European Court of Human Rights ruling on the return of “Victorious Youth” Bronze to Italy

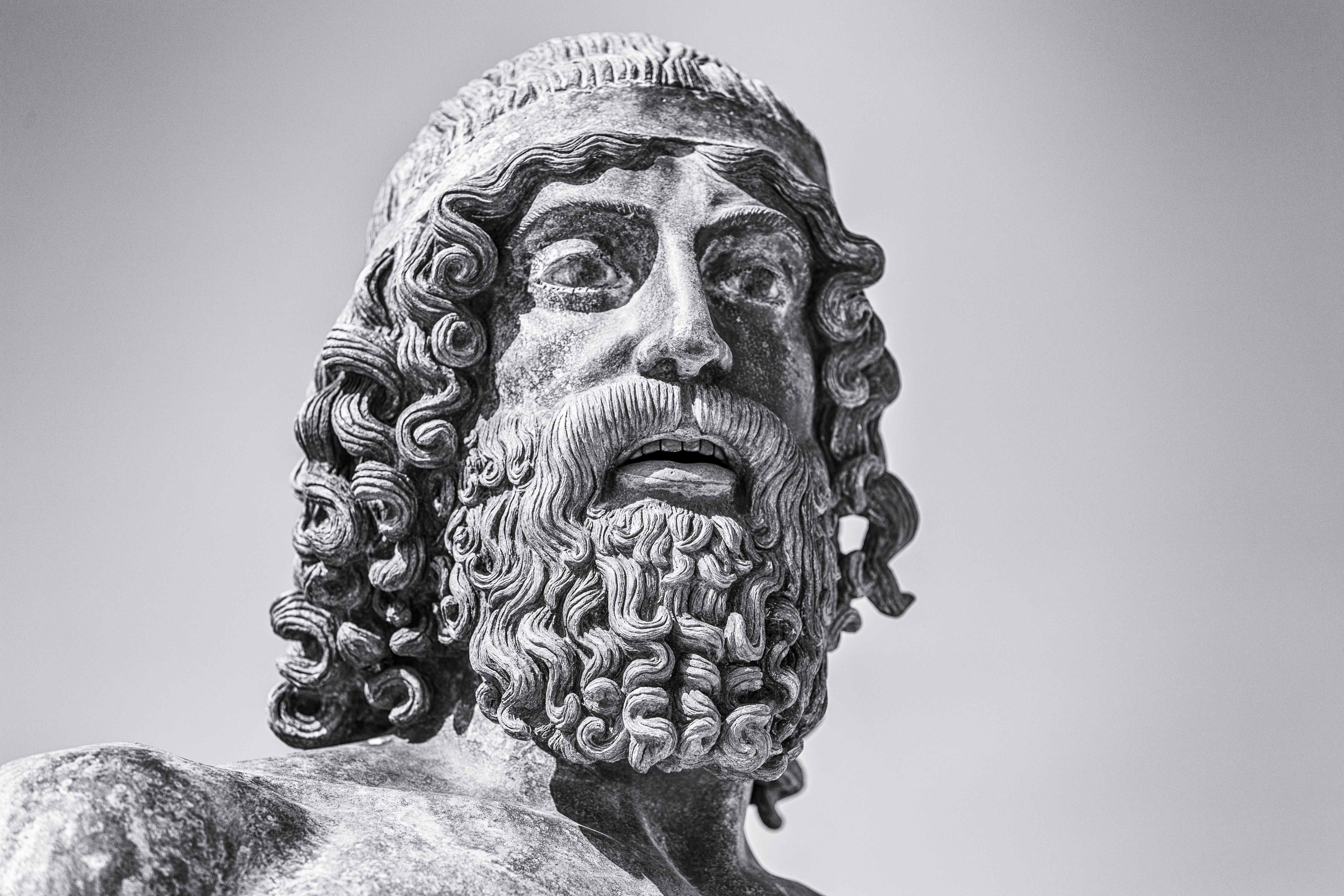

On May 2, 2024, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) rejected Getty Trust’s claim concerning the ancient Greek bronze statue known as "Victorious Youth". Since 1977, this sculpture has been on display as an integral part of the Getty Museum's collection in Los Angeles and one of its most iconic pieces.

Background of the case

The applicants alleged that by ordering the confiscation of the statue (an order was issued by the District Court of Pesaro in 2007 and reiterated in 2018; the Italian Cassation Court upheld it in 2019), Italy infringed on their right to the peaceful enjoyment of property, as guaranteed by Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

In 1964, the bronze was discovered by some Italian fishermen in the Adriatic Sea. It quickly disappeared, and Italian prosecutors started criminal investigations into the theft and illegal transfer of cultural objects. The statue reappeared in Germany in the 1970s, but the German authorities discontinued the Italian requests to seize the object and criminally charge the possessor for handling stolen goods. In 1977, the statue was eventually sold to the Getty Foundation for 3.95 million dollars. Italy has constantly operated through diplomatic channels to obtain the restitution of the artwork, maintaining it was part of the national cultural and artistic heritage. In 2006, after the suspect emerged that, during the negotiation with the German art dealer, the Getty Foundation officers expressed concerns about the potential illicit provenance of the piece, the Italian District Court of Pesaro reopened the case. The judges argued that, even though charging anyone for unlawfully exporting the statue proved impossible, the American museum was bound to return it to Italy. The American authorities have since failed to enforce the Italian court’s order despite the judicial cooperation agreements in force between the two countries, and negotiations are still going on to obtain the restitution of the statue to Italy.

Before the ECtHR, the Getty Trust highlighted that the statue was discovered in international waters, made by a Greek author, and acquired legally from a German art dealer. Therefore, according to the Getty Museum, no unlawful conduct can be attributed to it, and by issuing the confiscation order, Italy was unlawfully interfering in its property rights over the object.

Legal argumentation

The ECtHR found that Italy's judicial and diplomatic efforts to protect its cultural heritage against illegal exploitation and recovery attempts are legitimate and do not violate the Getty Foundation’s right under Art. 1, Protocol I to the ECHR. The ruling is based, besides the ECHR, on several international and European instruments, including the 1970 UNESCO Convention on Preventing the Illegal Transfer of Cultural Property, the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Cultural Objects, the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage, the EU Directive 2014/60/EU on cultural objects unlawfully removed from Europe, and Regulation 116/2009/EC on the export of cultural goods.

The ECtHR found that the Getty Foundation, although not involved in the illicit exportation of the statue, cannot claim that the recovery measures subsequently sought by Italy were unpredictable. In particular, according to the Italian law in force since the 1970s, an order of confiscation aimed at the recovery of an object in the public interest can be applied to third parties owning the relevant item in the absence of the recipient’s participation in the criminal facts and is not to be necessarily considered a punitive measure. The fact that the confiscation was ordered many years after the disputed acquisition is irrelevant, as the ECtHR recalls that in the field of cultural heritage, “States enjoy a wide margin of appreciation, not least because the measure at issue pursues the aim of recovering a unique and irreplaceable object.” The confiscation was, therefore, lawful and was also legitimate, because it was ordered in pursuance of public interest, as the affirmation that the bronze was part of the Italian cultural heritage was not arbitrary or unreasonable. Finally, the measure was proportionate, considering that, as the ECtHR put it, “[the Getty] Trust’s representatives when purchasing the Statue were, at the very least, negligent, if not in bad faith” (although some negligence was also imputable to the Italian authorities).

When Italy first tried to claim the bronze, the task proved complicated due to cultural property law limitations. The 1930s legal framework on the protection of cultural heritage in Italy applied only to the objects that were found on Italian territory, leading to confusion in the case of an object found in international waters. After Italian legislation changed in the 1970s, Italy expanded its authority over cultural property, allowing the claim of any cultural artefacts in possession of third parties. The moment Getty acquired the statue, the Italian jurisprudence was not unanimous about the interpretation of the Italian law, and the museum attempted to use this in its defence. However, the ECtHR ruled that the Getty Foundation's argument, based on outdated legal opinions, was insufficient.

Finally, the ECtHR stated that the acquisition of an ancient statue of allegedly unknown provenance by the Getty Museum undermined the spirit of the conventions that protect cultural heritage and cannot be protected under the right to peaceful enjoyment of property. This conclusion is supported by ECtHR’s notice that there is a “strong consensus in international and European law with regard to the need to protect cultural objects from unlawful exportation and to return them to their country of origin.” This ECtHR decision became final in August 2024.

Broader Context

This decision from the ECtHR has relaunched the debate about the restitution of cultural properties to the countries from where they were unlawfully taken. For example, in November 2024, the French Government decided to handover Ethiopian cultural artefacts to the National Museum in Addis Ababa through diplomatic channels. The artefacts, including two prehistoric stone axes bifaces and a stone cutter, were excavated from a site near the Ethiopian capital under a French-Ethiopian bilateral treaty and had been in Paris since the 1980s.

This is a momentous judgment in the greater context about the debate of the ownership of artefacts that are critical to a nation’s cultural heritage. One of the longest debates regarding artefact ownership in the European context has been about the Elgin/Parthenon Marbles. The marbles were a part of the Parthenon facade from which they were removed and relocated to the British Museum by the Earl of Elgin. However, the provenance and claims differ in this case, due to the fact that the removal occurred in the early 19th century, with the permission [ferman] from the then ruling Ottoman empire. The ECtHR's jurisdiction and the applicability of jurisprudence on Article 1 of Protocol 1 would arguably be more complex in this context. The British Museum holdings are protected by the British Museum Act 1963 and many attempts for negotiation and mediation through diplomatic channels including through UNESCO have not settled the dispute yet.