Challenging the Securitization of Migration in Italy: A De-securitization Strategy

Table of Contents

Introduction

Since 1975, year corresponding to the turning of Italy into a country of immigration, the Italian border and migration management appears rooted in the migration-security nexus. Discursive and non-discursive practices performed by the Italian political élite have shifted migration from a non-political topic, to a political one, to a security issue. However, is securitization of migration desirable? What are its human rights implications and spill over effects? After reconstructing the Italian securitization process and providing an overview of its main consequences, this article proposes a disarticulation of the migration-security nexus through the development of a de-securitization strategy suitable for the Italian context.

The securitization of migration and border management in Italy

Drawing on critical security studies, securitization is a process consisting in the movement of one issue, in this case migration, in the realm of security: migration is presented as an existential threat requiring emergency measures and justifying actions outside the normal bounds of political procedures. Looking at the Italian context, since Law 39/1990, the first legislative attempt to regulate migration, securitization has been successfully performed through speech acts, such as statements, political documents, and practices, such as border processes and integration policies, enacted by the so-called securitizing actors – the Italian governmental élite – and facilitated by other functional actors – mass media, law enforcement agencies, lobby, and private actors. A historical analysis of these discursive and non-discursive securitizing practices reveals that the Italian border and migration management is structured along three main axes: emergency, security, and criminality. The emergency narrative, exemplified by the recurring evocation of the siege metaphor and recourse to the lexicon of the invasion – i.e.: the slogan of the current Minister of Agriculture, F. Lollobrigida, on “ethnic substitution” – has been coupled by the decision to favour Decree-Laws as the legal source suitable for regulating migration, the iterative declaration of the “state of emergency”, and the adoption and institutionalization of extraordinary measures. These include the 2015 hotspot approach and externalization policies: from the 2008 Berlusconi-Gaddafi agreement to the 2023 Italy-Albania Protocol.

Regarding instead security, the 2009 “safety package”, converted into Law 94/2009, institutionalized the binomial “public security – migration”, by prescribing, inter alia, the punishable ex officio crime of illegal stay or the aggravated clandestine status for crimes committed by sans papiers. Accordingly, direct links between discourses on governing migration and discourses on security were established. This discursive securitization has also been coupled with practices such as the hardening of border police and surveillance technology in border controls, the storage of immigrants’ biometric data in the AFIS police database, the normalization of administrative detention, which employs a typical instrument of criminal law: the deprivation of liberty, and military transnational cooperation, as the military sphere amplifies the perception of the threat. This inevitably leads to the third axis of the Italian migration governance: the criminalization of migrants, irregular entries and search and rescue activities (SAR) performed by actors of the solidarity sector.

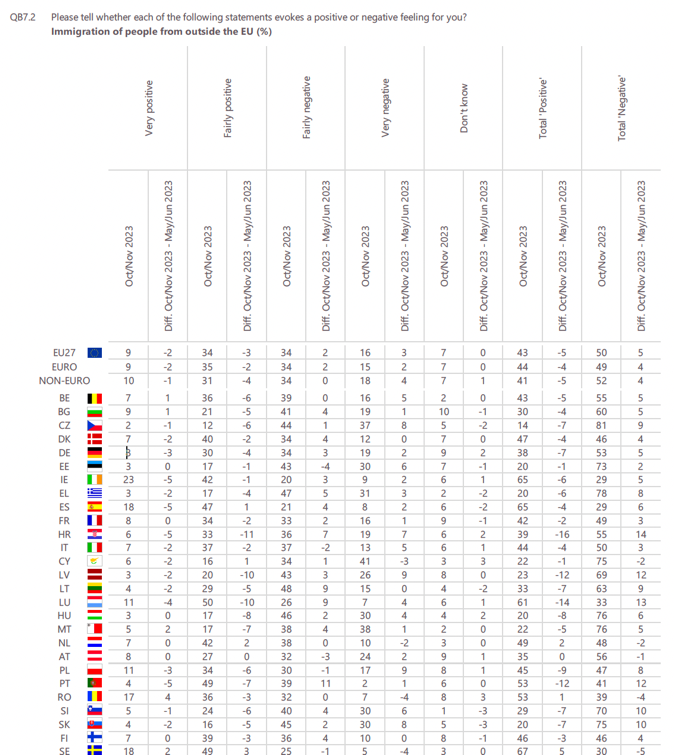

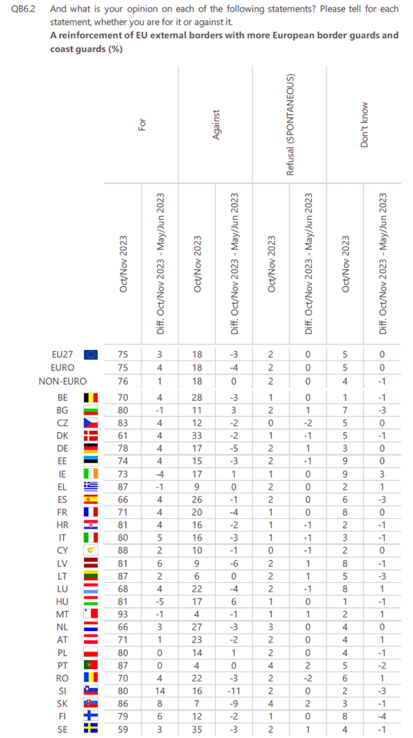

Consequently, migration appears as a “central dimension of a rounded security agenda”. However, to assess the success of securitization, it is necessary to consider its acceptance by the audience – the Italian population – because this process has an intersubjective nature. According to the latest Standard Eurobarometer on public opinion in the European Union, published in Autumn 2023, in Italy, 63% of the surveyed perceive migration as “total negative” or “very negative” and 80% are in favour of a reinforcement of EU borders.

Figure n° 1: “Public opinion in the European Union, Autumn”, QB7.2, QB6,2, source: Standard Eurobarometer 100

It is therefore clear that the presence of immigrants causes feelings of fear among Italian citizens. The binary opposition, in Schmittian terms, between the friend – citizens – and the enemy or even hostis, the absolute enemy, – immigrants – is radicalized.

However, the acceptance of securitization is not absolute. There exist both spontaneous and more organized grassroot counter discourses and practices – i.e.: NGOs advocacy actions – as well as top-down ones – i.e.: judicial bodies’ rulings or UN treaty-bodies’ recommendations. These challenge the securitization process and draw attention on its drawbacks, particularly in terms of its compliance with human rights law.

The drawbacks of securitization

Despite the institutionalized nexus between migration and security concerns, such as criminality, cultural alienation anxiety, and imbalances in the socio-demographic equilibrium, its immutability and desirability are increasingly being questioned by the aforementioned counter-movements, which reveal immigrants’ levels of vulnerability, challenges posed to integration and naturalization, and other spill over effects such as the rise of radicalization and political extremism. Both the “process” of securitization and the “outcome” rise concerns. In fact, the recourse to the realm of exception undermines liberal parliamentarism and democracy, as government’s openness and accountability decrease due to minimal and accelerated deliberation. Regarding the “outcome”, that is the production of the ‘enemy’, securitization fuels further xenophobic and racist rhetoric, while fostering practices of social exclusion and welfare chauvinism.

From a more pragmatic perspective, securitization entails major human rights violations throughout the entire migratory journey: from border-crossing to naturalization. At the Italian external borders, securitizing practices co-produce migrants’ vulnerability, entrapping them in a condition of human insecurity. According to UNHCR, in 2023, out of 150,000 people disembarked in Italy, 2000 are dead or missing. Those who do reach Italian shores are constrained in a state of “rescue without protection”: rejected asylum seekers remain stuck in irregularity or are returned, following patterns of “mobility in and towards insecurity”, and pending asylum seekers liger in a limbo of “immobility in insecurity”. This is evidenced by legal cases such as J.A. and others v. Italy (application 21329/2018) or ruling 4557/2024 of the Italian Court of Cassation. At Italian borders, indirect refoulements, arbitrary deprivation of liberty, inhuman or degrading treatments and collective expulsions of aliens are not an exception.

Negative consequences of securitizing discourses and practices materialize also in subsequent stages of the migratory journey, often undermining migrants’ enjoyment of second-generation rights. Even though, according to Istat, in 2024, the incidence of resident population with foreign citizenship reaches 9%, Italy remains one of the EU member states with the most restrictive citizenship law. The non-ratification of the European Convention on Nationality ETS 166/1997, the selective requirements to naturalization prescribed by Law 91/1992, amended by Law 132/2018, and the absence of a self-standing integration law and periodic evaluation of integration policies impose racial exclusion mechanisms. As a result, migrants are de-politicized, excluded from the receiving country’s social and political life, and relegated to the status of permanent outsiders.

De-securitization: theoretical framework

The drawbacks of securitization symptomatize the need to explore and promote alternatives, attempting to reintegrate migration into the political sphere and to dismantle the friend-enemy dichotomy. Accordingly, de-securitization – the returning of issues from ‘emergency politics’ to ‘normal politics’, the reverse of securitization – becomes crucial. A de-securitized migration and border management would not only mitigate, and potentially end, state violence against international migrants, but also offer the opportunity “to re-order the domestic in a more just way”.

Among the different declinations of de-securitization, in terms of process and agency, a de-constructivist approach should be prioritized first and foremost. Secondly, at least at an early-stage, de-securitization should be oriented to the local level, since the ‘local’ is where relations between communities are renegotiated reciprocally. What follows is a necessary determination of the agents responsible for initiating and leading the process. To avoid the reproduction of hegemonic structures, the agents of this inverse process should steam from the securitized subjects themselves. Migrants should play this role, because if it were performed by the governmental élite, they would continue to be the object of top-down policies, rather than autonomous political subjects. Accordingly, the elaboration of an optimal de-securitization strategy should draw on approaches like the autonomy of migration one, thus imposing the refusal of the methodological nationalism which is often intrinsic to the study of migration dynamics. Following M. Foucault’s insurrection of subjugated knowledges, migrants’ subjectivity should be requalified to destabilize and weaken the ‘security truth’ upheld by securitizing actors. Therefore, migrants should be recognized as agents of political transformation, with the potential to influence the ‘belonging’. Successively, they should be re-identified in a rights-entitled category, providing them with the required political statusto engage with securitizing actors in deliberative processes, penetrating them. Indeed, the success of this new paradigm depends on tangible changes in the policies and structures upholding securitization. Therefore, migrants' counter-movements should be followed by rhetorical initiatives and political actions promoted by securitizing actors themselves.

De-securitization: domains of action

Regarding the application of the previously outlined theoretical framework, two domains of action can be identified to achieve a de-securitized migration and border management: the restoration of human security in border processes and the enhancement of intercultural integration. Although related to two different stages of the migratory journey, both aim to re-articulate the border: the physical one and the one which materializes in mechanisms of social exclusion.

Concerning the first field of action, given the inverse proportionality between border security and human security, along with the exposure of migrants to the non-democratic conditions of borders, Italian border management should be reshaped through the acknowledgment and promotion of humanitarian and political borderwork carried out by NGOs and CSOs. Both grassroots actions – such as supporting unauthorized movements of people or monitoring activities – demonstrate a clear de-securitizing potential. By adopting a human rights-based approach, these practices address the humanitarian vacuums characterizing Italian border processes and raise awareness on their deficiencies, thereby constructing a bulwark against systemic exclusionary practices performed by governmental authorities. They bring migration-related issues into public debate, re-politicizing them with the goal of advocating for and lobbying towards transforming the border regime. To achieve this goal, the current border management should be recast, conceiving the free movement of people as a universal human right and adopting an open border approach, with only justified restrictions. Besides ending the discursive securitization of migration, measures should be taken to de-securitize the Italian reception system and asylum procedures. Among them: FRONTEX should be abolished, detention practices in remote centres, hotspots, or CAS as a method of reception should end, specific training programmes for officers – including modules on human rights and on legal provisions against racial discrimination – should be implemented, and accelerated border procedures and the safe third countries list should be abolished.

Shifting the focus to the second field of action, intercultural integration shows clear de-securitizing potential. Grounded on a conception of diversity as an asset and on the fact that interculturalism is a driver of inclusion, pursuant to the Council of Europe CM/REC(2015), intercultural integration contributes to the recognition of migrants as part of the ‘belonging’. It acknowledges their acts of resistance – immigrants’ self-organizations, occasional protests, and organized mobilizations – as analytics of power and catalyst of social transformation. These collective resistance actions, along with contestation and solidarity ones, are defined by scholars E. F. Isin and G. M. Nielsen as ‘acts of citizenship’: self-constructions of subjects as citizens. Through these recognition struggles, migrants who are excluded from what Hannah Arendt calls the “right to have rights” – formal citizenship – exercise their rights through citizenship practices, advancing the de-securitization process.

Therefore, promoting intercultural integration policies appears crucial. To this end, an analysis of the Intercultural Cities Index and the Italian Migrant Integration Policy Index suggests prioritizing actions focusing on migrants' socio-political participation in the host community. This not only aligns with Objective 16 of the Global Compact for Migration, but also shifts the migration discourse from a ‘threat-defence’ sequence into the ordinary public sphere. Accordingly, improvements to the current Italian framework should concentrate on two areas: informal forms of political participation – recognizing migrants’ agency and the value of cultural diversity – and formal forms of political participation – facilitating the access to naturalization and active and passive electoral rights.

However, such actions, along with those aimed at increasing human security in border processes, remain only a first step to de-securitize border and migration management in Italy. Many other efforts have to be undertaken, and the work of the new European Parliament will be decisive in this regard.