The United Nations and the Rwandan genocide

Table of Contents

- The Rwandan ethnical composition and the origins of conflicts between Hutu and Tutsi

- The UNAMIR peacekeeping mission

- The UN intervention after the genocide

- Conclusion

Antonio Guterres, the United Nations Secretary-General, in a speech to the General Assembly on 12 April 2019 declared: “This year marks the 25th anniversary of the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. On this Day, we honour those who were murdered and reflect on the suffering and resilience of those who survived /…/ Today we stand in solidarity with the people of Rwanda.”

As a matter of fact, the small State located in the Eastern part of Central Africa experienced one of the worst human tragedies: the genocide of more than 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutus. The extreme violence registered in the region, led the United Nations to intervene in different stages: from a monitoring role to the establishment of a real peacekeeping mission: the UNAMIR.

Therefore, the purpose of this article is to analyse the role of the UNAMIR before, during and after the genocide, with an emphasis on the United Nations challenges and achievements. Particularly, this paper is divided into three parts: the first one briefly presents the historical steps which provoked the hatred between the two main communities: Tutsi and Hutu; the second one focuses on the UN peacekeeping mission, while the last one concerns the Rwandan reconstruction based on the values of reconciliation and solidarity.

The Rwandan ethnical composition and the origins of conflicts between Hutu and Tutsi

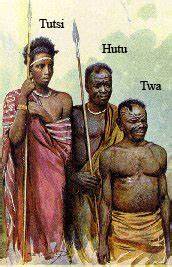

Figure 2:The three main communities in Rwanda. Twa were pygmies and short, Hutu were short and shared Bantu features, while Tutsi were taller but thinner and with more prominent bodies.

Three main communities historically composed the Rwandan population: the Twa (1%) the Tutsi (17%) and the Hutus. Despite being physically different, they had a peaceful cohabitation under a Tutsi monarchy. The European colonisers, Germans first and then the Belgians, introduced a social stratification, which considered Tutsi as “the superior race,” while Hutus were the inferior one. The Belgians created an identity card system differentiating Tutsi and Hutu, as a result, Hutus were denied rights and excluded from every dimension of life.

Discrimination and hatred against Hutus constituted the basis for the Hutu political mobilisation. As a matter of fact, they published on 24 March 1957 a document called “Notes on the social problem of racial indigenous in Rwanda” also known as the “Bahutu Manifesto”, which declared the Hutu ideology and denounced the Tutsi monarchy. In 1961, at the end of a Hutu social revolution that killed around 20,000 Tutsi, the Hutu party (Parti du Mouvement de l’Emancipation Hutu - MRD-PARMEHUTU) established a government based on the Bahutu Manifesto ideals.

When Rwanda became Independent on 1 July 1962, Gregoire Kayibanda was elected as the first Hutu President, and he promoted an anti-Tutsi government. Notwithstanding this, Kayibanda was replaced with a coup d’état in July 1973 by the officer Juvenal Habyarimana ; Habyarimana transformed Rwanda into a totalitarian regime ruled by a single party: the Mouvement Révolutionnaire National pour le Développement (MRND). The common point between Kayibanda and Habyarimana remained the elimination of Tutsi who, as a consequence, were forced to find refuge in neighbouring states, where they founded the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) a paramilitary organisation.

The invasion of the RPF into Rwanda, on 1 October 1990, provoked a civil war between Hutu and Tutsi. On 4 August 1993, the two parties signed the Arusha Peace Agreements under the supervision of the International Community. Those Accords paved the way for the institution of a Broad-Based Transitional government with both Hutus and Tutsis’ representatives, but especially it gave life to the United Nations Mission Assistance to Rwanda.

Nonetheless, this apparent diplomatic victory collapsed on 6April 1994: President Habyarimana died in a plane crash after a visit to Tanzania and genocidal massacres, incited by Radio Télévision Libre Des Milles Collines (RTLMC) and the Kangura newspaper, exploded in the country against the Tutsis.

The UNAMIR peacekeeping mission

Figure 3: Romeo Dallaire, a Canadiar army officer and Force Commander of the UNAMIR peacekeeping mission in Rwanda.

The presence of the United Nations in Rwanda commenced before the outbreak of the genocide: as a matter of fact, on 22 June 1993 the Security Council introduced the United Nations Observer Mission Uganda-Rwanda (Resolution 846), with the purpose of controlling weapons’ transportation between the borders of Uganda and Rwanda for six months. When the civil war erupted throughout Rwanda, the Arusha ceasefire agreements were fundamental to terminate the conflict; and on that occasion the United Nations endorsed the peacekeeping operation UNAMIR with Resolution 872. The aim of UNAMIR was to contribute to keeping the security of the capital Kigali, monitor the cease-fire agreement and to observe the transitional government’s mandate. UNAMIR was doomed to fail due to a range of factors: first, the UNAMIR mandate was too broad, and the Security Council could not provide Force Commander Dallaire with enough resources. Despite Dallaire's request of 4,500 troops, the Security Council could cover the costs for only 2,560 soldiers. Besides, the mission was installed under Chapter VI of the Charter, and, for instance, it did not allow the use of force during the operations.

In addition, the Security Council misinterpreted the Arusha Accords, and it reduced the UNAMIR tasks to guarantee security in the territory. The serious challenge was the incapacity to communicate between Force Commander Dallaire and the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO). The episode of the “genocide fax”was a clear sign of weakness of the DPKO; indeed, on 10 January 1994, Dallaire, during a secret meeting with the Provisional Prime Minister of Rwanda, discovered by a person belonging to the MRND the planning of a campaign to eliminate the Tutsi. Dallaire immediately informed the DPKO with a fax on 11 January 1994, but the DPKO denied the call for action. As a matter of fact, after receiving the genocide fax, the Under Secretary-General Kofi Annan and the Assistant of the Secretary-General, Iqbal Riza, doubted about the credibility of the fax’s information, and considered it as “a cause of concern but full of inconsistencies”. Besides, the aim of the peacekeeping cable was to ban every use of force and to prevent Dallaire from every intervention in Rwanda, despite genocide’s threats. In the end, the cable answered only to the United Nations special representative for Rwanda, Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh and not to Dallaire and as a result, Booh-Booh respected the UN peacekeeping department’s orders, ignoring the increasing risk for Tutsi.

On 5 April 1994, the Security Council approved Resolution 909 to set up a transitional government, following Arusha Accords, but the day after, at 8.23 President Habyarimana was killed and massacres exploded. The UNAMIR collapse continued until 21 April 1994: the Security Council voted Resolution 912 for the withdrawal of most peacekeepers with a symbolic presence of 270 soldiers. At the end, it was only under the pressure of the new Secretary-General Boutros Boutros Ghali that, on 17 May 1994, the Security Council voted for Resolution 918 to install 5,500 army troops for humanitarian assistance in Rwanda.

The UN intervention after the genocide

On 4 July 1994, the Rwandan Patriotic Front conquered Kigali and on 18 July 1994 declared its victory. The new government dealt with the post-genocide situation and focused on reconstruction and reconciliation. Accountability for genocide crimes and a new judicial system constituted the basis to end the culture of impunity and to bring faith in the RPF institutions.

Despite the RPF efforts to set up special legal procedures to perpetrate the crime of genocide, such as the Domestic Criminal Prosecutions and Gacaca courts, Rwanda needed an international presence to guarantee a fair and impartial judicial system.

Figure 4: Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (third from left, front row) poses for a group photo with the judges of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR).

Therefore, the Security Council, answering the request of the Secretary General, endorsed Resolution 935, instituting a commission of experts to investigate human rights violations in Rwanda. On 8 November 1994, the United Nations unanimously approved the war crime tribunal and inaugurated the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). According to the Security Council, the ICTR was established under Chapter VII of the Charter, based on peace and security objectives. The ICTR condemned acts of genocide, crimes against humanity and for the first time in history international law denounced rape and sexual violence as crime against humanity.

In addition, the United Nations had to deal with the refugee crisis, the educational field, and the economic reconstruction.

As far as concern the refugee situation, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) introduced a repatriation plan centred on implementing areas of return for old-case refugees (people who left the country in 1959 and came home in 1994), providing minimum rehabilitation, and coordinating with local authorities in the area.

Besides, the United Nations Rwanda Emergency Officer (UNREO) cooperated with the UNHCR to reinforce the security of returnees and to guarantee the repatriation of internally displaced persons with registration centres, food and medicine supplies. On 22 June 1994, the Security Council adopted Resolution 929 on the French initiative that generated Humanitarian Safe Zones in the Cyangugu-Kibuye-Gikongoro triangle in South-West Rwanda with humanitarian purposes, and particularly, to protect internally displaced persons, refugees and civilians in Rwanda.

Furthermore, regarding the educational field, UNESCO and UNICEF introduced the Teacher Emergency Packages (TED). These programmes consisted of mobile classrooms to furnish students psychological assistance and minimum educational services until the restoration of a new education system. On the other hand, the economic reconstruction viewed a cooperation between the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Food Programme. Hence, they installed programmes called “seeds and tools” to favour economic agricultural rehabilitation, while the International Agriculture Research Centre (IARC) developed the initiative “seeds of hope,” whose goal was to distribute seeds of bean, maize, potato and sorghum to Rwanda, within the Rwanda Recovery Plan.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Rwandan genocide was the result of several factors and episodes that involved the United Nations. The International Community admitted its responsibility during massive killings, but since that moment, the United Nations intervened to offer humanitarian assistance and to protect innocent victims.

On 7 April 2004, the UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan in a speech to the Commission of Human Rights, acknowledged the United Nations responsibility in the Rwandan massacres, but he also introduced an Action Plan to prevent genocide for the future. The Action Plan was composed of five points: preventing armed conflict, the protection of civilians in armed conflict, ending impunity, early and clear warning and in the end the need for decisive action in case genocide was happening or it was about to happen.

The Rwandan genocide demonstrated how the responsibility to prevent, must always be accompanied by the responsibility to protect and the United Nations must take all necessary measures to avoid escalation of violence and to guarantee civilian protection in the future.