The Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage: the Economical-Political Blockade and Future Prospects for Reparations against Climate Change Impacts

Nowadays, the entire world is experiencing more and more the increase in frequency and intensity of climate change adverse impacts associated to anthropogenic actions. This subject is today one of the most controversial and global issues of the world because it crosses the human and environmental conditions of the entire planet.

Although the formulation of mitigation and adaptation measures from the beginning of the 1980s, this commitment has proven to be not enough to prevent dangerous climate change related impacts. In other words, the climate change effects that we are not able to adapt and mitigate are now part of the climate change impacts that we can call Loss and Damage (L&D). For more than 20 years, the Alliance of the Small Islands States (AOSIS) has been advocating for a backup plan in case states failed to mitigate and adapt climate change adverse impacts that are now already happening.

In these years, while many scientists urge states to implement new political and economic climate-positive decisions, many populations are already facing global changes that put their health and survival at risk.

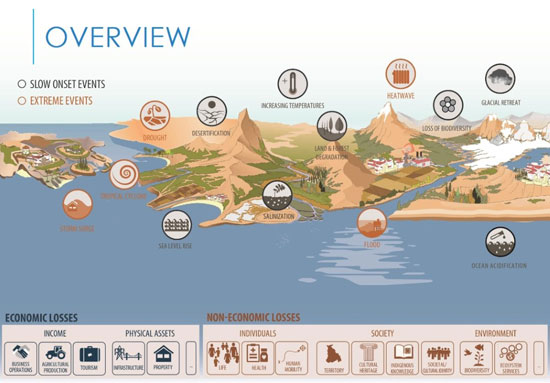

Figure 1: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2017. Source: Online Guide on Loss and Damage.

For addressing L&D, at the 19th Conference of the Parties (COP) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Warsaw, states agreed to the formulation of the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts (WIM). The WIM, reached not without many controversies between developed and developing states, was thought for tackling L&D caused by climate change in those developing countries that have been more affected by its impacts and for addressing both extreme and slow onset events.

Figure 2: Evolution of the Loss and Damage discourse under the UNFCCC.

Its formulation gave the chance to the states to agree on a common principle that implies a support from those countries that contributed the most to climate change (the developed countries) towards those who suffered it more (the poorest countries). In particular, so far, the WIM has focused more on two of its mandates: the enhancement of knowledge and understanding of comprehensive risk management approaches, and the strengthening of dialogue, coordination, coherence and synergies among relevant stakeholders. Under these two functions, the WIM was able to reach two important achievements: the formulation of a Task Force on Displacement “to develop recommendations for integrated approaches to avert, minimize and address displacement related to the adverse impacts of climate change” and the launch of a Clearing House for Risk Transfer that allows beneficiaries to contact directly experts on risk management that are at their disposal for supporting them in reducing risks.

Together with these two mandates, the strong commitment of the AOSIS has managed to get a third mandate included in the WIM which refers to the “Enhancement of action and support, including finance, technology and capacity-building, to address loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change, so as to support countries […]”. Since the late 1980s, the AOSIS has worked together with several NGOs to give a practical shape to this mandate. With its strong advocacy capacity, the AOSIS’s goal has always been to increase the awareness of the international community on L&D and to get recognized the liability of developed countries in order to receive compensation through a tangible L&D financial mechanism.

From that moment onward, many politicians of the most developed countries supported the idea of insurance schemes for addressing L&D produced by climate change. However, it soon became clear that this could not be the solution to the whole problem; insurance schemes are not accessible and affordable to everyone and they can only be used when sudden, unpredictable and infrequent disasters occur.

After that, for the first time, the Paris Agreement underlined the importance to prevent, minimize and cope with losses and damages associated with the adverse impacts of climate change, promising to tackle the issue of L&D. However, it did not include any kind of obligation for the countries to implement actions to this aim. In fact, article 8 states that “[the adoption of the WIM] does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation”.

Since then, no concrete step forward from the international community has been made for addressing concretely L&D. After six years from the creation of the WIM, states parties have not established any tangible or concrete solution for financing and supporting the most vulnerable countries in addressing L&D, increasing the reasons that prevented the WIM from achieving its mandate.

The analysis of the international climate debates shows that the non-fulfilment of the measures promoted by the WIM so far can be associated to the economic and political blockades coming from developed states any time the L&D enters the climate negotiations. In fact, developed countries continue to completely refuse any kind of dialogue that could lead them to admit liability and compensation obligations for the adverse effects of climate change.

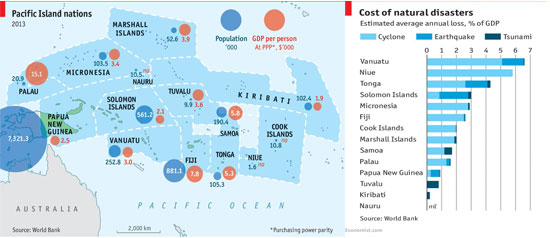

While several states are facing drastic climate change consequences, the WIM remains an important information initiative but without the effective capacities for translating this information in a tangible support. An example of the most climate vulnerable countries of the world is Vanuatu. This country - as many others - is already experiencing L&D and, despite the mitigation and adaptation measures already implemented, the scale of L&D experienced is beyond the state’s capacities. This has proven to have serious consequences towards the local population which livelihood and human rights are increasingly more affected. In particular, an increasing part of the population is frequently forced to move in other parts of the country or outside it, endangering the lives and the well-being of many people. The internal displacement is the cause of many difficulties for the populations involved especially in terms of vulnerabilities, difficulties in the relocation paths, scarcity of resources and conflicts among communities.

Figure 3: The Economist, Mar 17th 2015

Despite the creation of the WIM and despite the global and general understanding of the climate change impacts on vulnerable states, Vanuatu - as example of all the other affected countries - is still facing strong economic and political blockades coming from the developed countries for what concerns financial contributions. The non-advancement in financial and technical terms has left the most affected populations alone in tackling this alarming situation. Vanuatu (as many other countries) frustrated by the constant inaction under the UNFCCC regime, is now taking other avenues that could lead it to more concrete outcomes.

This, connected to the scarce capacity and willingness of the states to dialogue outside the liability and responsibility dynamics have made impossible finding a proper sustainable solution for addressing concretely L&D. It is exactly for this reason that - with different paths and different ways - emerging strategies that can help re-boosting the L&D concept within the international climate regime and unblock the discussion on the issue have arisen.

Among these there are:

- The legal avenue: Acting consequently to the inactivity and ineffectiveness of the international response to L&D, many people have decided to take the legal avenue to obtain concrete remedies. This not only has positive consequences for the individual cases, but it has the power of producing new political debate around the L&D concept. Firstly, the litigation cases push the national governments to change policies or to adopt new ones that are more climate change sensitive. They also can stress the reiterative conduct of a state with the possibility of resulting in compensatory and reparative binding obligations for the harm inflicted by the wrongful conduct. Finally, the several litigation cases against the fossil fuels companies can motivate them to support a liability regime within the UNFCCC framework where all polluters pay rather than having singular litigation cases focused only on some companies.

- The Human Rights Based Approach: it indicates to states that there are already set international and regional human rights obligations and includes climate policies under these obligations, specifically under human rights law. In this way, even without a compensation and liability framework agreed among States parties under the L&D regime, international human rights law gives the opportunity to damaged populations to benefit from a judicial recourse. In this sense, the HRBA provides for a preventive solution that, rather than addressing the violations of human rights emerged by L&D, tries to «tailor the L&D regime to the human rights obligations».

- The National Mechanism for L&D: a pilot project launched by the Government of Bangladesh that will try to address different aspects of L&D. The lessons that will emerge from the national level could help give the opportunity to the international community to be an observer and to increase the understanding on how L&D will be addressed at both the international and national levels.

All these three approaches showed to have the potential to push the international community to react actively towards a more equitable sharing of the responsibilities and burdens of L&D. In fact, the mere formulation of the WIM cannot be considered a sufficient result to concretely address L&D. In order to be a full mechanism, the WIM needs to define clear and precise strategies and actions plans for implementing its functions concretely. In particular, one of its first steps must be establishing a separate financial arm with the relative indications in terms of contribution’s responsibility. In fact, the WIM’s mandate requires that methods to remedy losses - including recovery and rehabilitation - are established. Clear information on the source of L&D finance, on the modalities of the financial access and on the estimates of L&D costs in the most vulnerable countries need to be urgently provided.

Of course, nothing of all this will be possible without a change of direction of the actions carried out by the developed countries. The latter cannot continue to avoid the financial topic and to implement obstructive measures during the international climate negotiations. It is time they assume their responsibilities towards the internationally shared objectives of the WIM. Especially considering that, even those states that have been always afraid to criticize the UNFCCC process because they staked their future in climate change negotiations, have decided to entrust their future to other systems for trying to achieve more concrete outcomes.

To conclude, there is still a lot to do to effectively support with concrete and tangible actions those countries that are daily suffering climate change L&D. Unfortunately, the outcomes of the 25th COP held in Madrid last December were not positive for the L&D debate. However, regardless of its results, I think it is a turning point for the L&D discourse. Developing countries have already started pursuing new avenues for addressing L&D giving the developed countries a clear message that they will face any kind of blockade.