in Brazil. Regarding health for instance, they frequently encounter misgendering, inadequate care, and the denial of their chosen names, a symbolic and existential form of exclusion. Although public health initiatives have addressed HIV/AIDS prevention and gender-affirming care, access remains precarious and insufficient, often pushing trans women toward risky practices such as unsupervised hormone use and industrial silicone injections. These actions should not be interpreted as irresponsible behavior, but rather as forms of resistance and survival in the face of systemic healthcare failure and social marginalization. Trans women develop coping strategies – such as mobilizing personal networks within the health system and performing what they term “feminine refinement” – to navigate institutional barriers and mitigate discrimination. The concept of passing, central in Queer Studies, further illustrates how the pursuit of cisnormative appearance becomes a protective mechanism against both societal violence and intra-community marginalization. Trans women face intersecting forms of oppression, due to gender identity, class, race, and sexuality, and often suffer disproportionate levels of violence and murder in Brazil, making passing not only a social strategy but a means of physical survival.

Studies also show that transphobia drives trans people away from schools and universities. Transgender individuals are dramatically underrepresented in Brazil’s educational system: around 70% do not complete high school, and only 0.02% reach higher education, with just 0.2% of students in public universities identifying as trans (Andifes, 2019). This severe underrepresentation is not merely the result of voluntary dropout, but rather of institutional practices that systematically expel these students from school. As Luma Nogueira de Andrade argues, trans students are subjected to a “pedagogy of pain” – a process in which schools, functioning as disciplinary institutions, enforce conformity through symbolic and material violence. Common practices include refusing to use chosen names, denying access to gender-appropriate restrooms, excluding trans experiences from curricula, and punishing expressions of gender identity. Andrade outlines eight core factors that contribute to this environment, such as the lack of teacher training on gender diversity, enforcement of heteronormative norms, and barriers to full participation in school life. These conditions create a hostile environment that makes continued attendance unbearable, forcing trans students out in a process resembling unofficial expulsion.

Transgender women in Brazil are often excluded from family and school environments at a very young age, a process that initiates a cycle of systemic vulnerability marked by educational interruption, lack of financial support, and social isolation. This early exclusion frequently pushes them into survival situations such as homelessness and sex work, especially given the structural barriers they face in accessing the formal labor market. Without formal education and in the absence of inclusive hiring practices, many trans women, particularly those who are poor, Black, and expelled from home, struggle to secure stable employment, often finding prostitution as the only viable means of subsistence. Their experiences in the workplace are often marked by fear, constant vigilance, and the pressure to “prove” their worth in environments where transphobia is latent or explicit. Marinho and Silva de Almeida describe this reality as navigating a “minefield,” where the threat of humiliation or violence is ever-present. Consequently, even those who break into formal employment remain in precarious and inferior social positions, having to negotiate recognition and basic respect in spaces that rarely guarantee their rights.

Facing intersecting forms of exclusion, Brazilian trans women are significantly more vulnerable to human trafficking, particularly for the purpose of sexual exploitation. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 74% of trafficked transgender individuals between 2017 and 2020 were victims of sexual exploitation, a pattern linked to systemic discrimination, labor market exclusion, and precarious migration experiences. The marginalization of trans individuals creates a structural condition in which prostitution becomes one of the few accessible survival strategies. The Transatlantic Journeys study shows that many Brazilian trans women migrate to Europe, especially Italy, in pursuit of safety and economic opportunity, yet encounter a “dual stigma” as undocumented migrants and trans sex workers. These women are often unaware of their rights or legal protections, rendering them susceptible to deceptive recruitment practices, exploitation, and state repression. As UNODC emphasizes, trafficking is not only about force, but about vulnerability produced by deep social inequalities—particularly those shaped by gender identity, race, and class. Migration, therefore, becomes both a form of escape and a new terrain of risk, where support and exploitation frequently coexist.

Conclusion

Brazilian trans women may be considered eligible for refugee status under the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, as they belong to a particular social group that suffers systematic human rights violations, such as transphobia, exclusion from education, healthcare, and the labor market, and heightened vulnerability to violence and human trafficking. These violations may constitute persecution, at least in terms of the objective element of asylum request analysis. Although legal frameworks like the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) theoretically provide mechanisms for recognition and protection in countries such as Italy, barriers such as lack of information, trauma, and social stigma often prevent trans women from accessing these rights. Therefore, acknowledging the extreme marginalization faced by this group is essential not only for their legal protection but also for promoting their visibility and inclusion in academic and policy debates.