Human Rights, Water and Development: what role for the United Nations?

In 2010, the United Nations recognized access to clean and safe water as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights. Water is indeed a vital resource for human survival and development, a prerequisite to sustain life and health, and indispensable to live in dignity. Yet lack of water leads to illness and death and currently, 844 million people around the world lack access to clean and safe water as the result of an already existing global water crisis, which draws from limited available freshwater resources, contamination of existing sources and current human high-water consumption patterns.

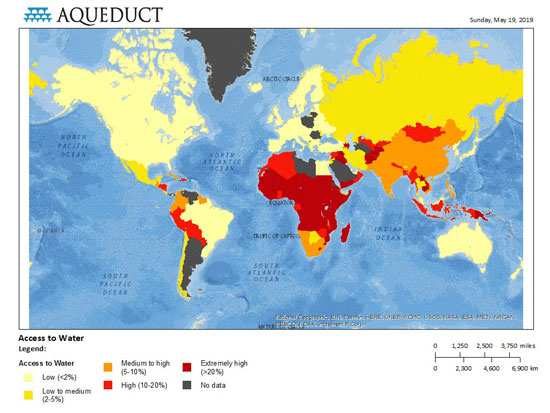

Access to water measures the percentage of population without access to improved drinking water sources (Check Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas).

The physical dimension of water scarcity is worsened by its economic and institutional features, arising from the lack of adequate infrastructures because of financial, technical or other constraints, and the failure of institutions and policies in place to ensure reliable, secure and equitable access and supply of water to users. Thus, the risk of being ‘left behind’ in terms of access to water is more likely to be faced by the most vulnerable groups around the world, according to different grounds of discrimination, including sex, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, national origin, birth, caste, language, nationality, disability, age, health status, property, tenure, residence, economic and social status and other grounds.

After a long process, the historical moment for the formal recognition of the human right to water within the international community dates back to 2010, when the United Nation’s General Assembly adopted the landmark resolution The Human Right to Water and Sanitation eventually recognizing “the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights”. The normative content of the right, as elaborated in the General Comment No. 15 of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, accessible and affordable water of an acceptable quality. Moreover, the Resolution has been strengthened, a few months later, by the Human Rights Council, which through the resolution Human rights and access to safe drinking water and sanitation affirms that “the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation is derived from the right to an adequate standard of living and inextricably related to the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, as well as the right to life and human dignity”.

Although the two resolutions are not legally binding in their nature, but rely on strong political commitment, they represent a milestone for the universal recognition of water as a human right, therefore calling on states and all relevant stakeholders to comply with their obligations to respect, protect and fulfill the right. Remarkably, the recognition of the right to water under International Human Rights Law counterbalances the neoliberal understanding of water commodification, resulting from the the 1992 Dublin Conference on Water and Environment, which acknowledges the economic value of water against wasteful and environmentally damaging uses of the resource. The economic value of water embraces the private sector as enabler of a more efficient management of natural resources through the mobilization of long-term investments, including multinational corporations’ foreign direct investments, aimed at providing clear incentives to improve the performance and sustainable use of resources. This is the powerful rationale shaping the establishment of a Global Partnership for sustainable development foreseen in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and calling for partnerships between governments, private sector and civil society in order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

Given the current scenario of the global water crisis, whereby both public and private entities concur for the ownership and management of water resources, plausible questions arise on who is responsible with respect to the realization of the right to water, prioritizing a pro-poor, non-discriminatory and safe freshwater service provision over the prominent commodification of the resource. Indeed, the normative content of the human right to water does not deny the role of private actors in its realization, on the contrary it defines obligations and commitments both for states and private actors to be respected in order to make access to water achievable. The Human Rights Council resolution recognizes that States, in accordance with their laws, regulations and public policies, may opt to involve non-State actors in the provision of safe drinking water and sanitation services and should ensure transparency, non-discrimination and accountability. Thus, the private sector can actually contribute by improving efficiency, increasing the extension of services and allocating more investments to relieve States from their deficits and failures, under the condition to include the respect and realization of the right to water in their core business operations and decision-making processes. But this does not exempt the State from its human rights obligations: it remains the primary duty-bearer and should ensure compliance of all stakeholders with core human rights obligations. Therefore, from a human rights perspective, the crucial question is not whether the private sector should be involved in the delivery of water services, but how the arrangement is structured, implemented, and monitored, in order to reconcile the idea of market principles with the human right to water.

Generally, private sector engagement in water management and supply mainly takes two forms: privatization, which has been the official mantra of many development agencies since the 1980s, and participation at the international decision-making level by the means of Transnational Water Policy Networks, such as the World Water Council, the Global Water Partnership and the World Commission on Water in the 21st century. Although the potential of this engagement is powerful, several cases of privatization, sharing the lack of political commitment by states to ensure stakeholders’ compliance with the provisions set out by the content of the human right to water, have turned inefficient and undermined the entitlements to accessibility, availability acceptability and quality of water for users.

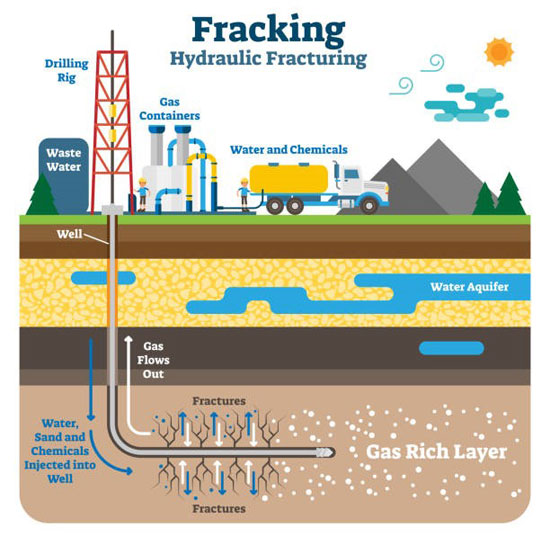

Full privatization of water management and supply systems in England (1989 Water Act) led to investments allocated in inefficient projects and infrastructures unable to solve the high rate of water leakages and reducing consumers’ availability and physical accessibility of water, while increasing tariffs against the affordability of water provisions for consumers. Moreover, privatization in England has evolved in new forms of water management and exploitation relying on the water-energy nexus. This is the case of hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as fracking: the process of injecting liquid at high pressure into less permeable subterranean rocks so as to force open existing fissures and extract shale gas, coal-bed methane and tight oil.

Besides the debatable benefit on energy production, fracking is particularly dangerous in terms of water quantity and qualities, which are both environmental and human rights concerns. Shale gas production is a highly water intensive process: a single well requires around 5 million gallons of water - where sand and chemicals are added- and an average well-pad cluster up to 60 million gallons to drill and fracturing. Regularly, the large quantity of water used by the fracking industry is freshwater held below the ground, a factor which easily stresses water scarcity. Another main concern is related to the quality of water. Groundwater sources are indeed likely to be contaminated by the extracted gas or by wells’ failures, making water no reusable.

Similarly, the case of privatization beginning in 1989 in Buenos Aires through the contract of concessions of drinking water services and sewerage to the consortium Aguas Argentinas did not lead to successful results for water consumers. Although the consortium and the government pointed out a clear reduction of tariffs during the years of the concession, this was the result of prior purposely raised tariffs for water services provision by more than 62% through a new tax, enhancing the idea of the benefits possible through privatization. Moreover, investments for services expansion and improvements were not allocated. Thus, the negative effects on the affordability, availability and accessibility of water services for consumers were tangible. The experience of profit-driven privatization taking place in Buenos Aires at the expenses of poor households, workers and the quality of water, led the municipality to react to the failure of private providers taking back public control over water and sanitation management. This emerging countermovement phenomena to the paradigm of privatization, occurring since the 2000s, is labelled remunicipalisation: the return of previously privatised water supply and sanitation services to public service delivery (Check Water Remunicipalisation Tracker).

The briefly introduced cases of privatization of water management services are a clear manifestation of how the power to impact upon human rights draws not only from states but also from powerful non-state actors, namely business and corporate enterprises, which therefore also play a crucial role in the realization of human rights. They are called to avoid undermining human rights by the means of their own operations and to address negative human rights impacts when they occur in direct or indirect relation to their activities. Accordingly, the United Nations and other intergovernmental bodies have engaged towards the realization of a legal framework aimed at regulating the behaviour of corporate business with respect to human rights obligations, attaining a body of business responsibilities relying on the widely accepted standards of corporate social responsibility. It assumes that along with the main scope of pursuit of profits and shareholders value, corporations have obligations towards human rights, labour standards and environmental conservation. Undoubtedly, corporate social responsibility is coherent with human rights standards. However, it mainly consists of corporate actors’ voluntary commitments based on reputational risks, which relying on principle-based structures, such as the UN Guiding Principles, the CEO Water Mandate and the UN Global Compact, misses to create a legally binding system regulating business operations with respect of human rights and environmental standards.

In 2014, the effort for the establishment of a normative international framework legally binding on transnational business conduct received a new lease of life with the Human Rights Council resolution setting an open-ended intergovernmental working group on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights (IGWG), whose mandate shall be “to elaborate an international legally binding instrument to regulate, in international human rights law, the activities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises”. The result of the first three sessions held by the IGWG group issued the Zero Draft Legally Binding Instrument to regulate, in international human rights law, the activities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises (Zero Draft), as well as a Zero Draft Optional Protocol to be annexed to the Zero Draft Legally Binding Instrument. The Zero Draft aims at strengthening states’ human rights obligations and recognizing legal liability of corporate actors under international law. State Parties shall indeed ensure through their domestic law that “natural and legal persons may be held criminally, civil or administratively liable for violations of human rights undertaken in the context of business activities of transnational character”.

The Zero Draft is a key milestone in the process to create a legally binding treaty on business and human rights. Its content has first been discussed during the fourth IGWG session held in 2018. Negotiations to actualize the final legal instrument, ratified by nations and available for affected communities and individuals to claim their rights and remedies for corporate abuses before national courts, are still lengthy. However, the initiative calling on states to recognize the legal accountability of corporations and other business enterprises for the human rights violations resulting from their operations, would set a significant new framework for the respect, protection and fulfilment of human rights. Notably, in the case of the universal right to access safe and clean drinking water, in the midst of industrial private operations requiring freshwater for profits, a binding regulatory framework is crucial.

To conclude, the initiative of the Zero Draft within the United Nations is noteworthy. It is now time for States to move beyond the acceptance of dissatisfactory voluntary corporate social and environmental commitments and to comply with their international human rights obligations by holding business actors accountable for their human rights abuses. The fifth session of the IGWG will be held in October 2019 and with respect to the cross-cutting and crucial importance of the human right to water for human survival and the enjoyment of all other rights, and given the urgent nature of the freshwater ecological, economic and institutional crisis facing the world today, a legally binding instrument could hopefully set a legal framework where corporate operations related to freshwater are compliant with the right of all to equally access freshwater of sufficient quantity and adequate quality.