Policy Solutions to Realise the Right to Food of Children in Colombia: An Integrative Approach

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The human right to food

- Food, nutrition, and their human rights implications

- Public policy obstacles to the human right to food

- Outsourcing the state’s obligations towards the right to food

- Centralisation dynamics

- Impaired public participation

- A reductionist approach to food and nutrition policy

- Conclusions

Introduction

Observing that the academic literature that specifically analyses the policy barriers to the right to food is scarce, this thesis intends to contribute new insights to the research gap. By means of a literature review, a review of the legal framework on the right to food, a country case study, and a thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews with eighteen experts, the study examines the public policy obstacles to overcoming early malnutrition and the features that such policies might need to be effective. Colombia was chosen as a case study considering that it is a state in deep food crisis and above the average rates in Latin America. Children were the target population because, although they enjoy special protection under the Colombian legal and policy framework, child hunger remains startling. The interviewees pertained to governmental institutions, international cooperation agencies, civil society organisations, and academia. The sample was gathered through a mix of convenience and snowball sampling. The final aim of this work is to build a set of human rights-based policy recommendations with solutions to the obstacles found suitable for Colombia and countries with shared socioeconomic and policy features.

The human right to food

In 1948, the human right to adequate food was initially recognised by article 25(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) as a component of an adequate standard of living. Ever since, attention to the development of law and policy frameworks to protect and enforce the right to food rose significantly at the national, regional, and international levels. In 1966, article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) singled out the right to food and endowed it with binding status. During the ICESCR drafting in the 1960s, several delegations stressed that the right to food was the most crucial in the treaty, as “no human right is worth anything to a starving man”. The three decades after the ICESR adoption saw a progressive increase of movements advocating for the right to food and demanding greater clarity on its content. In response to the reiterative requests, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) enacted General Comment number 12 on the right to adequate food (GC 12), which outlined the core content of the right to food and the measures to guarantee it.

According to GC 12, the right to food is the condition by which every person, alone or in community, has permanent physical and economic access to adequate food or means for its procurement. CG 12 points at three elements of the right: availability, accessibility, and adequacy. Availability implies that nutritious, safe food is at disposal through sustainable food production, fishing, hunting, gathering, or markets. Accessibility means guaranteed economic and physical access to food. Economic accessibility denotes that adequate food for a healthy diet must be affordable to everyone without compromising other basic needs, such as schooling, housing, or healthcare fees. Physical accessibility implies that food should be accessible to all, including vulnerable people for whom it may be difficult to procure food individually. Adequacy means that food must be safe, satisfy dietary needs, and harmonise with the culture and preferences. For example, some edibles are energy-dense but poor in essential nutrients, thus mitigating the feeling of hunger but raising the risk of obesity, nutritional deficiencies, and related illnesses. In that case, food is not adequate.

Food, nutrition, and their human rights implications

As the delegations involved in the ICESCR drafting underlined, the right to food is a prerequisite to the rights to life, dignity, and the realisation of every other human right. Adequate nutrition is indispensable to physical and mental development. If proper nutrition is not accessible to everyone, substantive equality - access to equal opportunities and outcomes - is inviable. Malnutrition, mainly at an early age, can cause cognitive and growth impairment, psychological dysfunction, impaired immune response, and diverse non-communicable diseases. Thereby, malnutrition hinders learning capacity, thus increasing the risk of school dropout, reducing opportunities for dignified labour and an adequate standard of living. Malnutrition also hampers the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health, and its effects can be intergenerationally transmitted. Additionally, the physical and cognitive potential lost due to early-onset malnutrition is unrecoverable. Therefore, hunger and malnutrition set individuals in a position of substantive disadvantage that impedes their way out of poverty circles, and their enjoyment of opportunities and human rights.

Due to its intrinsic link with every human right, the right to food transcends the perceived rift between civil and political rights and economic, social, and cultural. In the face of the transversal nature of the right to food, jurisprudence, policy, and institutions often show an ambivalent attitude: while endorsing equal access to adequate food, they also support initiatives of privatisation, liberalisation of trade, agriculture, finance, and cuts in public expenditure that encumber the right.

Public policy obstacles to the human right to food

The main findings of the study are that the policy obstacles in realising the right to food in Colombia are linked to: outsourcing the state’s obligations towards the right to food, centralisation dynamics, impaired public participation, and a reductionist approach to food and nutrition policy.

Outsourcing the state’s obligations towards the right to food

The state aims to fulfil its obligations towards the right to food through: (i) increasing the quantity of food available in the market via extensive production and imports; (ii) food and nutrition aid programs addressed to people considered vulnerable. The state outsources the aid programs to third entities, many of them for-profit. Primary and secondary data revealed that corruption inside these programs is frequent, and outsourcing aid delivery creates conditions that favour diverse forms of corruption. The most frequent corruption varieties related to food and nutrition assistance are:

- corruption in the assignation of tenders and contracts;

- misappropriation of public funds;

- delivery of low-quality, ultra-processed, expired, and even rotten foods;

- Massage of public figures to justify the efficiency of the assistance programs and keep them attracting international cooperation funds.

Centralisation dynamics

The study identified three trends of centralisation. First, centralisation in decision-making, as most policies and programs are formulated in the capital and the main municipalities, then reproduced in the other territories. Hence, the action plans are decontextualised, inefficient, and often violate the cultural heritage and local economies. Second is the centralisation of food supplies, as the main municipalities concentrate most foods because small and dispersed territories are not attractive to suppliers. In contrast, large food industries successfully enter the small markets of remote territories with ultra-processed, nutrient-poor staples at low cost. Subsequently, small territories, many already impoverished and marginalised, turn into food deserts with low availability of adequate foods and impaired economic access. Third, centralisation of assistance refers to the fact that the aid does not reach many dispersed communities of difficult access, so uneven distribution enlarges pre-existing inequalities.

Impaired public participation

After analysing the interview results in the light of the literature review (see the thesis bibliography for the complete references), this study found that the practice of outsourcing public programs enlarges the distance between civil society and responsible institutions. One tender to the following, the program passes from one operator to another. There is no space for the right-holders, who live the programs, to point at their problems, monitor strategies, evaluate, and propose solutions. Concurrently, participation is undermined by a crisis of trust in public institutions derived from repetitive corruption scandals, a lack of platforms for effective participation, and scarce education on constitutional mechanisms for civic participation.

A reductionist approach to food and nutrition policy

The triangulation between the interview results and the literature review revealed transversal links between the obstacles found and the food and nutrition security approach to policy. In Colombia, as in many other countries, food and nutrition policy and international cooperation efforts to fight hunger focus on attaining food and nutrition security, defined as the condition by which every person has permanent, sufficient availability and access to safe, nutritious, and culturally acceptable food under conditions that permit proper biological use for an active and healthy life. Such is the goal of Colombia’s food and nutrition policy, the National Food and Nutrition Security Policy, which orients all the territorial policies and programs in the matter.

The food and nutrition security-oriented approach is problematic for three reasons. First, it focuses on supplies to ensure food availability, access, and consumption to every person. A focus on personal food availability, access, and consumption is limited to the private sphere of food. It overlooks that food is a process that goes from collective production, transformation, exchange, and distribution of food to individual consumption and use of nutrients. An integral rights-based approach to policy upholds both food and nutrition security (person/household level) and the rights of the groups involved in the food processor to participate in it in dignity and sustainably decide the system to do so. Second, by focusing on the private sphere, the food and nutrition security approach tends to understand the resolution of hunger as delivering supplies to individuals categorised as vulnerable rather than as a legal obligation of states under international human rights law. This interpretation prompts a purely assistance-oriented approach that does not allow identifying and tackling the structural roots of hunger. The assistance-oriented approach to policy appears to favour the outsourcing of public programs, which, in turn, seems to foster diverse forms of corruption. Third, food and nutrition security, unlike the human right to food, is not a juridical term. Therefore, it does not set out clear obligations to the state, and its implementation remains at the discretion of the government.

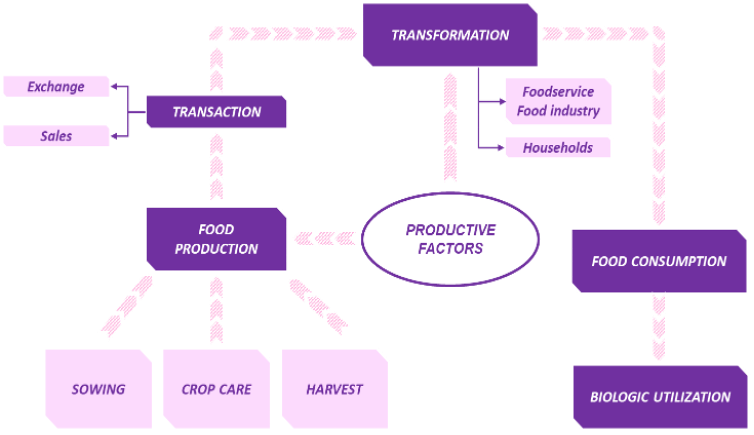

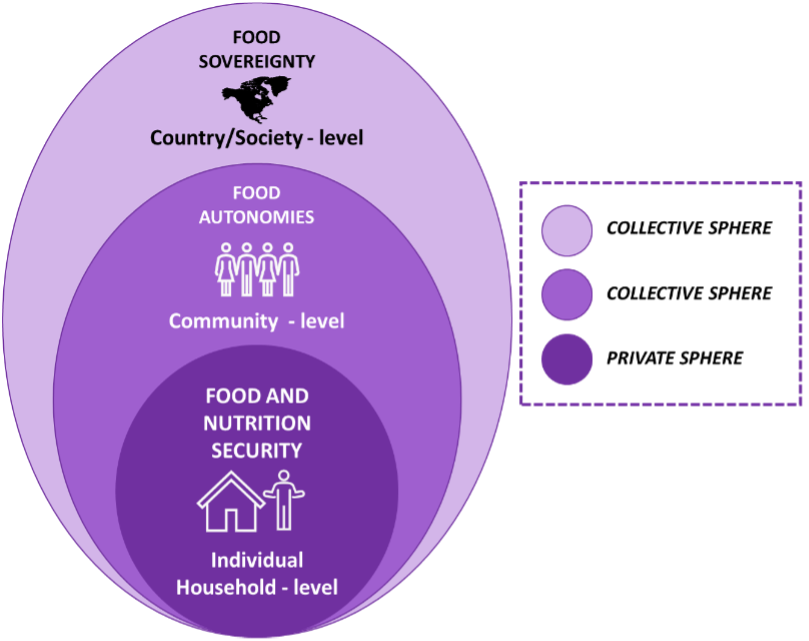

The results of the thesis prove that the conceptual model Food Process and Standards of Social Realization of the Right to Food is a useful tool in developing policy guidelines to: (i) uphold the rights of individuals, homes, communities, and the country to sustainably procure adequate food and decide the system to do so; and (ii) redress the elements of the food process that are infringed by each of the obstacles identified. The model recognises food as a process, analyses its components, and acknowledges its private and collective spheres, proposing three scales of social realisation for the right to food: food security, autonomies, and sovereignty (see figures 1, 2). Therefore, the food process model is the conceptual framework of the policy recommendations stemming from this research.

Figure 1. The Food Process. Adapted from Scheme No. 3 of the Second Report on the Situation of the Right to Food in Colombia of Morales & PCDHDD (p. 14) and Figure 1 of the Fourth Report on the Situation of the Right to Food in Colombia of FIAN (pp.16-17)

Figure 2. The Social Standards of Social Realization of the Right to Food. Adapted from Scheme No. 1 of the Second Report on the Situation of the Right to Food in Colombia of Morales & PCDHDD (p. 20) and Fourth Report on the Situation of the Right to Food in Colombia (p. 43)

Conclusions

The thesis concluded that overcoming the identified policy obstacles requires the construction of territorialised participation platforms that: give voice and vote to all the stakeholders; enable the users of public programs to monitor, evaluate, and propose adjustments to the programs; and allow every right holder to partake in the whole policy cycle (from problem identification and policy formulation to adjustment, passing through implementation, monitoring, and evaluation).

Ensuring citizen participation implies overcoming the purely assistance-oriented approach that sees citizens as beneficiaries of programs and not as right holders and policy allies with the capacity to look after public strategies’ effectiveness and sensitise their communities. International cooperation agencies might play a decisive role by conditioning funds for the construction of territorialised, evidence-based mechanisms for full participation and justifying the impact of food and nutrition interventions through specific indicators that measure the impact of each program on the national nutrition figures. The international cooperation sector can provide technical support to implement these changes.

The practice of outsourcing public programs meant for the implementation of public policy hinders participation. Full participation is pivotal for institutional accountability and planning interventions contextualised to the needs of each territory. Profit-driven parties cannot conduct the programs meant to implement the public policy because their priority is profitability over human rights. In contrast, the State has binding duties toward human rights, so its actions must be motivated by its legal obligations, which entail a moral bound to human dignity.