"Leaving no one behind": An empty promise for climate-induced internally displaced populations? - Local integration challenges and solutions in Bangladesh

Table of Contents

- Goal

- Background

- Bangladesh: A Country in the Frontline of Climate Change

- Local Integration Provisions according to International and National Policy Frameworks

- The IASC Framework on Durable Solutions for Internally Displaced Persons (2010)

- Bangladesh’s National Strategy on Internal Displacement Management (2021)

- Challanges to "Successful" Local Integration of Climate-IDPs in Khulna, Bangladesh

- A Glimmer of Hope: "Not all who wander are lost" (J.R.R Tolkien)

Goal

The overall study focuses on the complexities regarding the urban local integration of climate-induced IDPs in Bangladesh by illuminating the role of public institutions and policies in ensuring durable solutions through the lens of multi-level governance systems. By juxtaposing 'de jure' rights provisions and 'de facto' lived experiences of city representatives and climate-IDPs themselves, the thesis contributes to the broader discourse on the interconnected challenges and opportunities of climate-induced internal displacement to urban areas.

Background

Human migration has historically served as an adaptation strategy to find more desirable livelihood opportunities in new destinations.

However, in recent decades, increased climate variability and extreme weather events due to global warming have led to rising numbers of displaced individuals, both internally and across borders, raising concerns about their economic, political, environmental, social, and security impacts on societies.

Climate change disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, often pushing them to migrate due to exacerbated hardships. Therefore, climate change induced disasters often end up acting as a ‘threat multiplier’ and for many become the tipping point that creates enough incentive to escape the unbearable precariousness back home.

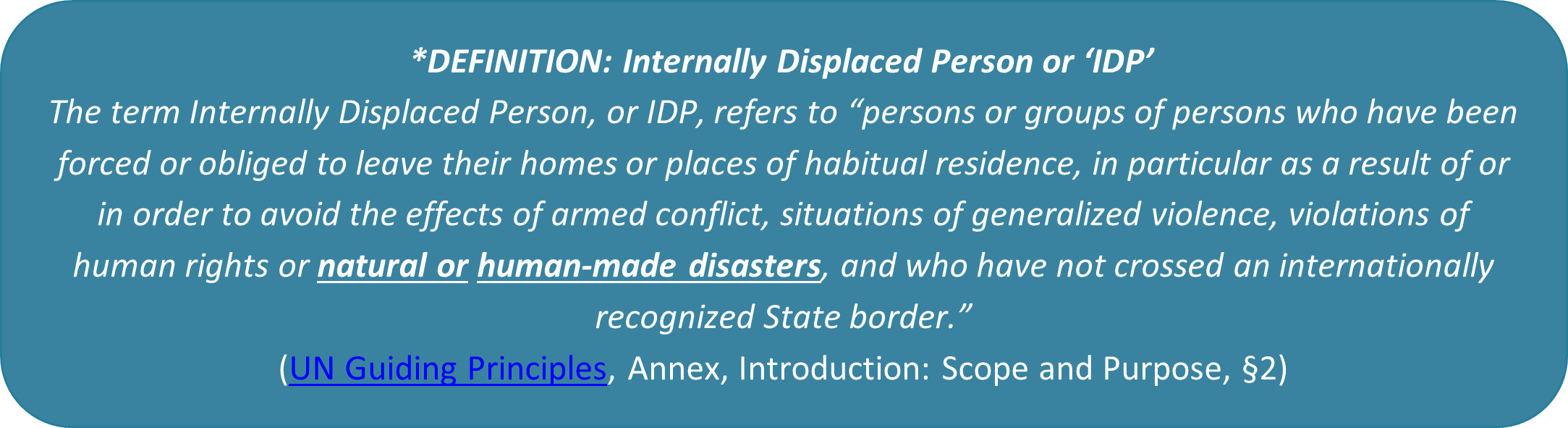

In search for better living conditions, especially climate-induced Internally Displaced Persons* (so-called ‘IDPs’) face important legal protection gaps due to the absence of an internationally formalized ‘IDP status’. However, without the legal recognition of the distinct challenges climate-IDPs face, most of those affected have little possibility to claim public support and are often left with no alternative but to settle in urban slums where they face increasing impoverishment and precarity.

As climate-induced displacement is likely to become permanent due to unrecoverable loss of territory and livelihoods back home, policymakers are recognizing the need for long-term solutions, such as local integration, in destination areas. This approach, supported by the 2018 OECD report on Local Integration of Migrants and Refugees, emphasizes the importance of the local level in migrant integration management, as local integration varies based on the specific characteristics of cities and regions.

Bangladesh: A Country in the Frontline of Climate Change

Bangladesh, highly exposed to climate change impacts like river flooding, erosion, rising sea levels, salinity, and cyclones, ranks as the 7th most disaster-affected country globally according to the 2021 Global Climate Risk Index. In fact, between 1980 and 2008, it faced 219 disasters, including the significant cyclones Sidr (2007) and Aila (2009). The country is also South Asia's most affected country for climate migration, with annual internal displacements nearing 915,083 people. By 2050, climate-induced internal displacements are projected to exceed other internal migrations, potentially affecting 13.3 million people (7.53% of the population), according to the World Bank’s 2018 Groundswell Report.

Amidst high population density and rapid urbanization, Bangladesh has become a key figure in international climate diplomacy, advocating for emissions reduction and compensation for developing nations. It is also noted for its comprehensive national strategy on managing climate-related internal displacement, making it a relevant case study in addressing climate-induced displacement challenges at policy level.

Local Integration Provisions according to International and National Policy Frameworks

The IASC Framework on Durable Solutions for Internally Displaced Persons (2010)

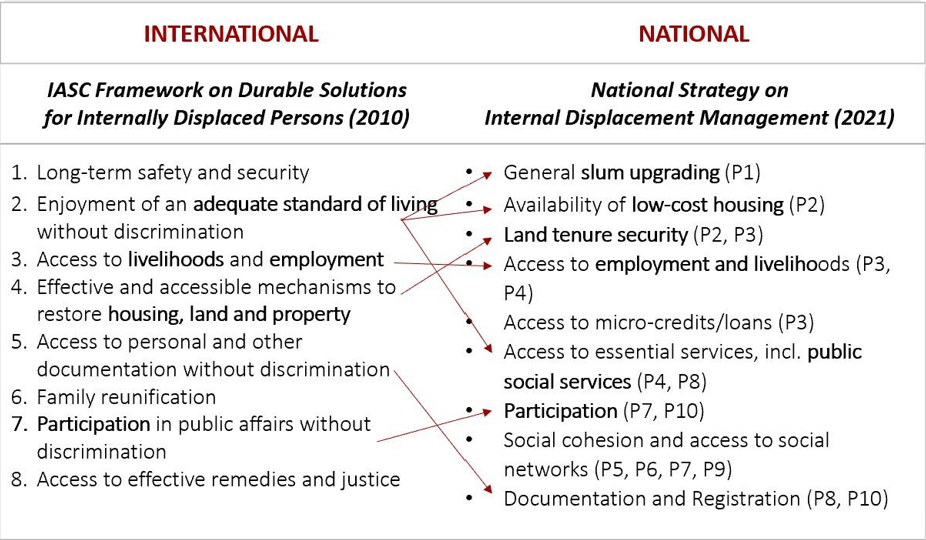

In 2010, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) published a Framework on Durable Solutions for Internally Displaced Persons (or ‘IASC Framework’) which is based on the historical UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement (1998) - the most widely recognized document for internal displacement-related policy making. The IASC Framework mainstreams three durable solutions:

- Sustainable reintegration at the place of origin (“voluntary return”),

- Sustainable local integration in areas where internally displaced persons take refuge (“local integration”), and

- Sustainable integration in another part of the country (“resettlement”).

To tackle the second of these durable solutions, the international framework proposes eight key priority areas (see Figure 2), whereby ‘local integration’, according to the IASC Framework, is ultimately achieved when “internally displaced persons no longer have any specific assistance and protection needs that are linked to their displacement and such persons can enjoy their human rights without discrimination resulting from their displacement” (IASC Framework, 2010, 5).

Bangladesh’s National Strategy on Internal Displacement Management (2021)

Bangladesh's 2021 National Strategy on Internal Displacement Management (or ‘National Strategy’) is a pioneering document which recognizes the intertwinement between climate change, internal displacement, urbanization, and local integration. It addresses five of the eight internationally established priority areas identified in the IASC Framework (see Figure 2). While overlooking three significant international conditions for local integration—long-term safety, family reunification, and access to justice—it goes beyond international standards in other areas, notably in facilitating financial linkages and social networks. A notable aspect of the strategy is also its distinct definition of a 'Disaster and Climate-induced Internally Displaced Person', especially significant in the absence of an internationally agreed upon definition for climate- related displaced persons. This definition encompasses individuals, groups, or communities compelled to leave or be evacuated from their homes temporarily or permanently due to sudden or slow-onset climatic events and processes, without crossing international borders.

However, despite their valuable contributions in terms of policy precedents, none of the two outlined policy frameworks are legally binding, which may obstruct effective localization at subnational level.

Challenges to "Successful" Local Integration of Climate-IDPs in Khulna, Bangladesh

modified from Lexas Länderservice

While internal displacement and disaster management policy is set at the national level and are informed by international standards and state obligations, migrant integration policies are generally implemented at the subnational level. However, this is also the level which is most detached not only from higher policy-making processes, but also from necessary financial resources and execution authority. In Bangladesh, institutional weakness compounded by mismatches across different levels of governance, as well as overlapping jurisdictions of different local actors, tend to hinder effective decentralized governance, which have serious implications especially for disadvantaged populations.

The human face of inadequate policy localization in the context of climate change adaptation

The consequences of such structural obstacles are indeed discouraging: Climate-IDPs report significant shortcomings in living standards, access to adequate employment and livelihoods, land tenure security and safety, as well as access to institutionalized support systems.

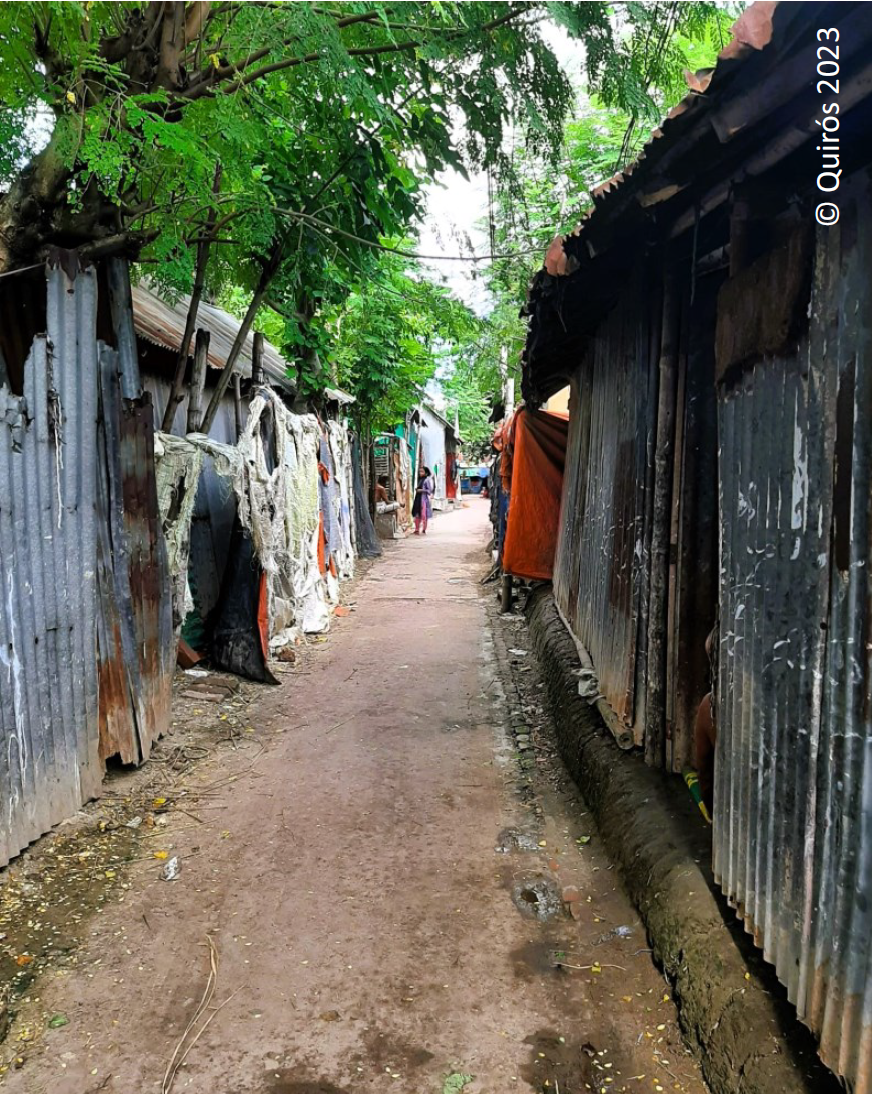

In fact, according to the survey conducted in two informal settlements (so-called ‘slums’) in Khulna city, namely Greenland and Rayer Mahal, 70% of the 30 interviewed climate migrants live in tin shed houses that fail to protect against any weather conditions, exposing them to extreme heat, waterlogging, flooding, and muddy grounds in their own houses. Furthermore, drinking water is sometimes reported by climate migrants to be saline posing serious health risks, while showers and toilets must be publicly shared among some 9 to 15 families. With a notable 40% of the respondents being unemployed and the remaining 60% carrying out informal activities, financial instability not only poses additional challenges to making ends meet for families, but also further deprives individuals of the possibility to be effectively integrated into society.

On top of these socioeconomic shortcomings, the lack of access to land tenure and property rights in the informal settlements, leaves climate migrants exposed to a series of human rights violations outlined in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including the right to an own property, privacy, a life in safety and free from (psychological) torture, as well as arguably to live free from arbitrary exile. According to the local government’s chief town planner, 90% of slums have developed illegally on government land, which often becomes the justification for slum evictions. As the government insists on being able to access its lands at any time, permanent structures are prohibited and therefore slum upgrading possibilities – as intended by Bangladesh’s National Strategy (see Figure 2) – become extremely limited. Eviction threats to the settlement residents are common and cause pervasive fears among the residing climate migrants who are forced to remain in a continuous limbo.

Furthermore, while there are public social services intended for the broader disadvantaged population, they don't specifically cater to the needs of climate migrants. Similarly, the reach of these services is so limited that most climate migrants, even if eligible, don't benefit from them. As a result, the primary sources of support for these individuals are often not city authorities but their personal social networks and non-governmental organizations, which step in to offer essential infrastructure and social services in the slums.

The principle of ‘Leaving no one behind’ is a central commitment of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (‘SDGs’), emphasizing the progress for all, particularly the most vulnerable. However, in light of the above-outlined shortcomings, one may be led to question this principle as climate-induced internally displaced populations in Bangladesh continue facing chronic marginalization and lack of adequate support and targeted integration policies at local level.

A Glimmer of Hope: "Not all who wander are lost" (J.R.R Tolkien)

Although the ongoing marginalization of climate-induced internally displaced populations is admittedly little encouraging, there is reason to hold out hope and commitment.

For one thing, integration is happening with or without the support of public institutions. In fact, displaced communities are forging their own spaces for integration and access to communities and labor markets through alternative means. These grassroot strategies for local integration, such as resorting to private social networks and informal entrepreneurship activities, have been a significant source of resilience for the affected individuals and have partly compensated for the lack of proactive support from public institutions.

Additionally, development actors and local associations are actively exploring new ideas and initiatives to facilitate bottom-up solutions. A notable example is the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) pilot initiative in Khulna, which has established a registration booth for climate migrants in collaboration with Khulna City Corporation (KCC) local government. This registration booth is the first in Bangladesh and aims at identifying climate migrants, providing them with relevant information about general public social services offered by the various government departments, and assisting them in application procedures.

Considering these elements, a dual approach to the local integration of climate-induced IDPs could offer a pathway to approximating the theoretically existent policy provisions and the present de facto integration challenges:

On the one hand, a top-down approach is needed to technically and financially empower local public institutions. This would include the developing and enforcing of city action plans for the socioeconomic integration of affected populations, allocating targeted and sufficient budgets from the central government to local governments, as well as building staff capacities to provide the relevant services. On the other hand, the institutionalization of proven grassroot solutions, such as the above-mentioned registration booth, would acknowledge the diverse challenges faced by climate-displaced populations and bring a modern, context-specific, and evolving approach to their local integration.

With a serious commitment across diverse actors and levels of governance, one day we may be able to transform the famous words spelled out by author Tolkien “Not all who wander are lost” and declare once and for all that “All who are lost wandering are found”.