“DEPENDS!”: A Prevention Programme On Substance And Non-Substance Addictions In Lower And Upper Secondary Schools

The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey, conducted in 2024 by the World Health Organisation (WHO) across 44 countries, confirmed that substance use is highly prevalent among younger generations. Alcohol was found to be the most widely used substance, while e-cigarettes have become increasingly popular since the age of 13. The Italian context mirrors the global picture. According to data from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD), carried out in 2024 by the Institute of Clinical Physiology of the National Research Council (IFC-CNR) with adolescents in 37 European countries, 23% of Italian adolescents use tobacco, 32% use e-cigarettes, and 53% consume alcohol. Recent studies (e.g., Primi et al., 2024) have also shown that mobile phone use is extremely widespread among Italian youth, especially for instant messaging and social networking.

The use of substances such as alcohol and tobacco represents a risk factor for the development of problematic behaviours that may lead to forms of addiction, that is, behavioural patterns where control over use is gradually lost. However, problematic and dysregulated behaviours can also emerge in the absence of substances, as in the case of excessive mobile phone use, which poses a threat to adolescents (Richter et al., 2022). Young people are particularly at risk of developing problematic smartphone use, defined as escalating, excessive, and uncontrolled use that can cause personal, social, and academic problems (Billieux et al., 2015).

It is therefore essential to design, implement, and evaluate prevention programmes addressing both substance and non-substance addictions from lower secondary school onwards. In response, the project “DEPENDS! Prevention of Addictions in Pre-Adolescence and Adolescence” was developed. In 2023, it was selected through the public call issued by the Department for Anti-Drug Policies of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, aimed at funding experimental projects of national relevance and impact in the field of prevention and counteraction of behavioural and substance addictions in younger generations. Starting from the assumption that both substance and non-substance addictions are characterised by a set of common risk and protective factors (Alavi et al., 2012), the objective of “DEPENDS!” was to act on two fundamental aspects implicated in the development of addictive behaviours in adolescence: impulsivity and self-control. But what do we mean by impulsivity and self-control?

Impulsivity is a broad psychological construct reflecting various behaviours and processes, such as a present-oriented disposition, a reduced ability to delay gratification, strong behavioural disinhibition, and deficits in planning and decision-making (Evenden, 1999). Self-control, by contrast, refers to the ability to modify or override instinctive and impulsive responses, refraining from acting on them and reformulating them into different outcomes (Tangney et al., 2004). It also involves the ability to consciously direct one’s actions by controlling automatic habits (Baumeister et al., 2007). High self-control is expressed through effective motivation and persistence in pursuing goals, proactive regulation of actions, flexibility, and adjustment in task execution (Cudo et al., 2020).

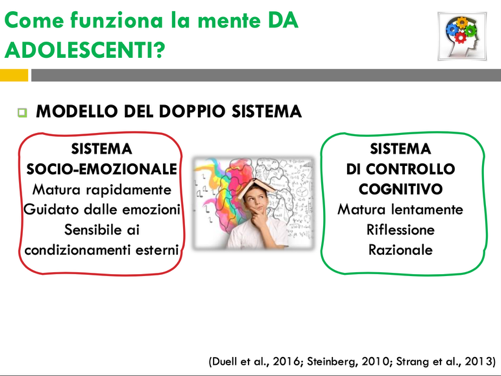

Impulsivity and self-control represent, respectively, risk and protective factors for addictive behaviours at all ages, but are particularly relevant during adolescence. According to the dual-system model of risk-taking (Somerville et al., 2010; Steinberg, 2010), at the neurobiological level, impulsivity and self-control in adolescents reflect the activity of two distinct brain systems: the cognitive system and the affective system. The cognitive system underlies deliberate processing, which is conscious and controlled, while the affective system is responsible for spontaneous and automatic processing, operating according to principles of similarity and contiguity. Because of the relative immaturity of the cognitive system and the greater maturational development of brain areas related to the affective system, adolescence represents a developmental period marked by an imbalance between the two, rendering adolescents particularly vulnerable to impulsivity (Somerville et al., 2010) and risky decisions (Chein et al., 2011). This vulnerability stems from the competition between the two systems, with the affective system being phylogenetically more mature.

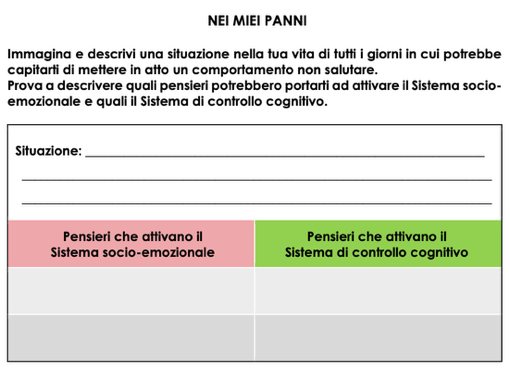

In light of these premises, the intervention sought to raise students’ awareness of the mechanisms underlying the development and maintenance of alcohol, tobacco, and mobile phone addictions, aiming to reduce impulsivity and enhance self-control. Specifically, trained psychologists guided students through activities designed to explain how the adolescent brain functions, illustrating real-life situations where the affective system is more vulnerable and more easily activated than the cognitive system (e.g., a party where drinking and smoking take place), while teaching strategies and skills to regulate behaviour. The conceptual change model (Posner et al., 1982) was adopted as the educational approach. This model has proved effective in the prevention of problematic gambling (Donati et al., 2014; Donati et al., 2018) and in the prevention of problematic smartphone use (Donati et al., 2025) among young people. The programme was developed by a multidisciplinary team of psychologists conducting research in the fields of clinical and psychometric psychology. The activities required a total of six hours, delivered across four weekly sessions (1 hour, 2 hours, 2 hours, 1 hour), and took place during school time using PowerPoint slides and printed workbooks. Both individual and group activities were included.

Six schools (three lower and three upper secondary schools) in Tuscany, specifically in the province of Florence, participated in “DEPENDS!”, involving 39 classes in total. The participating classes were in the third year of lower secondary school and the first two years of upper secondary school. To assess the effectiveness of the intervention, classes were randomly assigned to an experimental group (20 classes – 8 lower secondary and 12 upper secondary) and a control group (19 classes – 8 lower secondary and 11 upper secondary). The experimental group took part in the programme, while the control group continued regular school activities. Both groups completed pre- and post-test sessions in which impulsivity and self-control were measured through validated self-report psychometric tools for Italian adolescents.

The results showed a significant effect of the intervention in reducing impulsivity and increasing self-control. This effect held when controlling for gender. As for school level, the effect on impulsivity was found only among lower secondary school students, but not in upper secondary, whereas the effect on self-control emerged independently of school level. This finding may be explained by the fact that older adolescents may have less neural plasticity (Casey et al., 2008) as well as more extensive risk-taking experiences, which may hinder cognitive control over the affective system.

Overall, the results of “DEPENDS!” are promising and far-reaching, considering that impulsivity is a risk factor for a variety of behavioural problems in adolescence, such as aggression and antisociality; that self-control is associated with many positive outcomes in academic and health domains; and that both impulsivity and self-control are regarded as relatively stable psychological characteristics, and thus difficult to modify.

Bibliography

Gruppo ESPAD, 2025. Key findings from the 2024 European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD) [Risultati principali del progetto europeo di indagini scolastiche sull’alcol e altre droghe (ESPAD) del 2024], Agenzia dell’Unione europea sulle droghe, Lisbona, https://www.euda.europa.eu/publications/data-factsheets/espad-2024-key-findings_en

Alavi, S. S., Ferdosi, M., Jannatifard, F., Eslami, M., Alaghemandan, H., & Setare, M. (2012). Behavioral addiction versus substance addiction: Correspondence of psychiatric and psychological views. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 3(4), 290-294. Baumeister et al., 2007

Billieux, J., Maurage, P., Lopez-Fernandez, O., Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 156-162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y

Casey, B. J., Getz, S., & Galvan, A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Developmental Review, 28(1), 62-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.003

Chein, J., Albert, D., O’Brien, L., Uckert, K., & Steinberg, L. (2011). Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Developmental Science, 14(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035.x

Cudo, A., Misiuro, T., Griffiths, M. D., & Torój, M. (2020). The relationship between problematic video gaming, problematic Facebook use, and self-control dimensions among female and male gamers. Advances in Cognitive Psychology, 16(3), 248-267. https://doi.org/10.5709/acp-0301-1

Donati, M. A., Primi, C., & Chiesi, F. (2014). Prevention of problematic gambling behavior among adolescents: Testing the efficacy of an integrative intervention. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(4), 803-818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-013-9398-1

Donati, M. A., Chiesi, F., Iozzi, A., Manfredi, A., Fagni, F., & Primi, C. (2018). Gambling-related distortions and problem gambling in adolescents: A model to explain mechanisms and develop interventions. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2243. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02243

Donati, M. A., Padovani, M., Iozzi, A., & Primi, C. (2025). Prevention of problematic smartphone use among adolescents: A preliminary study to investigate the efficacy of an intervention based on the metacognitive model. Addictive Behaviors, 166, 108332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2025.108332

Evenden, J. L. (1999). Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology, 146(4), 348-361.

Posner, G. J., Strike, K. A., Hewson, P. W., & Gertzog, W. A. (1982). Accommodation of a scientifc conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change. Science Education, 66(2), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce:3730660207

Primi, C., Garuglieri, S., Gori, C., Sanson, F., Giambi, D., Fogliazza, M., & Donati, M. A. (2024). Measuring problematic smartphone use in adolescents: psychometric properties of the Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale (MPPUS-10) among Italian youth. Behaviour and Information Technology, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2023.2212816

Richter, A., Adkins, V., & Selkie, E. (2022). Youth perspectives on the recommended age of mobile phone adoption: Survey study. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 5(4), e40704. https://preprints.jmir.org/preprint/40704

Somerville, L. H., Jones, R. M., & Casey, B. J. (2010). A time of change: Behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cues. Brain and Cognition, 72, 124-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.07.003

Steinberg, L., Albert, D., Cauffman, E., Banich, M., Graham, S., & Woolard, J. (2008). Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology, 44(6), 1764-1778, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012955

Tangney, J.P., Baumeister, R.F., Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324. https://doi.org/10. 1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x

World Health Organization (2024). Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC). Retrieved at: https://hbsc.org/publications/reports/a-focus-on-adolescent-social-contexts-in-europe-central-asia-and-canada-volume-7/