The Complex Reality of Becoming an Adult for Young People: Why 18 May Not Be Enough?

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Marriage & Having Children While Your Brain Has Not Fully Matured

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

Introduction

Moving from one stage of life to another varies greatly depending on the developmental period in question, where each stage is characterized by unique challenges and expectations that individuals are expected to navigate and overcome. However, the first 18 years of life are

when people experience the most significant emotional, cognitive, and biological changes, where their brains are constantly reshaping, and the hormones in their bodies are constantly in flux. Taking into consideration these factors, numerous psychological studies have focused on adolescence as one of the most critical periods of development during these 18 years. Moreover, this stage attracts the attention of parents, teachers, and professionals alike. Society often focuses on the difficulties of adolescence, as reflected in the media and everyday discussions. Yet, far less attention is given to what follows the moment one turns 18, and is legally labeled an adult, facing the responsibilities that come with that new identity.

The new challenges and decisions young people face are indeed numerous, such as finishing school, leaving home, and finding a full-time job (Furstenberg, 2015). As the guidance and structure once provided by families, schools, and youth-oriented services diminish, emerging adults must increasingly depend on their own skills and judgment in a less structured environment. Those who possess adequate financial means, social support, and personal maturity are more likely to make positive life choices and follow a successful path during this stage. In contrast, individuals with fewer resources or those facing physical, mental, or intellectual challenges may encounter greater difficulties, leading to less favorable outcomes in areas such as education, employment, relationships, and overall health (Wood et al., 2017). Once they become 18, it doesn't matter the resources or the conditions that they grew up in; by law in most countries, they are considered adults, which officially allows them to get married, have kids, and make many other decisions that they did not have before, decisions that can change the trajectory of their lives and those of others.

But what does science tell us? Are these young adults cognitively and emotionally ready to think carefully and make such important decisions? This article has the goal to discuss this topic and argues that although society legally defines 18-year-olds as adults, neuroscience shows that critical brain systems involved in judgment, impulse control, and long-term planning are still developing. While young adults possess many adult-like cognitive abilities, their decision-making tends to be more context-dependent and more susceptible to stress, emotion, and social influence than that of fully mature adults. This does not mean that 18-year-olds are incapable of making important decisions, but it does raise questions about their readiness to make such decisions consistently in high-stakes situations. Therefore, major life choices such as marriage and having children require careful, deliberate consideration and should not be made under possible emotional strain or social pressure.

Marriage & Having Children While Your Brain Has Not Fully Matured

According to the literature, being legally considered an adult at age 18 does not guarantee that the brain systems responsible for effective decision-making are fully mature. Arain et al. (2013) found that the development and maturation of the prefrontal cortex occur primarily during adolescence and are largely completed by the age of 25 years.

The development of the prefrontal cortex is very important, as this region of the brain helps accomplish executive brain functions and supports the ability to make thoughtful and appropriate decisions during challenging life events. Consequently, as prefrontal cortex networks mature, young people generally become better equipped to evaluate consequences, think critically about competing demands, and inhibit maladaptive responses, supporting more adaptive, goal-directed behavior. In contrast, when prefrontal regulatory systems are still developing, a normal feature of adolescence, or when their maturation is disrupted, individuals may experience greater difficulty with judgment, impulse control, and stress regulation, which can increase vulnerability to risk-taking behaviors and emotional dysregulation. For instance, adolescents often take risks in relatively safe settings, using their brain circuitry to build skills for handling more hazardous situations. However, they may continue to engage in risky behaviors even when they recognize the potential danger (Giedd, 2006). Therefore, some of the young adults place a greater importance on positive experiences while minimizing the impact of negative ones. This tendency can increase their likelihood of taking risks, such as driving recklessly, having unprotected sex, or using drugs (Arain et al., 2013).

This developmental imbalance becomes especially evident when adolescents and young adults experience strong emotions such as fear of rejection, a desire to fit in, or excitement from taking risks; they often struggle to think clearly about the consequences of their actions or to make sensible decisions. In fact, adolescents and young people tend to rely more on emotional regions of their brains when interpreting others’ emotions, leading to more impulsive responses than logical or deliberate interpretations. Since adolescents and young adults depend largely on the emotional regions of their brains, they may struggle to make decisions that adults would consider logical and appropriate. Decisions such as marriage or raising children require empathy, patience, and long-term thinking, capacities that research shows are still developing in individuals between the ages of 18 and 25. Marriage and parenting require exactly the skills the prefrontal cortex supports: long-term planning, emotional regulation, impulse control, and stress management. Furthermore, from an Eriksonian perspective, early marriage may prematurely push individuals into the stage of intimacy versus isolation before the successful resolution of identity versus role confusion, increasing the likelihood of relationship instability and psychological distress (Erikson, 1968).

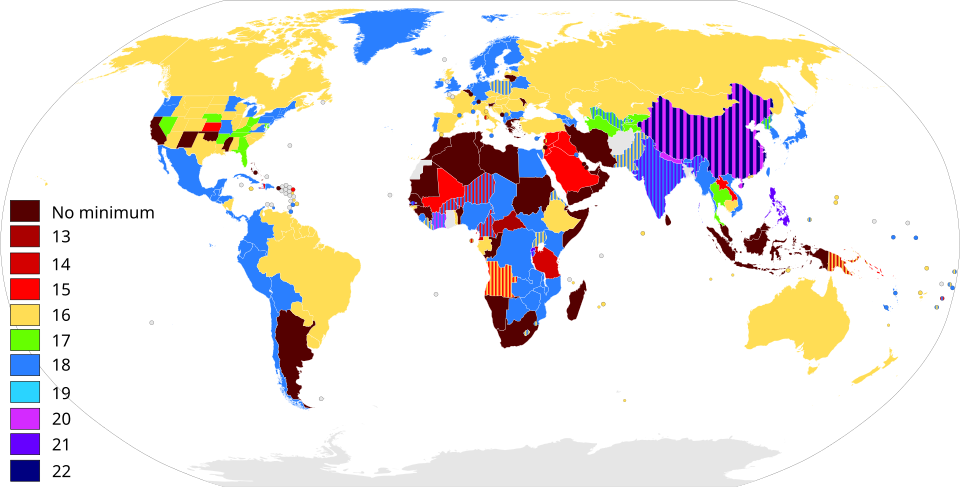

However, despite these facts, in many countries around the world, as seen in the figure below, marriage is allowed with judicial consent even for those below 18 years old.

Although this practice continues to decline globally, approximately 650 million girls and women were married before their 18th birthday, as reported by UNICEF in 2021, indicating that the Sustainable Development Goal target of eliminating this harmful practice by 2030 is unlikely to be reached. While the age for first marriage has increased around the world, according to the latest data from the World Bank, females are still more likely to marry before the age of 25. Marriage, when your brain is not fully developed, comes with consequences, as seen above. When you're between these ages, you tend to overestimate positive experiences, which, in this case, can also be when choosing a partner; you tend to appreciate only good qualities without thinking carefully about other attributes. The tendency to make decisions based on emotions rather than thinking carefully is higher, which can lead to deciding to marry someone based solely on your emotions without evaluating all other aspects of that decision. This can occur without fully considering important factors such as financial readiness, the effects of that decision on your career, or the impact on personal and professional development. Studies have shown that young marriages have implications for the mental health of young women and men, such as depression, anxiety, and psychological distress, because of a lack of personal and financial resources to deal with marriage responsibilities (Vikram et al., 2025). Evidence shows marital success (measured by marital survival and quality) generally improves with age at first marriage, up to the early to mid-twenties. Marrying earlier increases the likelihood of divorce, demonstrating that earlier marriage can causally worsen marital stability (Garcia‑Hombrados & Özcan, 2022). While early marriage poses risks, not all young adults experience negative outcomes. Studies indicate that success is possible under certain conditions. Research suggests that young adults aged 18 - 25 years old can and do succeed in marriage when some of the key social conditions are present, such as financial stability, strong social support, shared values, relationship quality, and adaptive processes (Green, 2023).

Moreover, some young people at this age are not only trying to marry but also have children, all this while they're trying to become financially stable, build a career, and develop an identity. In comparison, some studies show that this decision might not be the best one at this age. A longitudinal study found that early parents (first birth < 20) report higher levels of depressive symptoms in young adulthood (around age 29) compared to those who became parents later, or non‑parents. The depression is largely explained by factors like financial strain, fewer resources, and a weaker sense of personal control among early parents (Falci, Mortimer, & Noel, 2010). Moreover, a survey by Home-Start UK in 2024 revealed that young parents feel more socially isolated than older parents, and another study found that early parenthood can disrupt the transition to adulthood, which affects the educational and professional development trajectory, and can increase long-term emotional and economic stress (Grundström et al., 2024). However, it is also important to note that some young parents successfully navigate these challenges, building stable careers, strong family bonds, and fulfilling personal lives, demonstrating that early parenthood does not inevitably lead to negative outcomes. For instance, young adults who have supportive parents showed fewer depressive symptoms and better overall well-being than those with less supportive environments (Jensen et al., 2024), a factor that indirectly supports their own parenting capacity later. Also, state support is an important factor in this case; a study revealed that childcare subsidies, tax credits, and cash assistance can help reduce financial stress for working and parenting families (Maguire‑Jack, Johnson‑Motoyama, & Parmenter, 2022), making it easier for young parents to care for children.

Recommendations

To prevent early marriages and the consequences that come with that decision, as recommended by the Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), marriage below the age of 18 years should be prohibited in all countries around the world. Countries known for their high quality of life, such as Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, have followed this recommendation and no longer allow marriage under 18; therefore, it would be essential for other countries to follow the same steps. Governments and policymakers should take neuroscientific evidence into account when designing laws related to marriage, parenthood, and other high-stakes life decisions. Moreover, governments should prioritize supportive interventions rather than punitive measures and should offer childcare subsidies, parental leave policies tailored to young workers and students, and educational and career-reentry programs. These measures would not restrict autonomy but rather promote informed and reflective decision-making during a period of ongoing brain development.

Parents also play a crucial role in the decision to get married and in providing a safe environment for their teenagers and young adults to talk about such topics. The authors found in one study that parental discussions about school performance, friendships, and personal issues are strongly associated with delayed marriage (Paul et al., 2023). The review of 20 studies shows a consistent link between parental education role (as educators) and adolescent behavior that resists early marriage. The authors argue that parents acting as educators at home, not just sending children to school, but actively talking, guiding, and teaching, is critical for preventing early marriage (Idawati et al., 2023).

Schools also play an important role in educating young generations about their bodies and how they are developed; therefore, schools might introduce a sex education program as part of their curricula. In a study, the authors analyze a historic reform in Swedish sex education (1940s–1950s) and show that school-based, comprehensive sex education had long-term effects on marriage timing (Lazuka & Elwert, 2023). Furthermore, schools and universities should expand life skills education beyond adolescence to include emerging adulthood; they should develop programs that focus on: financial literacy, long-term planning, relationship education, emotional regulation, and stress management. Another study has revealed that a multi-component intervention (youth info centers, peer education, mass media) significantly reduced early marriage and early pregnancy, and increased school retention (Mehra et al., 2018). Free counseling services should be expanded for young adults considering marriage or parenthood. Premarital education programs grounded in psychological research can help individuals assess relationship readiness, communication skills, and conflict-management strategies, reducing the likelihood of later marital dissatisfaction or divorce.

Conclusion

According to this perspective, it becomes clear that transition into adulthood is a process that requires time, and that extends beyond the legal age of 18, as neuroscientific evidence suggests that brain regions responsible for judgment, emotional regulation, and long-term planning continue to develop into the mid-twenties. This has significant implications for important life decisions such as marriage and parenthood, which require exactly the skills mentioned above. Research shows that marrying or being a parent at a young age is linked with increased risks, including emotional distress, financial strain, disrupted education or career paths, and higher marital instability. However, positive outcomes are possible when strong social support and resources are available. The findings suggest that there is a disconnection between the legal definition of adulthood and biological development, suggesting the need for policies, education, an familty support system that promote reflective decision making during adulthood.