Citizenship Revocation as Punishment and the Abandoned Women and Children of IS

Table of Contents

- The Foreign Fighter Phenomenon and the Women and Children of IS

- Citizenship Revocation as a Response to Terrorist Threat

- The Case of Shamima Begum

- What the Law Says

- Conclusions

After years of declining influence and dwindling territory, in early 2019 the last remaining stronghold of the Islamic State (IS) fell, arguably marking the end of their proclaimed ‘caliphate’. As opposing forces advanced, tens of thousands of IS affiliates from a plethora of nations emerged, amongst them many women and children. Over one year on, the vast majority of countries have not yet made significant attempts to deal with their IS-affiliated nationals, and many remain in squalid, insecure camps in Northern Syria with an uncertain future. While there exists no international consensus on how best to deal with this crisis, some countries have taken the controversial steps of depriving their former nationals of their citizenship, with the UK leading the way in this regard.

The Foreign Fighter Phenomenon and the Women and Children of IS

Beginning as an affiliate of the notorious organisation Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State as an independent extremist body rose to prominence in 2014 as it increased military operations in Iraq and Syria, taking control of large swathes of territory in what would come to be known as the ‘caliphate’. The severity of the threat of IS was increased due to recruitment tactics and an international appeal never seen before. The group has been noted for its use of social media and file-sharing platforms in the recruitment process as well as the successful dissemination of its message and ideology to a global audience. The propaganda is argued to have been targeted at foreign nationals, with messages released first in English, French, and German, and later translated into languages such as Urdu, Indonesian and Russian, languages spoken in countries where groups may have traditionally looked to garner support. Converts to Islam also account for a disproportionate number of foreign fighters.

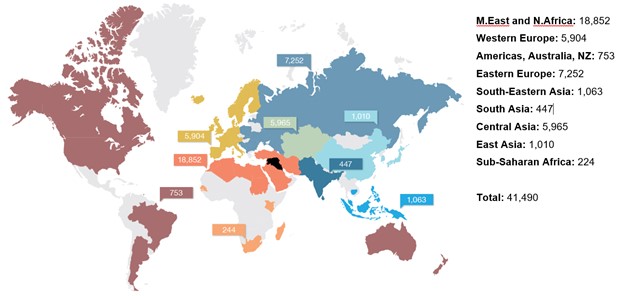

Figure 1: IS affiliates by region

Furthermore, the recruitment drive was not merely aimed at establishing a military component, but rather more broadly in establishing an attractive new society with all the various familial roles implied therein. Such campaigns had unprecedented success with social networks serving as an important tool, linking existing women of IS and potential female recruits in the telling of their stories. Though the ascription of the popular term ‘bride’ denotes a relatively passive role, it has been argued that many women were trained in the use of weapons and can also take other prominent roles in IS operations. Recruits included families with women and minors, added to by the fact that many of the women married and gave birth soon after arriving in Syria or Iraq.

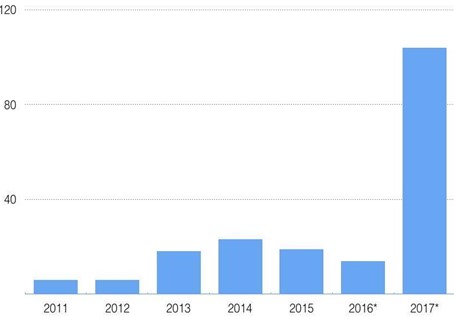

Figure 2: Women and Children of IS

Following the demise of the Caliphate, the responsibility for the fighters and their families fell largely to the Kurdish forces. Fighters were housed in make-shift jails and detention camps were constructed for the families. A United Nations report in April 2019 estimated that the main camp of Al-Hol held 75,000 people, of which 15% were foreigners and, astonishingly, 90% were women and children. More recent figures put the overall number of Europeans detained at a minimum of 1,200; mainly young children, with the majority of adults being women.

The UK and Denmark are amongst those who have opted to remove the citizenship of these fighters and of their families, with Germany and Sweden considering similar plans. Some German and French nationals have been transferred to Iraq for prosecution, a highly worrying course of action considering that recent Iraqi trials of foreigners have resulted in sentences including death by hanging. Though the repatriation of children is considered a viable option by most European governments, in reality, this has not transpired on any notable scale with the UK, Germany and France repatriating only a small number of children.

Citizenship Revocation as a Response to Terrorist Threat

Whilst by no means a new phenomenon, the act of depriving a citizen of their nationality, or denationalisation, has taken on a new relevance with the advent and demise of IS. Citizenship revocation occurs when governments, or in the case of the UK, the Home Secretary alone, make the decision that an individual should no longer hold their status as a citizen of their former country. Involuntary citizenship revocation is usually done in the name of national interests, though specificities differ from country to country. In fact, the UK has introduced three major amendments to legislation concerning citizenship revocation since 2002, each time broadening the conditions stipulating under what circumstances citizenship could be deprived and each time arguably in response to a perceived terrorist threat.

The September 11th terrorist attacks acted as a proximate cause for the first change. The government restated their denationalisation powers, uncoincidentally coming into force at a similar time to the state’s frustration at being unable to expel an undesirable radical cleric, Abu Hamza. The second in 2006, occurred subsequent to the London underground bombings of the previous year, and in order to revoke the British citizenship claimed by an Australian detainee in Guantanamo Bay, David Hicks. The 2014 amendment, which must be read in the context of the time of a surge of British citizens leaving for Syria and Iraq, resulted in denationalisation laws arguably broader than those possessed by any other Western democratic state. In a post 9/11 security landscape, it could be seen to serve governments to posit the terrorist, in particular the Muslim terrorist, as the ultimate enemy of the state. This targeted ostracism, no clearer evidenced than in the purposeful manipulation of UK policy, and mirrored in the exponential increase in the use of denationalisation powers in the years IS were active, could act to assuage public anxiety about security.

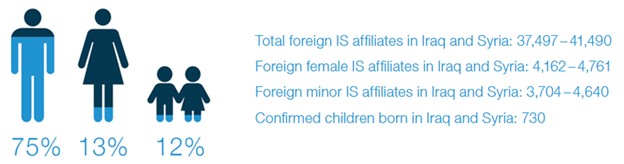

Figure 3: Number of Citizenship Revocation Orders in the UK: 2011 - 2017 (Twitter Source: @freemovementlaw)

The figures represented in this graph include only those cases where citizenship had been revoked under the broad standard that conduct was deemed ‘not conducive to the public good’. In 2017, the powers were used 104 times, with figures for the years following difficult to come by as the process is largely shrouded in secrecy.

The Case of Shamima Begum

A particularly high profile case is that of Shamima Begum, a British woman who left her home in London in 2015 to join the Islamic State. In February 2019, she was found heavily pregnant in the Al-Hol camp in Northern Syria where it was discovered that she had married a Dutch fighter and given birth to two children, both of whom had subsequently died. The case hit news headlines and a few days later the Home Secretary Sajid Javid issued a letter notifying Begum of his intent to revoke her British citizenship. This order meant that Begum would be unable to reenter the UK, obtain a British passport or receive any assistance to leave the detention facility. Her new-born son died a few days later. The British government’s justification of the legality of the order was that as Begum’s mother was in possession of Bangladeshi citizenship, she would theoretically be able to obtain an alternative nationality, and as a result not be left stateless. As per British law, the decision was effective immediately, though she was able to launch an appeal.

What the Law Says

If we accept that citizenship and nationality are all but synonymous in the eyes of the law, it becomes more difficult to defend the oft-repeated maxim that citizenship is a privilege (and thus revocable), yet conversely that nationality is a right. While citizenship revocation is not expressly against international law per se, the right to nationality and to not be arbitrarily deprived of nationality are enshrined in many documents and thus worthy of consideration. There are also additional protections afforded to women and to children in the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child respectively, that may strengthen Begum’s right, as well as applying to similar cases concerning the women and children of IS. Additionally, states have strong commitments to avoiding and preventing statelessness. In this case, although theoretically Begum would be entitled to Bangladeshi citizenship by descent, the Bangladeshi government claimed there was no question of her being allowed into the country and even stated she would be at risk of being hanged. In February 2020, the Appeals Court unanimously rejected the first stage of her appeal, setting a dangerous precedent.

Conclusions

Though the practice of citizenship revocation teeters precariously on the borders of international law, there are several important considerations to be taken into account. Firstly, in failing to accept responsibility for their former citizens, not only do states fail to acknowledge their societal role in the raising of potentially dangerous individuals, but they also miss out on a crucial opportunity to potentially detect some of the underlying root causes of radicalisation. It should also be noted that in a world where every human being must exist in one state or another, the act of expelling an individual from one territory, automatically necessitates their presence in another. Such offloading of responsibility is neither conducive to constructive international cooperation, nor does it assist in the global fight against terrorism. In fact, tarring such a broad range of Muslims with the ‘terrorist’ brush may only serve to stir up divisions and tensions between communities, perpetuating the threat of radicalisation.

Tracing the origins of the UK’s prolific use of citizenship revocation as punishment, it becomes evident it has been explicitly tailored to deal with terrorism and its affiliates. Considering its dubious basis in law, questionable efficacy and the strong grounds for objection on the basis of human rights, it should be concluded that the practice is not fit for purpose. While the most extreme forms of punishment should be reserved for the most extreme offenders, subjecting women and children to the harsh realities of this practice, is not a decision that should be made lightly or indeed frequently as has been done in the UK.