The “Security Decrees” I & II and their Impacts on Human Rights: An Analysis of Domestic and International Reactions

Table of Contents

- General framework

- International and domestic reactions

- Implication on the field: between a bad approach and good practices

- Conclusion

Every Italian government since the 1990s has wanted to put its mark on the national migration policies, causing slowdowns, malfunctioning and misinformation. The permanent imperative of “security” has been translated into vigorous enforcement measures within the borders and attempts to externalise borders’ control. Not deviating from this trend, the current legislation on immigration and security was born during the Giuseppe Conte cabinet I, a problematic coalition of two parties that lasted 14 months, from June 2018 to August 2019. During the negotiations to set up the coalition, the two parties, Lega Nord e Movimento 5 Stelle, moving from their respective ideological visions, tried to converge on a few common points, not without disputes and discussions. The two eventually signed a “government contract” of shared positions and goals. As stipulated in the “contract”, two urgent law-decrees were drafted: the “Security Decrees” I and II, entered into force respectively in October 2018 and June 2019. At that time, despite a dramatic reduction in the number of entries, an “invasion alarm” narrative was used to describe the immigration flows.

This article considers the main consequences of the security decrees on a practical level, in the daily life of migrants, especially those unable to understand the Italian law system.

General framework

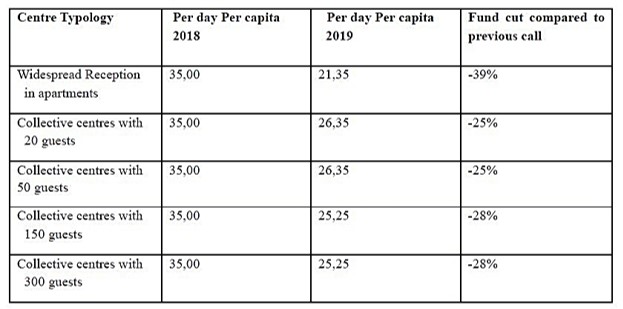

The two security decrees, among other things, amended the Consolidated act of Immigration (Testo Unico sull’Immigrazione). Security Decree I, in particular, repealed the humanitarian protection status, claiming it was used disproportionately by the Territorial Commissions for the recognition of the international protection status. The humanitarian protection status was replaced by different forms of protection, including for medical treatment, for victims of violence or severe exploitation, and for victims of domestic violence. Indeed, Security Decrees I and II changed the entire structure of the reception system. Firstly, they removed any reference to the second-level reception system (SPRAR: the system for the protection of refugees and asylum seekers), which was aimed to integrate migrants into Italian society, through training and internship opportunities. The new dispositions only granted access to “essential” (first-level) reception facilities, provided by Hotspots centres, CAS (extraordinary reception centres) and CARA (reception centres for refugees and asylum seekers). Moreover, the overall system suffered a cut in funding from €35 to even €21,35 per hosted migrant per day (see Table 1). This amount of €35 had been largely criticised by the right-wing political parties, based on a misbelief that the money was given directly in cash to each migrant, while actually it was paid to the authorities running the reception structures.

Table 1 Cuts to the reception system according to the number of migrants (From In Migrazione report “lamalaccoglienaza”)

Security Decree II, articles 1, 2 and 4, are especially interesting. Art. 1 restricts or prohibits the entry, transit or parking of ships in the territorial sea “for reasons of order and security” or when it is assumed that they are “facilitating illegal immigration”. Art. 2 provides pecuniary sanctions, ranging from €150,000 to €1 million, for the captain of the ship “in the event of a violation of the prohibition of entry, transit or parking in Italian territorial waters”. Art. 4 allocates €500,000 for 2019, €1 million for 2020, and €1.5 million for 2021 to combat the crime of aiding illegal immigration and support undercover police operations.

International and domestic reactions

The Security Decrees had worldwide repercussions. Core international human rights actors, including UN experts, UN Special rapporteurs and the European Human Right Commissioner stressed that the decrees had violated international law, for instance, Article 5 and 6 of ICCPR, Article 98 of the UN Convention the Law of the Sea and Article 31 of the Geneva Convention 1951. In addition, National Human Rights Institutions (NHRI), Civil Society Organisation (CSOs) and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) submitted criticisms for the third cycle of the Italian Universal Period Review (UPR). In their shadow reports, international and national actors focused on the migrant’s human rights condition. The most discussed parts have been the relation between Italy and Libya concerning the Memorandum of Understanding, the violations of the non-refoulment principle and the misinterpretation of the “Place of Safety” (POS). In particular, the Proactiva Open Arms, Aquarius, the "Diciotti" case and the Sea Watch case, criticised that Italian legislators prioritised the “security of the border” over human rights protection. Some of their decisions were aimed at hampering NGO and SAR operations instead of protecting people’s life. In particular, in the Open Arms case, the judge of Ragusa underlined that “place of safety” is the place where people rescued at sea is safe and far from mistreatment. However, in the majority of cases, the Repatriation centre (CPR) and temporary facilities (CAS) cannot be considered safe places.

The Security Decrees have provoked a series of domestic reactions. For instance, in his report to the Italian Parliament 2019, the National Ombudsperson for the Rights of Detainees and Persons Deprived of their Liberty stressed the importance of protecting foreign citizens from arbitrariness and the deprivation of freedom, referring to Article 13 of the Italian Constitution and Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights. In addition, Italian judges and lawyers from the Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration (ASGI) considered that the decrees violated the constitutional obligations under articles 10, 13, 76 and 77 of the Italian Constitution. Under these articles, the abolition of the humanitarian protection and the extension on the detention period in Hotspot and CPR is, among other things, a direct violation of human rights.

Implication on the field: between a bad approach and good practices

Apart from the criticism, the Security Decrees I and II have caused a lot of trouble in their application on the field. Evidence showed gaps between the claimed aims of the legislators and the public response of the decrees. For example, the prolonged duration of stay in the Hotspot and detention facilities, intended to enhance security, caused in fact riots in Lampedusa and in other CPRs. The prohibition of including asylum seekers in the registers of residents made their daily activities, such as to open a bank account, find a job or join a sports team, more and more difficult. Various lawyers associated with ASGI and ‘Avvocati di Strada’ started strategic litigations on this point, and the mayors of several cities challenged the prohibition assuming personal signature responsibilities. The courts’ response has been heterogeneous. For instance, the Court of Trento rejected the appeal, while the tribunals in Bologna, Firenze, etc. ordered the registration. On July 9, 2020, the Constitutional Court finally regulated the issue, establishing that the prohibition introduced by the law-decree breached art. 3 of the Italian Constitution (principle of equality) and was therefore null and void.

Another crucial point concerned the tenders for the reception centres. Financial cuts made it easier for big service providers whose primary interest was profit, to win the bid. The abolition of the SPRAR system, transformed into SIPROIMI (protection system for refugees and unaccompanied minors) and the cut in financing inclusion activities pushed migrants to seek income opportunities by joining criminal organisations. According to the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI), a large part of undocumented migrants is expected to join illegal work in the industry or in the agricultural sector. In 2018 the number of workers in agriculture increased by over 40 thousand units compared to the previous year, and 14 thousand of them were foreigners. Urmila Bhoola, the United Nations special rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, visited Italy from 3 to October 12 2018. During her stay she urged the Italian government to effectively prevent the exploitation of migrants in the agri-food sector, victims of illegal hiring, addressing the problem at its roots and recognising all migrants as holders of rights. Indeed, even if a legislative reform has been introduced, the Caporalato system(agriculture labour exploitation) is still a giant problem for Italy.

Civil society, however, never stopped to support refugees and immigrants. For instance, the Italian Waldensian Church, the Evangelical Communities, the Community of Sant’Egidio, the Caritas Italiana and the Migrantes Foundation of the Catholic Church created the “Humanitarian Corridors” project, a legal entry mechanism based on provisions of the EU Visa regulation. Another good practice is the program “University Corridors for Refugees” (UNI-CO-RE), offering refugee students in Ethiopia the chance to continue their academic career in Italy. Started in Bologna, the project now engage 10 Italian universities, including the University of Padova (Program UNI-CO-RE 2.0). Finally, some municipalities, community and civil society groups have launched platforms like Refugee Welcome Italy to receive and assist migrants.

All in all, however, the ultimate goal of establishing a reception system that fully implements human rights is far from being achieved. Priorities should be: informing communities and the public about migration issues and implementing concrete policies likely to grant hope and dignity to those who have lost both.

Conclusion

This study showed that the two security decrees, now laws 132/2018 and 53/2019, have indeed created more instability and insecurity, despite the legislator’s intentions. Migrants have found it even more difficult to achieve daily life tasks and to be included in the Italian society. Due to the cuts imposed on reception policies and especially the dismantlement of the SPRAR system, they are now hindered from applying for jobs and learning the Italian language. Moreover, the current situation of the country confronted with the Covid-19 crisis has forced holders of expired humanitarian permits to enter the “black” market of work. Since the abolition of humanitarian protection, the only figures that have been increasing in Italy were those of invisible migrants working under the threat of organised crime, such as mafia and Camorra. It seems obvious that this approach to migration as a public security issue is not the solution. Migrants need to be treated with dignity, not as pawns in political games.