Gender-based violence in conflicts and securitization: problems, justice and a possible solution

Table of Contents

- The role of social norms and behaviors in gender-based violence

- The psychological reasons driving gender-based violence

- Punishment and impunity of gender-based violence

- Securitization: between advancements and new problems

- Peacekeeping and peacebuilding: friends or foes?

Gender-based violence (GBV) exists in any society, but it occurs in different forms and intensities depending on the context. Among these, it’s possible to find conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), often erroneously considered as an independent matter and as a by-product of war, leading to its normalization.

Consequently, it was not until the wars in Rwanda and Yugoslavia that the world, and in particular international organizations, acknowledged how CRSV is not simply an inevitable part of clashes. Scholars were divided between those, like Susan Brownmiller, who believed wartime rape had increased in the 20th century, and others, like Jonathan Gottschall, who viewed it as a timeless phenomenon, citing examples from the Torah and Homer’s writings, like the rape of the Sabine women.

Although CRSV has a timeless nature, it is evident that the last century witnessed an increase in its perpetration, largely due to changes in how conflicts are carried out. Similarly, the increased attention to this issue can be attributed to the 20th century technological advances in media communication and journalism, which facilitated wider reporting of sexual violence carried out by various groups during conflicts.

No sustainable solution has been found, mainly because of the multi-faceted nature of GBV, requiring case-by-case study and tailored solutions to rebuild societies in ways that prevent the recurrence of GBV. This entails a systematic change in how scholars and international organizations, as well as civil societies and activists, approach the issue.

Analyzing GBV factors alone is insufficient; the securitization theory and its application to CRSV must also be addressed. This article examines CRSV in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, and Yugoslavia, highlighting key factors, achievements, and obstacles to justice and the elimination of gender-based discrimination. While the number of reviewed cases is small, their importance allows for the identification of major elements contributing to gender-based violence in societies and wars.

The role of social norms and behaviors in gender-based violence

There are multiple theories that developed around the topic of CRSV, including the “pressure cooker” theory, the strategic rape theory and the feminist theory. The former perceives wartime rape as the result of biological imperatives. The second encompasses CRSV as a tool used by military forces to accomplish strategic objectives.

The feminist theory, however, rejects these explanations, emphasizing the diversity of experiences lived by the victims and challenges traditional gender roles and the one-dimensionality of the phenomenon, arguing that both men and women can be victims and perpetrators. This theory also introduces two critical elements: discrimination and traditional gender roles. Even if strictly intertwined, these two have many differences which are crucial in understanding the different ways in which they can lead to the perpetration of CRSV.

The Khmer Rouge's discrimination in Cambodia stemmed from class divisions present in peacetime, which the regime exacerbated to advance its ideals. The divisions present in Rwanda and Yugoslavia, on the other side, stemmed by decades of discrimination and hatred based on national and identity grounds. Within this context, not only divisions between groups became essential, but also within them: the role that women traditionally played in the different groups was used against them, as in the case of Muslim Bosnian women in Yugoslavia, who were targeted through CRSV to “undermine” the Muslim Bosnian men.

This is strictly connected to the second matter: that of traditional gender roles, which played an important role in the perpetration of CRSV in the Democratic Republic of Congo. A 2018 study by Bitenga and Moke highlighted how GBV is linked to masculinity and patriarchy:

[…]The findings suggest that sexual violence lay dormant in gender norms and in the traditional perception of masculinity in peacetime and manifested during conflict with incredible severity and brutality[…]

The psychological reasons driving gender-based violence

Social norms and discrimination, however, are not the only drivers of CRSV: psychological factors are also critical in the perpetration of all types of violence based on gender. To understand them, Eriksson Baaz and Stern have distinguished between the “sexed” and “gendered” stories.

While the first perceives GBV as the result of a biological urge and a by-product of war based on masculinity, the latter deconstructs the idea of masculinity and femininity as intrinsic, but rather perceives them as learnt through socialization processes and social groups, including the military. Any deviance from the masculine soldier image will be considered feminine and effeminate and will be fought. This understanding of gender-based violence takes into consideration how men can also be victims of other men, but also of women who, therefore, are not always victims. Lastly, it comprehends the idea that, when women are victims, they are not necessarily passive and in need of protection, but can stand for their rights.

In the light of such distinction, several psychological drivers of CRSV can be analyzed, among which, soldiers’ conditions. In the DRC, militarization was intertwined with gender discrimination present in the society before the spark of the conflict, which developed towards hypermasculinity. This, along with soldiers' dire circumstances and lack of punishment, led to widespread sexual violence against civilians.

In Rwanda and Yugoslavia, as anticipated, identity reasons, mainly connected with the concept of ethnicity, were crucial in determining the carrying out of CRSV. These divisions were the roots of a widespread carrying out of violence which also adopted a particular strategic character that transformed it into a weapon of war, where CRSV was used to fight the enemy and was perpetrated against civilians with the particular purpose of humiliation and annihilation.

Class rage, revenge and ideology were at the basis of the perpetration of conflict-related sexual violence in Cambodia. In fact, the Khmer Rouge took into consideration many aspects of the Cambodian traditions and social roles and used them as tools to perpetrate their goals and exert control over the population. One of the main outcomes has been that of forced marriage and rape within marriages. However, it did not receive attention until some victims and witnesses spoke out, and some organizations started studying the phenomenon, such as the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Cambodia and the United Nations trust fund to end violence against women.

Punishment and impunity of gender-based violence

Punishment and impunity of GBV in conflict link its perpetration to the recurrence of problematic rhetoric and factors in peacetime and peace-building time. The International Criminal Tribunals for Rwanda and Yugoslavia were crucial in opening up for the possibility for sexual violence to be considered as a crime against humanity, a war crime and even to constitute a crime of genocide. Yet, these decisions were sometimes undermined by persistent gender stereotypes, as in the case of Prosecutor v. Pauline Nyriamasuhuko, in which sexual violence committed by a woman was not considered genocide.

The DRC's justice system failed differently than the ICTY and ICTR. This justice system was plagued by many problems connected with the possibility to access courts, to know national and international law as well as to have the economic possibilities to embrace a cause. Moreover, stigma and exclusion of victims of sexual violence from their communities were a deterrent from confessing the crimes they had been subjected to. Even if the State adopted some laws and provisions trying to punish cases of sexual violence, they were not effective. Moreover, many problems of impunity related to the army itself.

In Cambodia, attempts at justice came years after the Khmer Rouge's rise to power, by which time many perpetrators were dead or elderly. Sexual violence was formally prohibited by the regime, so many victims were killed to hide the evidence. Forced marriage and rape within the military units were not legally or socially recognized as violence for a long time.

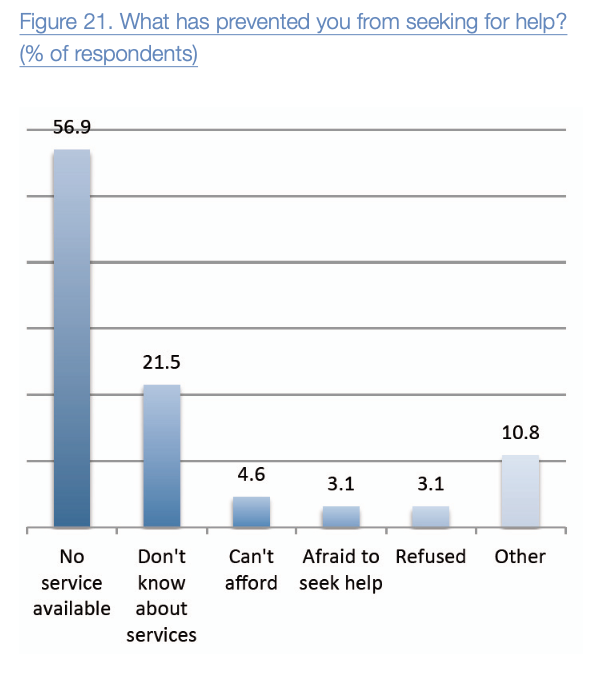

The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) were given the powers to prosecute the perpetrators of such crimes. However, many obstacles raised, such as lack of resources, but, most importantly, stigma and fear, as well as threats, were avoiding people to speak out, as shown in the graph below. Some attempts to reach justice have been made by international organizations and the civil society, for example through the project “Women and Transitional Justice in Cambodia”, which aimed at giving women a voice and a platform to speak about their suffering.

Securitization: between advancements and new problems

The acknowledgement of the new extent to which CRSV was perpetrated in the twentieth century sparked the interest of international actors, organizations and civil societies, leading to the application of the theory of securitization to CRSV. The theory of securitization is usually associated with the Copenhagen School of security studies, where it was firstly elaborated by Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver, and it was then further elaborated by other scholars.

Buzan and Wæver’s theory focused on how any non-political and political matter could become an issue of security, and how national security policies are carefully designed and created by politicians and decision-makers. In the twentieth century, the issue of conflict-related sexual violence began to be considered as a security matter and therefore the securitization theory was applied to it. The main outcome of such application was the adoption of a series of Resolutions of the Security Council of the United Nations, which, however, have been highly criticized because of the repetition of those same elements that are at the basics of gender discrimination, such as the rhetorics prescribing gender roles and the lack of acknowledgment of different forms of GBV, as clearly shown in the phrasing of Resolution 1325:

[…]Calls on all parties to armed conflict to take special measures to protect women and girls from gender-based violence, particularly rape and other forms of sexual abuse, and all other forms of violence in situations of armed conflict[…]

In the light of these problems, emerged the critic posed by Sara Meger, who criticized the inclusion of CRSV into scholarship, advocacy and policy, by affirming that this had as a result the disassociation of such acts from its context and structural roots, creating the conditions for its fetishization. This results in three stages: decontextualization or homogenization, objectification and blowback. The consequence is that conflict-related sexual violence has become a commodity which serves certain purposes for all actors. However, this reproduces pre-existing behaviors, social relations and social roles which are at the basis of the perpetration of sexual violence itself.

Peacekeeping and peacebuilding: friends or foes?

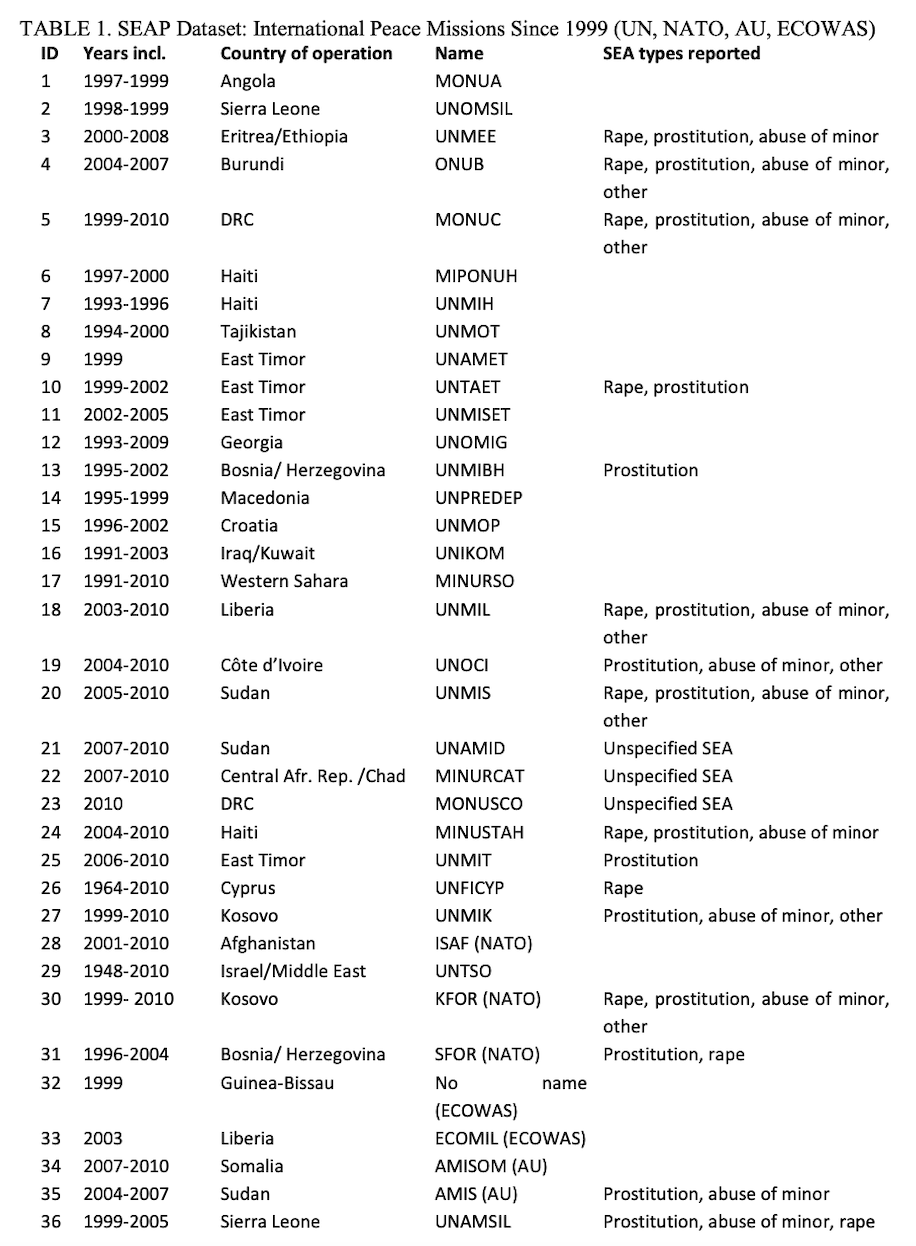

The outcome of securitization policies, however, is not only theoretical or political, but also practical, in which policies are at the basis of peace operation. The analysis of the impact that peacekeeping has on women’s safety carried out by Ragnhild Nordås and Siri Rustad on thirty-five peacekeeping missions carried out between 1999 and 2010, as well as an analysis of the reasons behind instances of sexual violence and abuse performed by peacekeepers, has emphasized a similarity between the two. In this context, sexual violence perpetrates a vicious circle of the elements that caused it, as shown in the table below.

A solution proposed by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) of the United Nations Secretariat, is that of increasing women’s roles in peace operations. This can act as a deterrent to the perpetration of sexual violence and abuse, while increasing the chances of reporting of such behaviors. However, as highlighted by Rehn and Sirleaf, the way in which such solution has been phrased highlights again those gender divisions and stereotypes which are at the basis of GBV per se. Moreover, there has not been a consistent and real practice of what has been theorized.

The reiteration of gender norms, dynamics and rhetorics that cause gender-based violence shows the necessity for the adoption of policies and peace operations which take into consideration the multi-faceted nature of this issue and give the space to victims to participate in the reconstruction, recognizing women and men with equal opportunities to be participants in these processes, but also holding them equally accountable when necessary.