Reframing Migrants and Refugees’ Integration Policies: A Multi-Level Governance Approach

Table of Contents

- Theory of multi-level governance

- The multi-level dynamics of migrants and refugees integration policies

- Defining processes

- Conclusion

Migration, and the governance of migration, have become one of the most critical issues in our global world, occupying a central position in the political debate of many countries. In the past years, authors and scholars have focused on the political response to migration and the possibilities of inclusion granted to newcomers. However, only very few studies on migration and integration policies were carried out from multi-level governance (MLG) perspective.

The present analysis focuses on how the issue of integration is addressed at different levels of governance. The purpose is to investigate whether and how these levels interact in the development of policies. In fact, even though the responsibility for integration policies lies primarily with the States, directives to guide them are present both at the global and regional levels. The first part of the article provides an overview of the theory of multilevel governance and the conceptual definition of this term. The second part uses such a concept to define the process of policymaking in the field of integration.

Theory of multi-level governance

Multi-level governance connotes a relationship among apparently unconnected but in practice interdependent authority structures that can influence each other in addressing a commonly perceived problem. It has the potential of connecting both territorial (supranational, national, sub-national) and jurisdictional dimensions (determined on the basis of their functions), challenging the traditional boundaries among vertical and horizontal levels of governance.

Being one of the most innovative research themes in social policy, the literature on multi-level governance has intensively grown in the past years, leading to attempts of general theorisations. The 2003 work by Marks and Hooghe is a good example of this trend. The authors identified two types of MLG, which describe two polar ideal types. Type 1 resembles a traditional federal system: authority is allocated across a limited number of non-intersecting levels, with general jurisdiction over a given territory or a given set of issues. Type 2 Multi-level Governance consists of a set of special-purpose jurisdictions that carry out specific tasks. They may overlap, operate at various territorial scales, and tend to be flexible.

The application of the multi-level governance concept to the field of migration is a recent discovery for scholars. To date, it has been mainly used to explain the transition of responsibilities toward local and regional authorities, while the observation of a shift toward supranational levels has often been limited to the European context. Geddes and Scholten, for instance, analysed patterns of Europeanisation of immigration policies.

They distinguished between three patterns: centralisation, in which the primacy of the EU measures determines a loss of control for nation-states; localisation, where the nation-state is willing to cooperate with the EU without losing power; a form of multi-level governance, where there is no clear dominance of one level over the others and governments cooperate with the EU.

In addition to the three patterns of Geddes and Scholten, Scholten and Penninx identified a fourth pattern: the decoupling, which consists in the absence of any policy coordination between levels. National and European policy interests are not always aligned with migration governance; thus, conflict can arise. Few attempts have been made in considering the role of the global level in migration and asylum policies, despite states calling for a greater UN involvement.

The multi-level dynamics of migrants and refugees integration policies

One of the major shortcomings of the MLG and migration research is the lack of a holistic analysis of migrants’ and refugees’ integration policies. In order to have a full comprehension of integration processes, it is important to consider all the levels of governance involved in the area of policymaking, observing how they conceive integration, what each of them is willing to do to achieve it, and for whom are integration policies meant. Furthermore, by adopting a MLG perspective, it is possible to observe how levels intersect, interact and influence each other on issues of policy development.

An example of this can be drawn from the analysis of the policymaking activities of one of the most successful European countries in terms of integration policies: Portugal. In 2019, Portugal approved the National Implementation Plan of the Global Compact for Migration (GCM). It is the first plan in the world adopted to implement the GCM at the national level. The document entered into the national system as part of a broader tradition of the integration of migrants. By affirming the importance of cooperation with key international partners, Portugal adopted the ‘whole-governmental and society approach’ advocated by the GCM.

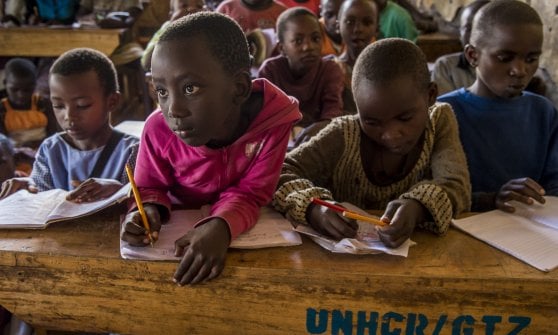

Moreover, the third axis of the Plan addresses the promotion of immigrant reception and integration and introduces measures in line with Objective 16 of the Compact. Its implementation measures aim to ensure that migrants “have a documented status, promoting family reunification, favouring mastery of the Portuguese language, the schooling of children and young people, and the education and vocational training of adults, improving the conditions of housing, health and social protection, and encouraging their integration and civic participation.”

With the implementation of the GCM through this plan, the Portuguese system seemed to move forward with the socio-economic understanding of integration that generally characterizes its policies. However, looking at the significant advances reported after one year of implementation of the National Plan, most of the measures actually implemented are again related to the accession to the labour market.

Defining processes

Another interesting exercise consists in confronting the relationships between policy frameworks with the different patterns of multi-level relations and types of MLG previously observed. An analysis of this kind will have to take into account governmental actors’ representatives of the global, regional, national and local levels, such as the UN, the EU, Portugal and the city of Lisbon. Thus, the application of Geddes and Scholten’s framework will be expanded, trying to analyse and define new and broader patterns.

Looking at the global level, for example, the UN seems to function as a wingman. It assists States and other stakeholders in pursuing their objectives, harmonizing matters and intervening when certain areas are constrained. For this reason, the UN’s activities could be associated to a MLG pattern. Furthermore, in the two Global Compacts, the UN mainly plays an orchestration and coordination role, with the purpose to avoid overlapping in rulemaking. This should amount to a type 1 MLG; however, the reality looks more like a type 2 MLG. The new model of international migration and integration policy proposed in the Compacts, in fact, tends to leave the hierarchical Type 1 of MLG behind in favour of a parallel and mutual connection with State, local and non-state actors.

As for the role of UNHCR in relation to the EU, it results that despite heavily relying on EU funding, UNHCR has a strong source of authority that enables it to provide a counterweight to many EU activities, in particular those related to the integration of refugees.

At the EU level, migration-related Directives might signal a top-down centralist model of integration, mainly because of the binding effect they exercise on States. However, many of these directives are the result of vertical-venue shopping, meaning forms of lobbying for policy measures at the national level. This fits the localist pattern. Furthermore, the various EU non-binding measures, which are softer or more open coordination methods, resemble a Type 2 of MLG. These measures can influence national policymaking. For example, the 2015-2020 Portuguese Strategic Plan for Migration, which annexed integration to a broader migration management strategy, was explicitly aimed at harmonising with European standards, while the adoption of the Municipal Plans for Integration was inspired by the European Agenda for the Integration of Third-Country Nationals of 2011.

Finally, the Portuguese case displays a tendency of the central state to coordinate the national activities of integration through a whole-of-government approach and a holistic perspective. The High Commission for Migration is the public institution under the remit of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers responsible for the integration of all migrants. It plays an important function as a bridge between different ministries and as a coordinator of all the integration activities. In particular, the Commission coordinates the National Migrant Support Centers for the Integration of Migrants, the Local Centers to Support Migrants’ Integration, the Support Unit for the Integration of Refugees and a series of programmes, such as ‘Portugues para todos’ and ‘Programa Escolhas’. It also manages many EU fundings for integration, such as the Asylum Migration and Integration Fund.

The centrality of this public institution and the mechanism of reception and integration suggest the presence of a centralist top-down relationship between the national and the local level. Observing the role of the city of Lisbon closely, it emerges that, although the municipality started moving in favour of migrant integration even before national policies were developed, today it is mainly relegated to forms of cooperation with the offices of the High Commission for Migration. Lisbon’s own initiatives, such as the Municipal Plans for Integration, are to be understood as responding to a call expressed by the central state for the realisation of local strategies that complement the responsibility and expertise of the Central State in regard to some specific issues. However, despite mainly having implementation functions, the city of Lisbon is part of the Council of Migration, which participates in the decision-making process of the ministerial council and connects with supranational levels through international city networks. This suggests the possibility of a multi-level governance pattern.

Conclusion

To conclude, considering all the relevant levels of governance, their roles and interactions, it seems that there is no real unidirectional trend driving integration policies upwards or downwards, and it is difficult to identify a level that dominates over all the others. Rather, the increasing complexity of relations between levels can be observed, and none of these can be connected to a single ideal type with certainty. However, looking at the overall picture, it results that, given the absence of a clear centralist and localist dominance in this field and the existence of a common general understanding of the areas in which policies of integration should apply, it could be possible to talk about a system of multi-level governance. Research on MLG of integration policies needs to be expanded to support such hypotheses. New avenues of research can be opened by considering, for example, the role of private institutions, the public-private partnerships in the field of refugees and migrants’ integration, and the potential for comparison.