The international protection and the Italian asylum system: an analysis of Security Decrees

Table of Contents

- Goal

- The path of migrants toward asylum

- The European Commission intervention on asylum matter

- Asylum in Italy

- The impact on status determination commissions: findings from Territorial Commission of Padova

- The debate over Salvini Decrees

- Conclusions

Goal

The aim of this work is to analyse the international protection recognition, a right granted by States to protect persons fleeing from their country, and the impact that migration policies have been having on the body responsible for the recognition of protection in Italy. The numeric references, gathered at the Padova Commission and on the portal of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, are approximate and serve as a general indication.

The path of migrants toward asylum

Migratory movements have been characterizing society for thousands of years. And while people flows modify in ways and peculiarities over time, data testify that the trend has been steadily and slowly increasing since the late 1990s.

Among migrants, there are people who leave their country (either by personal choice or constraint) to flee from situations that would be a danger for their safety and security and, therefore, when they reach the destination, apply for protection. The asylum concept has religious roots; it was indeed meant as a holy place and thus who came there was safeguarded. Since then, it has developed according to the thought of the time, to the point of, thanks to the revolutionary and freedom ideals’ contribution, disengaging from the physical concept of place and assuming a true personalistic and legal connotation: nowadays, asylum is a human right recognized by States to protect those who flee from oppressive and dangerous environments. Jurisdiction is upon the hosting country that intervenes in the assessment and recognition process of the right.

At the European level, once protection has been required, the specific process to go through varies from one country to another in time and manner. The so-called “international protection” offers two options: the refugee status, coined by the Geneva Convention in the UN context, and subsidiary protection, set up by the European Commission. Moreover, each country that has adhered to the international protection institute has the option to introduce an additional form of protection and determine the competent body of assessment and recognition.

According to the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, the right to asylum (art. 18):

shall be guaranteed with due respect for the rules of the Geneva Convention of 28 July 1951 and the Protocol of 31 January 1967 relating to the status of refugees and in accordance with the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

The premise of this topic is that the term “asylum” is often intended as “refuge”. Instead, the status of refugee is just one of the options available when someone is asking for protection. The status of refugee is regulated by the 1951 Geneva Convention, which states:

the term “refugee” shall apply to any person who: […]

[o]wing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

The term refuge thus refers to cases in which there is persecution and when this is exclusively linked to the aforementioned reasons: race, religion, nationality, membership to a particular social group, and political opinion.

The European Commission intervention on asylum matter

Compared to the situations enshrined in the Geneva Convention, asylum is a broader institute, as it includes other risking conditions to a person, which are separate from persecution for the above reasons. At regional level, in 2004 the European Commission adopted Directive number 83 -better known as Qualification Directive- in order to fill the gaps left by the 1951 Convention. The Directive’s article 15 indicates as a prerequisite for recognizing the so-called “subsidiary protection” the presence of serious harm upon return to one’s country. Such “serious harm” can be: condemnation or death penalty, torture or other inhuman and degrading treatment, a serious threat to life or person due to indiscriminate violence in armed conflict contexts.

In addition, in 2001 with Directive number 55, the European Commission introduced the “temporary protection”, with the aim to manage “a mass influx of displaced persons” and to balance “efforts between member states in receiving such persons and bearing the consequences thereof”. This form of protection had never been applied, until recent events in Ukraine: in March 2022, the European Union Council activated the temporary protection, in response to the high number of displaced Ukrainian citizens.

Asylum in Italy

In Italy, the right of asylum is recognized at article 10 of the Constitution. In 2002 a law set up the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ bodies, the “Territorial Commissions”, in charge of the assessment and recognition of international protection. In addition to refugee status and subsidiary protection, in 1998 the Consolidated Immigration Act (Testo Unico Immigrazione, TUI) created a form of protection for humanitarian reasons, stating that “objective and serious personal situations” could not “allow for the removal of the foreigner from the national territory”. The so-called “humanitarian protection” was a broad form of inclusion, as it considered a wide range of options: “serious reasons, in particular of humanitarian nature or resulting from national and international obligations”. Data of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, in fact, show that the so-called “humanitarian protection” had 20-25% of recognition among the positive responses to international protection requests. When conditions did not satisfy refugee status nor subsidiary protection, those other considerations could bring to protection for humanitarian reasons.

In October 2018, the Security Decree of the Minister of Internal Affairs Salvini abruptly changed direction in the national system of protection; specifically it had the effect of suddenly reducing the access to protection’s possibilities. The humanitarian protection was abolished, and it was substituted by the label “residence permit for special cases”. The immediate problem was its ambiguity and vagueness which created a regulatory vacuum that provoked relevant shocks in the Italian migration system. The new permit recognized was restricted to article 19 of the TUI (which prohibits expulsion or refoulment to whom would risk persecution or torture; to minors under 18 years old; to whom has a residence permit; to cohabitants with relatives within the second degree or spouses; to women who are pregnant or in the first 6 months after childbirth), deleting several conditions that previously granted humanitarian protection. Salvini’s “special cases” brought to a dramatic fall in the numbers of inclusion of asylum’s seekers, from the 20-25% during humanitarian protection-phase to only 1% of recognition.

In October 2020, two years after the first Security Decree, the new Minister of Internal Affairs Lamorgese published a new Security Decree that widened the inclusion possibilities. The so-called “special protection” newly introduced has first of all the aim of safeguarding private and family life: when evaluating asylum’s request and when rejecting the two forms of international protection, special protection may be guaranteed when effective family ties on the territory, social integration that includes level of language and/or a job, duration of stay in Italy, non-existence of family, social, cultural ties in the country of origin are demonstrated. The new situation has immediately led, among positive results, to an increase in the inclusion rate for Italian protection, from 1% of Salvini special cases to 2%, calculated at the beginning of 2021: considering the introduction of the Decree in October 2020, the hope is that the impact will be more evident in the upcoming years.

Therefore, today when an application for international protection is made, the Territorial Commission responsible for the geographical area evaluates refugee status; if the requirements are not met, it hypothesizes subsidiary protection; if the outcome is negative, the Commission officer may propose special protection as a residual form. As an alternative to the Territorial Commission, the police headquarters (Questura) are also authorized to recognize special protection upon the Commission's favourable opinion.

The impact on status determination commissions: findings from Territorial Commission of Padova

During a curricular internship held at the Territorial Commission of Padova from April to June 2021, I realized how closely connected migration and people’s lives are to politics: a response depends on normative rules set by governments.

Analysing data, the impact of 2018 Security Decree on Territorial Commissions’s work and consequent results were relevant. First of all, in terms of delays in interviews and responses, as the amendment of migration policies provoked slowdowns in the procedures. It then proved difficult to apply an unclear law that lent itself to different interpretations, both for Commissions officers and for applicants whose applications were suddenly denied despite the fact that their stories were similar to those that, during the humanitarian protection phase, guaranteed positive outcomes. The situation then brought to an increase in appeal numbers resulting in pressure on the judicial system.

Another area that deserves to be analysed is the mechanism of renewal, that is the confirmation or revocation of the previous protection’s recognition. It is automatic for the refugee status and the subsidiary protection, except in cases when events have significantly changed. Both humanitarian protection and the current special protection last for two years; the Salvini’s special cases expired after only one year: these time inconsistencies caused further problems in the bureaucratic processes.

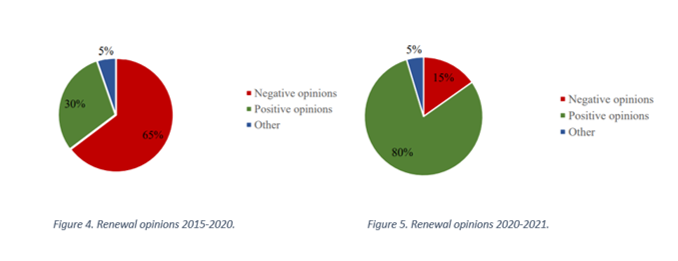

At the Padova Commission, 65% of special cases (Salvini Decree) renewal requests were denied, as the numerous possibilities for inclusion guaranteed by humanitarian protection did not meet the tight mesh of special cases. On the other hand, only 20% of the opinions were negative with respect to Lamorgese’s special protection renewals, reflecting the evidence that the meshes were once again widened.

The debate over Salvini Decrees

A note from ASGI (an association on legal studies on immigration) had raised concerns about the Salvini Decree, whose draft already had elements of unconstitutionality: the association stated that the repeal of article 5.6 of the TUI (which prohibits the deportation of those who incur danger in their country of origin) is an unconstitutional act in the face of articles 2, 10 and 117 of the Constitution (on inviolable human rights, the right to asylum, and the competence of the state in immigration matters). Another element of unconstitutionality relates to the detention of applicants after identification, a violation of articles 2, 3, 13.3, 117.1 (i.e., inviolable human rights, equality before the law, personal liberty, state jurisdiction over immigration and asylum) and article 31 of the Geneva Convention (on not punishing those who enter illegally if they turn to the authorities and/or seek protection) because it sanctions with deprivation of liberty the foreigner who is not in possession of travel documents.

The Cassation Court affirmed that the constitutional right of asylum was entirely exhausted by international protection and by humanitarian one too. The Salvini Decree, by eliminating humanitarian protection, left a gap, which was only partially filled by Lamorgese. In any case, uncertainties and inability to pursue a clear line over the years have left loopholes in the regulatory system and dragged in problems that are far from being resolved definitively. The best solution would be to reform the legislation completely.

Conclusions

My internship at the Padova Commission allowed me to witness the arduous path migrants undertake once an application is sent. Indeed, I noted numerous paradoxes within the asylum system and obstacles to its very recognition; as a matter of fact, most of the time migrants opt for this solution, despite their condition does not amount to any of those required by international protection recognition, being it the only and fastest way to have regularity guaranteed. This discouraging reality made me acknowledge the inconsistency of the asylum system in Italy and to realize that those who arrive in the country have no many options but to confront this institute.