Performing rights. The social and political potential of dance in the HR discourse

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Interdisciplinary theoretical framework: Sic-sensuous and self-transcendence

- Case studies:

Cueca: Chile’s national dance through different social and political contexts

German modern dance and Nazism: the illusion of freedom - Human Rights choreographies

- Unveiling dance’s potential for the HR discourse

- A human right to dance and to enjoy dance

Introduction

The language of dance embodies its aesthetic expressive character, social functions, and ability to express the human experience. As Klein underlines, “Dance is a world in itself.” This sentence raises an intriguing question: as a world, how does dance relate to human rights?

Eyerman suggests arts can be one of the key elements in defining a social movement, shaping emotions and ideas. Simultaneously, dance can represent what Julia Eckert defines as practice movements - unorganized and unrepresented collective actions that reflect invisible aspirations and wants, aiming not to govern, but to improve life’s conditions.

While verbal communication takes the lead when defending human rights, a performing art such as dance might foster inclusiveness.

Interdisciplinary theoretical framework: Sic-sensuous and self-transcendence

To navigate the intersection of dance and human rights, I use two key concepts: "sic-sensuous" moments and "self-transcendence."

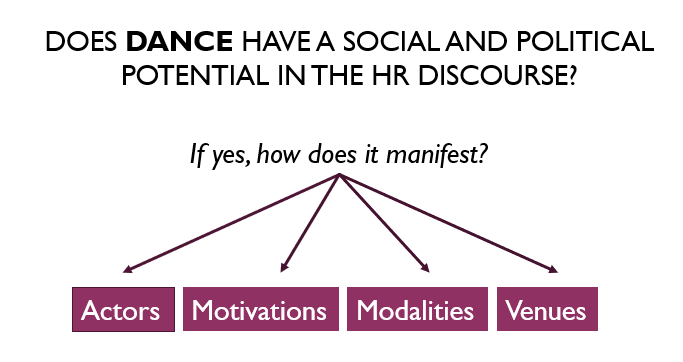

Figure 1 Social and political potential of dance

Sic-sensuous moments (Dana Mills) consist in the transfer of meaning through the processes of intervention occurring between sensed and sensing bodies, dancers and spectators. Dance generates then embodied spaces that promote equality between individuals. I propose that sic-sensuous moments do not always translate into positive outcomes for human rights: individuals might reach equality in communication through dance, but simultaneously view themselves as superior to other human beings.

Self-transcendence (Hans Joas) refers to experiences in which an individual is taken beyond the limits of his ego, embodying his self-realization, along with recognition of limitations. Such experiences aren’t necessarily (morally) good, sometimes leaving us vulnerable and shattered and they possibly establish motivation, generating the moment when commitments to value take root in the human personality. Dance, as an experience of self-transcendence, would involve a “fusion” of elements: nature (the bodies involved), music, and space.

Figure 2 Theoretical framework

When merging the two theories, sic-sensuous moments emerge as catalysts of experiences of self-transcendence through dance. The positive or negative potential of these experiences appears dynamic throughout the selected case studies, depending on the actors, modalities, and motivations involved.

Case studies

Cueca: Chile’s national dance through different social and political contexts

The traditional cueca, known in Chile since 1824, is a figurative depiction of the mating ritual between a rooster and a hen. Cueca sola, in contrast, emerged as a protest dance against the “disappearances” during the Pinochet dictatorship, portraying the absence of a partner, friend, or brother.

The elements of the traditional cueca were seized by the regime to symbolize a unified Chilean cultural identity. Cueca became the National Dance of Chile through Decree Law No.23 of the 18th of September 1979, defining it as “…the most genuine expression of the national soul”, pointing to a set of values and cultural elements associated with Chilean identity. Modalities of instrumentalization included the teaching, divulgation, endorsement of cueca and the organization of an annual contest for school students.

Figure 3 Traditional Cueca (Creative Commons)

One the other hand, the associations Agrupación de Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos and Colectivo Cueca Sola have pursued a positive instrumentalization of cueca.

AFDD, predominantly made of women blood-related to “detenidos desaparecidos”, merges the public and the private spheres. Relevant performances include their first performance, on the 8th of March 1978 in Teatro Caupolicán, which acknowledged the link between domestic violence and state violence; and the participation in the “NO” campaign of 1988 with a television slot, attaching a visual image to a collective suffering and contributing to the defeat of Pinochet. Nowadays, AFDD remains active in contemporary events: on the 11th of September of 2023 the association performed in the celebrations of the 50th anniversary of the military coup.

Figure 4 Performance of Colectivo Cueca Sola, September 2017 (Dalia Chiu, Creative Commons)

Similarly, the contemporary Colectivo Cueca Sola uses cueca sola as a main tool to work with memories and human rights. With a very diversified membership, including women and sexual dissidents, the Collective bases their actions on open calls through social networks. Their first performance, very similarly to AFDD, took place on the International Women’s Day, in 2016, highlighting the need for the de-privatization of memories, showing the connection between gender violence and State terrorism. Interventions in the Chilean Social Outburst of 2019, in heterogenous venues such as the Gabriela Mistral Cultural Center (GAM) and outside the Baquedano subway station, as well as the performances during the 11th of September commemorations next to the monument of Salvador Allende in Plaza de la Constitución and La Moneda, and an audiovisual map of people performing cuca sola during Covid-19 pandemic highlight their mission.

Accordingly, both the negative and positive instrumentalization of cueca generate moments in which values take root in the human personality, prompting cultural indoctrination or reflection on human rights violations.

German modern dance and Nazism: the illusion of freedom

Scholar Marion Kant argued arts played a key role in the accessibility of völkisch ideologies to a wider public. Modern dance artists like Rudolf Laban and Mary Wigman collaborated with the Third Reich Ministry of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment (Kant, 2016), even if eventually they were also seen as “degenerate”. In the first years of the Third Reich, modern dance (Ausdrucktanz) was perceived by the regime as representing the dancing German individual, through which the German soul could be pulled out of the instructed body. Through the directive No.26 of July 1934, dancers needed state certification to be able to exercise their profession. Eligibility for state certification belonged only to those of Aryan origin.

When framed through the theoretical framework, this idea has a very strong symbolism: dance as a medium through which Nazi values could be grounded in the individuals.

Rudolf Laban advocated for an atmosphere of military discipline combined with the occult and antirationality in his classrooms, where dancers would renounce to individuality and rationality and assign responsibility to a higher authority. Laban’s Festkultur, officially “community dance” (Gemeinschaftstanz) during Nazism, sought to reawaken the lost emblematic character of festivals and prompt people of the cities to merge with a reality outside their ordinary daily experiences. Although, according to Laban, this experience was ideology-free, it should be part of a “new folk-dance movement of the white race”.

Figure 5 Mary Wigman's "Hexentanz" (Creative Commons)

Similarly, Mary Wigman engaged with state-sponsored initiatives such as the program of Tanzgesänge (Dance Songs) staged under Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy); and the famous Olympic Youth of 1936, the opening night show for the Berlin Olympic Games. Wigman sought to create a dance language reflecting a universal connection to humankind, her diaries talking of feelings of self-abandonment to serve a cause not yet created, eliminating individual expression in favour of the collective. “Hexentanz”, one of her most notable works, was sponsored by the regime in July of 1934. Despite its feminist undercurrents, themes of witchcraft and witch persecutions have resonated with the Nazi administration.

Human Rights choreographies

Human rights choreographies are a key concept worth mentioning. They describe performances that focus on human rights themes, regardless of whether they are a part of social and political movements or not.

Throughout the world many examples of this concept emerge. In Sweden, the past work of Cullberg Ballet sheds light on how ballets can be an instrument of protest. In Rapport (1970), Birgit Cullberg was inspired by the Chilean military dictatorship, contrasting two main groups, the Poor and the Rich; and Mats Ek’s “Soweto” was inspired by the Apartheid in South Africa, featuring Mother Earth as mediator. In Mexico, Barro Rojo Arte Escénico (BRAE), used dance to address human rights violations in Latin America, with performances ranging from themes such as the fight for liberty of the population of El Salvador, the phenomenon of political prisoners, and the universal feelings accompanying those exiled due to conflicts. A more contemporary example includes Botis Seva’s “BLKDOG” (2021), a piece merging hip hop and contemporary dance, portraying the feelings that accompany depression and how society is affected by mental health issues. The right to health emerges then as one of the main human rights topics in “BLKDOG”, revealing the work as an expression of universal messages.

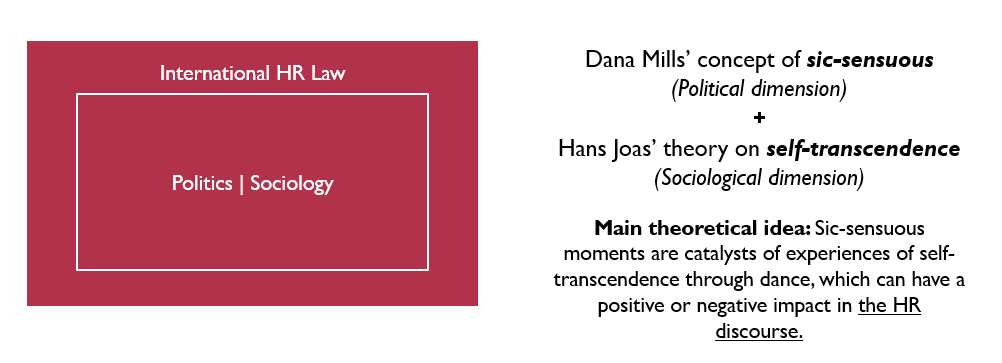

Unveiling dance’s potential for the HR discourse

Dance’s potential emerges then across an interconnected axis.

Figure 6 The social and political potential of dance explained

Identifying its potential requires considering factors such as intent; venues of socialization; social/political context; main actors involved (active participants, financers and supporters); and the message of the performance. As observed, the social and political potential of dance differs across the case studies.

Dance as a way to transmit and re-elaborate memories is evident from the performances of cueca sola in the streets of Santiago to the way Botis Seva and Far From the Norm reflect on childhood memories and mental health. While quantifying or qualifying the experiences is challenging, if we agree with Rancière, and the spectator is not passive simply because he is observing, reflecting on individual and collective memories through dance appears a very plausible scenario.

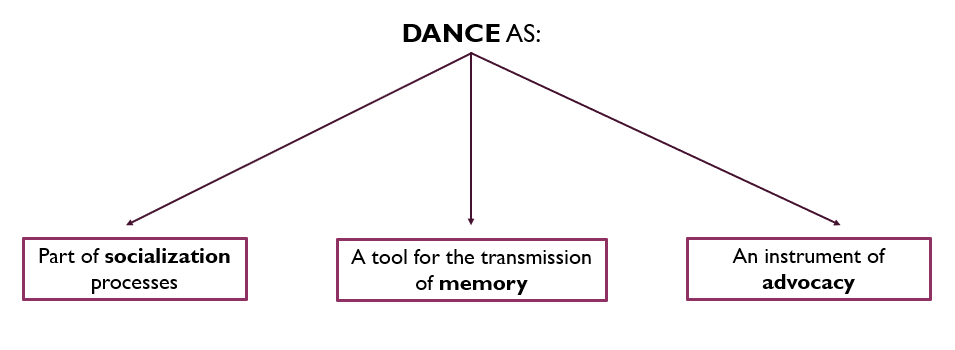

Dance emerges equally as a tool for advocacy, whether the motivation is contrary or in favour of the human rights discourse. In fact, efficient communication remains crucial, as underlined in FRA’s 2018 report “10 keys to effectively communicate human rights”.

Figure 7 Reading the language of dance through FRA's 2018 report reveals its potential as a human rights advocacy tool

Among the ten keys, telling a human story emerges as a common element throughout the case studies. We might identify our humanity in dance because we share kinaesthetic empathy with the dancer, and in this sense, we are able to read a human story shedding light both on our potential and limitations as human beings. Identifying themes of general interest might more easily trigger people’s core values, which is directly related to authenticity: Which dance will resonate more with my audience? Which theme is more relevant for them right now?

Prominent contemporary campaigns, such as 2024 UNESCO’s “#DanceForEducation”, and the 2020 “When The World Pauses, Music And Dance Continue”, further illustrate dance’s advocacy potential.

Figure 8 2024 UNESCO's #DanceForEducation campaign

A human right to dance and to enjoy dance

This exploration leads us to consider whether a human right to dance exists.

Protecting the individuals involved in dance requires several human rights: cultural rights, freedom of opinion and expression, freedom of peaceful assembly, as well as the right to strike, the right to education and the rights of human rights defenders. The 2001 UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity sustains that culture is the “common heritage of humanity” and the 2007 Fribourg Declaration on Cultural Rights reinforces the idea of dance as a cultural right, while UNESCO’s 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage includes “performing arts” as expression of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Politically, a human right to dance could be articulated through Mills’ theory that dance is able to generate an embodied space of communication between the participants, establishing equality. Inclusivity would be key: the concept of “dancer” would encompass both professionals and amateur participants. From a sociological standpoint, dance is an example of socialization and fosters experiences of self-transcendence. While a comprehensive sociology of dance is yet to develop, it could explore how dance is able to express values, cultural and social messages, and identities; as well as the effect society might have on the body.

The intersection of international HR law, Mills’ sic-sensuous and Hans Joas’ self-transcendence reveals dance’s potential for the HR discourse. In shared embodied spaces, individuals go beyond their own egos, realizing their potential and vulnerabilities, ultimately transforming their commitment to values.

In fact, the acknowledgment of dance in the human rights discourse is not novel, it builds on a relevant foundation. Efforts by UNESCO and the International Dance Council (CID), confirm dance’s universal character. Accordingly, recognizing a human right to dance would possibly elevate cultural themes in human rights discussions, promote non-traditional theoretical approaches, and encourage funding for artistic educational and advocacy programs focusing on human rights.

Ultimately, readers are left with a compelling question: is there a human right to dance?