When Career Guidance Becomes Marketing: Risks and Alternatives for Supporting Young People

The article published by the local newspaper Il Mattino di Padova, describing the pilot project “Scopri il talento per l’orientamento” (Discover Your Talent for Career Guidance), under the title “A Pilot Project for School Guidance” and promoted by ESU Padova in collaboration with the private company Gate Italy, has raised several concerns for the present author. These concerns arise not only from the reductive communication approach, which presents career guidance as a mere test to be administered to students aged 17–19 but also from the implicit message conveyed: namely, that guidance is an ancillary and predictive procedure, which anyone can implement regardless of any genuine scientific background in the field.

The author has worked in the field of guidance for many years—an area of study and professional practice recognised internationally—and observes with growing concern the simplistic tendencies with which this domain is treated. Reducing career guidance to a “test to find the right university faculty” undermines its scientific, ethical, educational, and social value. It means forgetting that in Italy there are long-established institutions such as the Italian Society for Vocational Guidance (SIO), which brings together scholars and practitioners, and that the University of Padua itself hosts centres of excellence in research and training on this topic, as demonstrated by educational programmes led by Professor Laura Nota, projects developed by the La.R.I.O.S. Laboratory, and a range of postgraduate training programmes, research fellowships, and doctoral projects dedicated to this discipline.

Therefore, one might question how it is justifiable that a guidance project is being promoted by ESU—a regional body for the right to education, institutionally autonomous from but functionally linked to the University of Padua—in partnership with actors outside the academic domain of guidance, whose scientific production in the field is neither documented nor recognised according to the standards of the reference community. One wonders how this can occur while the same university signs agreements with public bodies and invests resources in the training of experts capable of supporting complex decision-making processes through evidence-based practices. Why not start by involving the neighbouring institutions, with their established expertise?

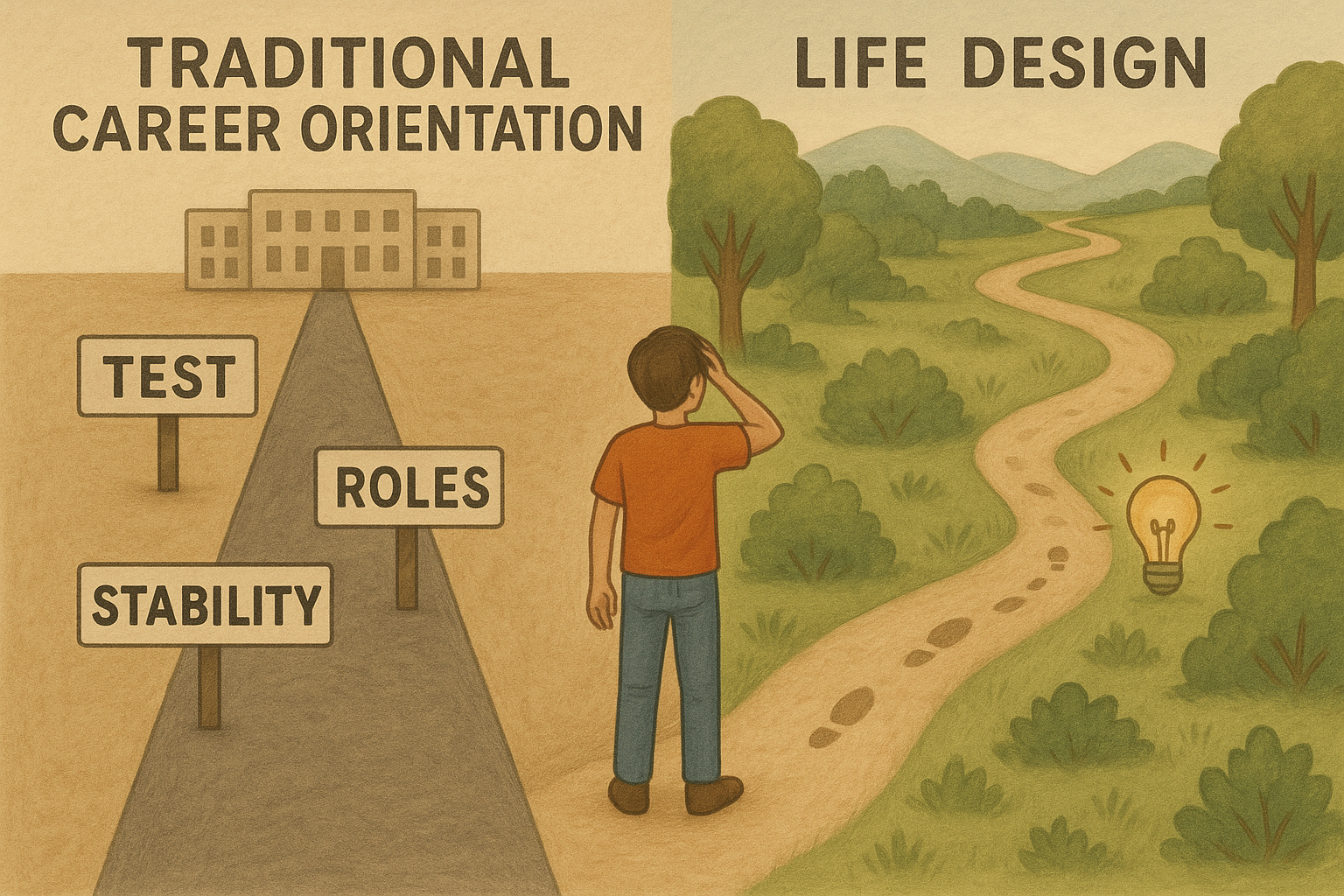

The project "Discover Your Talent for Career Guidance," as described on its official website and in a PDF presentation, makes explicit reference to the use of psychological tests and statistical analyses, particularly about multiple intelligences, self-efficacy, and mental imagery. In the form of standardised testing, this approach is presented as a scientific tool to guide students in choosing their university or professional path. However, reducing guidance to a test measuring “talent matrices” and “vocational preferences” amounts, as Salvatore Soresi (2023, 2024) has already pointed out, to stripping guidance of its educational, transformative, and critical dimensions. The model proposed reflects a predictive and prescriptive view of guidance, which is opposed to the Life Design perspective, focusing instead on meaning-making, openness to possible futures, and promoting hope and critical thinking. In this regard, reference must be made to the foundational work of Savickas and colleagues (2009) on career construction and Life Design, which promotes a guidance approach based on narrative action, identity as a process, and the capacity of individuals to shape their lives even in unstable contexts. This vision has been developed further by many international scholars, including Laura Nota (University of Padua), José Duarte (University of Lisbon), Jean Guichard (CNAM–Paris), Salvatore Soresi (University of Padua), Mark Savickas (Northeast Ohio Medical University), Erik Salvatore Rossier (University of Lausanne), and Raoul Van Esbroeck (Vrije Universiteit Brussel). These researchers, actively involved in the international research group that has for years been advancing the theoretical and conceptual framework of Life Design, work in synergy with academic and professional networks such as the European Society for Vocational Designing and Career Counselling (ESVDC), the Society of Vocational Psychology (SVP), and the National Career Development Association (NCDA).

In support of this perspective, the international conference Career Guidance and Counselling for Hope in the Anthropocene was recently held in Joensuu, Finland (March 2025), organised under the UNESCO UNITWIN Chair on Lifelong Guidance and Counselling, with the direct involvement of academics from the University of Padua who are active in the guidance field (none affiliated with Gate Italy). The event gathered experts from around the world to reflect on the role of guidance in times of ecological, social, and economic crisis. The keynote lectures by Meenakshi Chhabra, David Blustein, and Antti Rajala, as well as a video address by Jean Guichard, reaffirmed that guidance must be an ethical, relational, utopian, and sustainable practice—capable of cultivating hope and dignity. Far from any deterministic or market-oriented view, guidance was conceived as a space for critical reflection and the co-construction of desirable and shared futures. The workshops and parallel sessions highlighted the importance of narrative, participatory, and situated approaches, confirming the need for guidance practices grounded in awareness and social justice.

The materials presented by the Padua-based project never specify which psychometric tools were used. Statements regarding the test’s “scientific validation” are vague and unsubstantiated. Although reference is made to multiple intelligences, Howard Gardner himself has consistently emphasised that his theory was never intended to be used as a diagnostic tool. The lack of references to reliability, validity, and standardisation requirements suggests an instrumental and potentially misleading use of psychological assessments. The underlying message is that each student can “discover their talent” and make the “right choice” simply by taking a test. This dangerously resembles a meritocratic and individualistic view, entirely neglecting sociocultural contexts, structural inequalities, and environmental influences—central elements in both Life Design theory and Blustein’s (2009) psychology of decent work.

It is paradoxical that despite the University of Padua being among the institutions that have most invested in the scientific training of career guidance professionals, interdisciplinary research, and international networks (SIO, ESVDC, NCDA, SVP), a nearby institutional initiative promotes guidance through non-specialist actors and a pedagogically oversimplified framework. Even if not directly attributable to the University itself, the institutional proximity and the failure to involve its experts render the choice at the very least questionable. Perhaps, as Soresi provocatively suggests (2024), we should reflect on the risk that even contexts culturally close to the university may—albeit unintentionally—contribute to the production of agnotology: that is, a form of manufactured ignorance, which can spread even within academic settings when well-established theoretical and scientific frameworks are ignored in favour of simplified, market-driven approaches. The casual and unfounded use of terms like “talent”, “achievement”, “soft skills”, or “personalised training” contributes to semantic erosion, obscuring the complexity of guidance knowledge through an appealing yet epistemologically superficial language.

In the materials published by Gate Italy, one finds no reference whatsoever to key concepts such as future, sustainability, hope, participation, citizenship, social justice, planning, or collective aspirations—all of which represent the most advanced and internationally shared conceptual pillars of contemporary guidance (Nota & Soresi, 2020; Pitzalis & Nota, 2024).

The project “Discover Your Talent" presents itself as an innovative solution but, in light of the reflections of Soresi, Nota, Savickas, Guichard and other Life Design authors, it represents a step backwards. It is not even entirely new if we consider that around twenty years ago the University of Padua had already promoted an innovative guidance system known as Magellano, developed in collaboration with Giunti OS and still available on the publisher’s website. Unlike what is happening today, that project was coordinated by experienced scholars and practitioners, received the patronage of the President of the Republic, and involved the use of scientifically validated psychometric tools, designed to support thoughtful reflection on the future. It was built on a rigorous conceptual framework and a personalised, participatory approach aimed at supporting young people in complex decision-making processes with careful attention to dignity, future plurality, and conscious planning. By comparison, the current proposal appears to lack scientific foundation, sensitivity to context, and conceptual depth. It promotes a test-based, impersonal model of career guidance, rooted in individualising logic, which risks trivialising a complex and vital discipline.

Genuine guidance does not simply discover talent—it accompanies it, contextualises it, and nurtures its growth about others and the world. Career guidance is not a test: it is an educational, ethical, and transformative practice. And it must be treated as such.

References

Blustein, D. L. (2019). The importance of work in an age of uncertainty: The eroding work experience in America. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190213701.001.0001

Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice. Basic Books.

Nota, L., & Soresi, S. (2020). Sustainable Development, Career Counseling and Career Education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60046-4

Pitzalis, M., & Nota, L. (2024). L’orientamento a scuola. Per costruire società inclusive, eque, sostenibili. Mondadori Education.

Savickas, M. L., et al. (2009). Life designing: A paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(3), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-6676.2012.00002.x

Soresi, S. (2023). A proposito delle innovazioni introdotte nelle nuove linee guida per l’orientamento. Nuova Secondaria, 7, 70–177.

Soresi, S. (2024). C’è più orientamento al futuro nelle ‘nuove linee guida ministeriali’ o in ChatGPT? Roars, 13 giugno.