Advancing Human Rights and Democracy through Electoral Justice: The Case of Kenya

Table of Contents

- Electoral Justice and Human Rights Protection

- Kenya and the Critical Importance of Electoral Justice

- The Annulment of the 2017 Presidential Election

- The Impact of the 2017 Verdict on the Promotion of Human Rights and Democracy

- Conclusion

The competitive nature of democracy and elections makes the occurrence of electoral disputes a quite diffused phenomenon, in consolidated and weak democratic systems alike. Accordingly, every country aiming at reinforcing its democratic architecture should design an efficient and responsive Electoral Justice System (EJS), a broad term which refers to all the institutions and mechanisms available in a country to ensure that every aspect of the electoral process is consistent with the law and citizens’ electoral rights adequately protected. Specifically, every EJS disposes of an Electoral Dispute Resolution Body (EDRB), which is the institution - more frequently a court-mandated to settle electoral litigations.

Electoral Justice and Human Rights Protection

When it comes to implementing effective mechanisms for the protection of human rights, electoral justice emerges as one of the privileged tools to adopt. In fact, the establishment of EJSs represents a critical choice in favour of more viable democracies and towards enhanced compliance with international human rights standards on civil and political rights.

Concerning the strengthening of democracies, EDRBs perform both a corrective and preventive function: by settling electoral disputes, they also highlight specific problems of the electoral process, helping to target electoral reforms better and improve electoral management. Moreover, the efficient resolution of electoral disputes enhances people’s trust in democratic institutions, rooting a culture of legality, which is indispensable for the legitimisation of democratic governance.

Through the creation of EDRBs, States can also improve their human rights performances. The connection between human rights and electoral justice is complex and indirect. It is complicated because both the national and international levels are involved; and it is indirect because international law protects rights that, although not having exclusive relevance in the electoral context, may also emerge in electoral litigations.

Therefore, national EJSs and international human rights are not disconnected. First of all, electoral rights are a subset of civil and political rights. Fundamental human rights instruments like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights protect a right of participation in the public life of a country, which can mainly be achieved through free and fair elections. Many other human rights may emerge in cases brought before national EDRBs: the right to join a political party, freedom of expression, the principle of non-discrimination and again, the right to a fair and public hearing before an independent and impartial tribunal or the right to access information.

Secondly, the importance of electoral justice is clearly emerging at the regional level, with many international organisations acknowledging the protection of electoral rights as an essential element of democratisation processes. For instance, the preamble of the Inter-American Democratic Charter calls for a preventive effort to anticipate the problems affecting democratic governance, which is indeed an objective of EDRBs; while the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance specifically demands the ratifying countries to establish national mechanisms to redress electoral disputes (art. 17.2).

Finally, EDRBs qualify as an effective tool to realise the objectives of the Agenda 2030 and, in particular, Sustainable Development Goal n° 16 on Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions.

Despite the evident connections between electoral justice and human rights, international law does not regulate the subject in detail. Consequently, the resolution of electoral litigations is still mainly regulated by national legislation.

Kenya and the Critical Importance of Electoral Justice

Kenya represents the archetypical case study for research on electoral dispute resolution, providing all the necessary elements to assess the impact of electoral justice on democracy and human rights promotion. In fact, since the restoration of multiparty democracy in 1992, Kenya has been characterised by highly contested elections, ethnification of politics and recurrent electoral disputes.

Although Kenya has been able to regularly organise elections, all Presidential polls but 2002 have been characterised by challenges of the results and episodes of election-related violence. However, before the 2008-2010 constitutional reform process, Kenya did not dispose of an independent and reliable EJS: petitions were easily dismissed, and the judiciary perceived as a corrupt institution. Consequently, the peaceful resolution of electoral disputes was not seen as a viable option to seek justice against electoral malpractices.

Not surprisingly, in 2007 a violent post-electoral crisis affected the country for two consecutive months, bringing Kenya on the edge of uncontrolled civil conflict, institutional paralysis and economic breakdown.

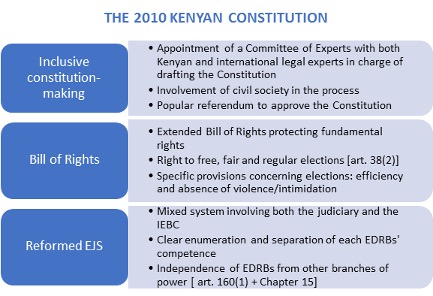

A way out of the crisis could be only found thanks to the intervention of an African Union-sponsored mediation mission, led by the former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan. The merit of the Annan’s mission was not only to convince the opposite parties to sign an agreement for the immediate cessation of the hostilities and delivery of humanitarian relief but also to commit them to power-sharing and constitutional reform. The outcome of this crisis-management effort was the adoption, after a popular referendum, of the 2010 Constitution.

The new Kenyan Constitution contributed to addressing some of the root causes of the 2007 conflict. It introduced a new “mixed” electoral dispute resolution system providing for two EDRBs with differentiated competences. While the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) settles all the disputes concerning the pre-electoral period, the different courts of the judicial system address the petitions filed after the announcement of the electoral results. In particular, the Supreme Court is now competent to hear and adjudicate disputes concerning Presidential elections. The Supreme Court is under the obligation to settle disputes concerning presidential elections within a rigid timeframe, and its decisions are not subject to appeal.

Figure 1 Kenyan Constitution 2010

The Annulment of the 2017 Presidential Election

The 2017 Presidential election marked the history of Kenyan democracy. The opposition leader Raila Odinga challenged the incumbent Uhuru Kenyatta in a repetition of the 2013 presidential race. Following a peaceful election day, Kenyatta was proclaimed the winner with a 54.2% majority. At that point, Odinga filed a petition before the Supreme Court, denouncing the failures of the electronic system for the transmission of the results and the IEBC’s incompetence inadequately supervising the tallying procedures.

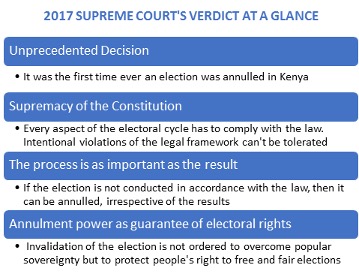

After having heard the parties into the case, Odinga as the petitioner and the IEBC and Kenyatta as the respondents, the Supreme Court of Kenya delivered an unprecedented verdict on the 1st of September 2017, annulling the August Presidential election and calling for a re-run to be held in October. The grounds for this decision was the failure, negligence or refusal by the IEBC to conduct the election in a way consistent with the constitution.

To justify its historic decision, the Supreme Court affirmed some important principles which now make up the cornerstones of its electoral jurisprudence. One above all is the acknowledgement that elections are not only about numbers, but rather they are processes; hence, every aspect of the electoral cycle, from preparations for the election day to the announcement of the results, has to comply with the constitution and applicable election laws. It does not mean that minor shortcomings cannot occur, but rather that they should never amount to a blatant and intentional violation of the legal framework.

On these grounds, and after having examined all the relevant evidence, the judges concluded that the IEBC’s negligence and failures of the electronic system for the transmission of the results had so much distanced the Presidential election from the required constitutional standards that it was necessary to invalidate it and organise a re-run.

The aftermath of the sentence was characterised by vehement attacks on the judiciary coming from Kenyatta and the ruling party, but also by civil society activism in defence of the judges and constitutional order.

Odinga’s party also contributed to rising tensions, calling for unfeasible electoral reforms and finally voluntarily withdrawing from the October re-run. As a result, Kenyatta ran uncontested, being re-elected with 98.3% of the votes.

Figure 2 2017 Supreme court's verdict at a glance

The Impact of the 2017 Verdict on the Promotion of Human Rights and Democracy

Despite the uncontested 2017 presidential re-run, the Supreme Court’s annulment verdict enormously contributed to reinforcing the Kenyan system of protection of human rights and its democratic institutions. This positive impact was achieved thanks to the principles affirmed by the Court, including that of the supremacy of the constitution and standards for the protection of electoral rights.

First of all, the 2017 sentence was the result of a completely reformed electoral justice system. It is designed through constitution-making and inspired by the principles of full accessibility, expeditiousness and transparency of the process. At the same time, it is also inspired by the principles of independence, integrity and professionalism of the adjudicators. Hence, the 2010 constitutional reform proved crucial to deliver an electoral justice system fully complying with generally accepted principles of justice and effective remedy.

Secondly, it turned out that in 2017 the Supreme Court was able to develop the principles of its electoral jurisprudence further, first sketched out in 2013 when it had dismissed Odinga’s petition and confirmed Kenyatta’s electoral victory. On the one hand, the judges confirmed their 2013 interpretation concerning the role of rejected votes in counting procedures and the standard of the proof in electoral petitions. On the other hand, they clarified the legal grounds to annul elections, highlighting that non-compliance with the law is per se sufficient to invalidate the results, irrespective of the numerical outcome. This attitude significantly enhanced the coherence and predictability of Kenyan electoral jurisprudence and, ultimately, people’s trust in the EDRB.

Another aspect to be considered is the effort made by the Supreme Court to explain that the decision to annul an election is not taken to overcome popular sovereignty, but rather to make it meaningful. In effect, the annulment power under the Kenyan constitution is neither self-attributed nor limitless: it was conferred by the people of Kenya to the Supreme Court to ensure that elections are consistent with the legal framework. For the Supreme Court, ignoring widespread irregularities would be tantamount to an abdication of its role as the guardian of the constitution as well as an unacceptable tolerance of the illegal conduct of those bodies which are mandated to guarantee the lawfulness of the electoral process.

In 2017 the Supreme Court demonstrated that it was ready to take unprecedented steps, if the conditions required it, to protect people’s right to vote and implement the content of the constitution.

One last aspect to be taken into account is the “national” character of the 2017 sentence; although the final verdict clearly lacked any reference to international human rights law, it effectively contributed to increasing Kenya’s capability to honour the international obligations it assumed concerning the protection of civil and political rights.

Conclusion

Thanks to the 2010 constitutional reforms, Kenya is nowadays equipped with an EDRB which can be promptly activated to protect people’s electoral rights, enshrined both in the Kenyan constitution and international human rights instruments.

The progress achieved by the country in electoral dispute resolution is even more striking if we consider that, under the previous constitution, the EJS could not be considered independent and transparent. Consequently, alleged electoral frauds were not even investigated, and violations of the electoral framework largely tolerated. This situation exacerbated political and ethnic tensions, fuelling uncontrolled election-related conflicts, the most violent of which broke out in 2007, causing thousands of deaths and institutional paralysis.

The 2017 Supreme Court’s sentence represented the culmination of the efforts made to endow Kenya with an institutional system able to sanction electoral malpractices, make democracy meaningful and enhance the country’s capacity to meet international human rights obligations.

The absence of references to international human rights law in the analysed sentence is indicative of the current lack of any binding international obligation concerning the resolution of electoral disputes. As long as international law will stay silent on the issue, national EDRBs can do nothing but adjudicate electoral petitions by referring to national legislation.

In order to support progressive electoral jurisprudence like Kenya’s, it is crucial to insist on the necessity to regulate further electoral justice at the international level, starting from important initiatives like the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, which has already acknowledged its importance to advance human rights and democratic governance.