A Spiral within the Spiral: Indigenous Peoples right to healthcare in Brazil during COVID-19

Table of Contents

Multi-Level Governance and Human Rights

Brazil, as a federal state, has a unique governance structure that distributes power across the federal, state, and municipal levels. Federalism is a form of multi-level governance where power is shared across different levels to prevent it from being concentrated in a single one. This approach allows communities to work together on shared interests, goals, and values while respecting certain differences. It also makes some duties of the State more manageable, as local authorities have a closer connection to the population and its needs. However, dividing power among multiple actors can add complexity to policymaking and may increase regional inequalities. In Brazil, for example, Indigenous affairs are mainly concentrated at the federal level, but state and local governments also contribute to policy development and implementation.

Brazil’s COVID-19 pandemic response highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of its multi-level governance model. Multi-level governance, particularly within human rights frameworks, often requires contributions from various actors. The main argument of this article is that there is a "spiral within the spiral." This perspective suggests that, beyond the broad national and international forces impacting state behavior (as described by the Spiral Model of Human Rights Change), there are also layers of interaction and pressure within the country itself. These involve different levels of government – federal, state, and municipal – and civil society groups. In Brazil, these internal dynamics form a secondary spiral, where state and local governments, along with civil society organizations, put pressure on the federal government and on each other to uphold human rights commitments.

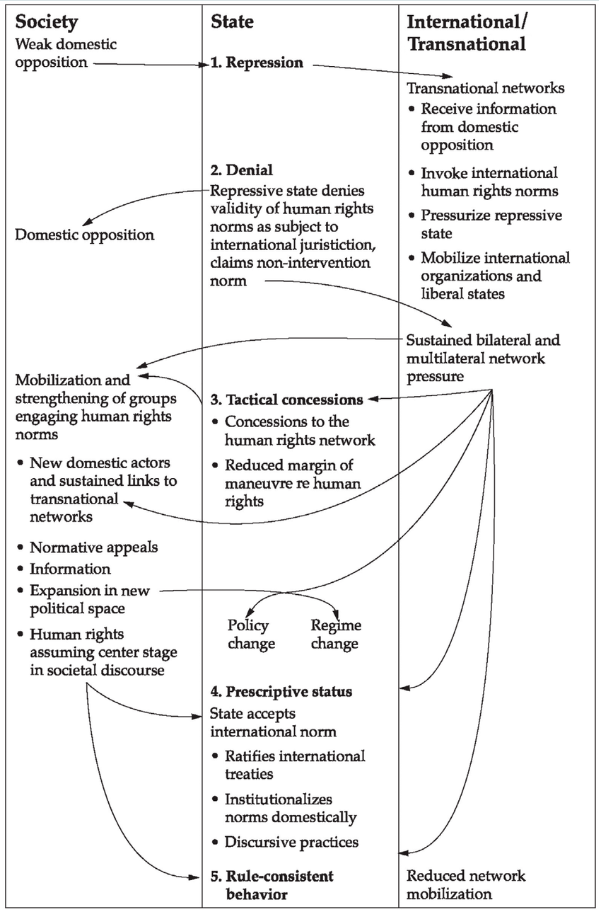

The Spiral Model of Human Rights Change

The Spiral Model of Human Rights Change, proposed by Thomas Risse and Kathryn Sikkink, suggests that states internalize international norms through a series of phases: The spiral model consists of five phases. The first phase, State Repression, occurs when government policies violate human rights, prompting political opposition with local civil society organizations beginning to mobilize in response of the violations. They engage international networks, with other organizations to build broader support, aiming to build external pressure from other states. In the second phase, Denial, the government tries to disprove these allegations of human rights violations, indicating that the pressure is beginning to have an effect. In the third phase, Tactical Concessions, the government makes small concessions to alleviate this pressure, allowing local organizations to shift their focus from seeking international support to addressing domestic issues directly. The fourth phase, Prescriptive Status, marks a significant turning point as the government starts participating in international treaties and amends domestic legislation to align with human rights standards. In the final phase, Rule-Consistent Behavior, the government consistently upholds international human rights law, and respect for human rights becomes a shared societal value and an expected norm.

In Brazil, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing tensions in human rights governance. The federal government’s neglect of Indigenous healthcare during this period illustrated the spiral model in practice. When the federal level failed to meet Indigenous healthcare needs, local governments and CSOs sought to protect these communities, often providing healthcare resources and advocating for rights.

Indigenous Peoples in Brazil: Historical and Current Challenges

Brazil’s Indigenous peoples have long endured marginalization and inadequate protections, dating back to the arrival of the Portuguese and the many years of colonization and, more recently, to the military dictatorship period (1964–1985). The 1988 Brazilian Constitution was a landmark for Indigenous rights, recognizing their right to land, culture, and specific protections. During the Constitutional Assembly, Indigenous organizations prioritized advocating for Indigenous issues to be placed under federal jurisdiction. Historically, local authorities have often undermined Indigenous rights, as municipalities and states are where landowners and land grabbers hold the most influence and are more likely to exert power against Indigenous communities.

The 1988 Constitution also created the Unified Healthcare System (SUS). As the world’s largest entirely free healthcare system, SUS guarantees healthcare access to all individuals within Brazil’s borders, including foreigners. In 1992, the 9th National Health Conference focused on decentralizing and municipalizing primary healthcare services. The Indigenous movement, however, opposed the municipalization of healthcare, fearing it would undermine their rights. They advocated for federal responsibility in Indigenous health, culminating in the establishment of the Indigenous Health Subsystem through Special Indigenous Health Districts (DSEIs), with federal oversight. This structure was formalized in 1999 by the “Arouca Law”. There are currently 34 Special Indigenous Health Districts in Brazil.

The 2002 election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva initially raised hopes among Indigenous communities due to his Workers Party’s historical support. However, Lula’s administration (2003 – 2010) faced challenges in fully guaranteeing Indigenous rights due to political compromises with powerful agribusiness interests. In response to these challenges, his term saw the formation of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) in 2005, which became the leading national Indigenous organization. APIB is an umbrella organization for regional Indigenous organizations, which also serve as an umbrella for local organizations and leaders

Dilma Rousseff's 2010 presidential victory kept the Workers Party (PT) in power, but her administration faced significant challenges with Indigenous groups. Despite being re-elected in 2014, Rousseff's presidency ended prematurely with her 2016 impeachment, leading to Michel Temer’s brief presidency (2016 – 2018), marked by agribusiness-aligned policies that intensified struggles for Indigenous communities. After Rousseff’s government, PT and Indigenous groups grew distant, but PT reconnected with the Indigenous movement during Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency (2019 – 2022). In the lead-up to the 2022 election, Lula da Silva ran on a platform promising the creation of a Ministry of Indigenous People.

Brazil’s Federal Government Response during COVID-19

Jair Bolsonaro took office as president in 2019 and had an open policy of attacking the environment and the Indigenous Peoples that started before his presidential campaign and continued in his first year in office. The right to land continued to be a major obstacle for Indigenous people as Bolsonaro halted the recognition of Indigenous lands, but the COVID-19 pandemic, that began in his second year in office, exposed his absolute disregard for human rights, the rule of law and science.

Bolsonaro tried to centralize all pandemic decision-making within the federal government. However, the measure faced opposition and was challenged in Brazil’s Supreme Court. The Court ruled that all levels of government (federal, state, and municipal) have the authority to legislate and make decisions related to public health, including COVID-19. This affirmed the concurrent powers of states and municipalities to address public health emergencies based on local needs.

The federal government under Jair Bolsonaro also did not follow scientific recommendations and hindered efforts to protect vulnerable populations, particularly Indigenous Peoples, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bolsonaro's administration did not consider urban Indigenous communities part of its healthcare obligations, leaving them disproportionately affected by the virus. Due to these persistent failures, the Indigenous organization APIB took the unprecedented step of petitioning the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the Indigenous Peoples. However, despite this legal victory, the government’s approach remained unchanged. In response, APIB filed a complaint against Bolsonaro at the International Criminal Court in August 2021, accusing him of crimes against humanity and genocide.

Several Supreme Court rulings pressured the federal government to take responsibility for Indigenous healthcare during the pandemic, underscoring the legal obligation to provide equitable healthcare access. However, the federal government largely failed to respond adequately, often focusing efforts elsewhere or resisting interventions from the judiciary. Consequently, a healthcare vacuum emerged, which was filled to some extent by state and municipal governments and CSOs.

Roles of State and Municipal Governments and Civil Society Organizations

Amidst the federal government’s inadequate response, state and municipal authorities and CSOs filled crucial gaps in Indigenous healthcare. Local governments took varied approaches based on regional needs and available resources. For example:

- State Contingency Plans: States across Brazil developed their own contingency plans tailored to Indigenous healthcare needs. While these plans varied in effectiveness and scope, they represented an important localized approach to health governance, attempting to bypass federal inaction. The thesis analyzed all the plans from the 26 Brazilian states and the Federal District.

- Municipal Involvement: In regions with high Indigenous populations, municipal governments coordinated with healthcare providers to ensure COVID-19 testing, vaccinations, and primary care.

- Civil Society Organizations: CSOs and Indigenous rights groups became essential healthcare providers. Organizations such as APIB played a pivotal role, organizing campaigns for healthcare funding, providing medical supplies, and advocating for stronger government interventions.

This grassroots response demonstrated a “spiral within the spiral” effect, where local actors and civil society advocated for healthcare rights independently of federal mandates, often putting pressure on state and municipal governments to act as intermediaries.

In essence, a spiral within a spiral was identified. This involved three levels and other branches of government, as well as local and national organizations. Assistance was also provided by international organizations. Initially, Bolsonaro denied the virus's severity, centralized decision-making, and undermined Indigenous rights, prioritizing economic over health policies. Civil society groups, NGOs, and the Supreme Court pushed back, leading to decentralization, allowing states and municipalities to implement their own prevention measures, according to their contingency plans. The government’s neglect was further exposed when Bolsonaro fired two health ministers and promoted ineffective treatments like chloroquine.

CSOs started working with other governments offices and putting pressure on governors and mayors. For example, in the state of Goiás, the governor, after meeting indigenous leaders, proposed a law dedicated to providing care for Indigenous Peoples; in the city of São Paulo, the combined efforts of the Public Prosecutors office with Indigenous organizations and municipal authorities ensured this population could access city healthcare institutions; in Mato Grosso do Sul, the state government and Indigenous organizations worked together and called Doctors Without Borders to help expand the healthcare system, despite resistance from the federal government; in the city of Maricá, city officials came together with local Indigenous organizations to create sanitary barriers and provide dedicated care; the state of Acre created a working group with Indigenous participation after those managed to get support from the World Health Organization to their needs.

These state and city governments went outside of their legal competencies to ensure at least some protection for this population. While these are some more visible and clear examples of actions, some movements happened across the entire country, with state governments assuming the role of primary data collectors on cases and deaths among Indigenous communities , ensuring at least some transparency in the numbers available. What we saw was a spiral where the networks of Indigenous organizations with other CSOs, different levels and branches of power, with the pressure of the international community, have managed to ensure the enjoyment of rights. In any way, all of this means that Indigenous Peoples were protected from inhumane treatment, lack of care, and possibly genocide.

This mobilization led to systemic opposition, culminating in the 2022 elections when then opposition parties gained power. Sônia Guajajara, an Indigenous leader, now heads the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, marking a significant victory for Indigenous rights.

Findings and Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the complexities of protecting Indigenous rights within Brazil’s multi-level governance structure. The thesis’s findings suggest that local governments and CSOs can sometimes compensate for federal negligence, providing healthcare and other resources where the national government has fallen short. However, these efforts are not a substitute for federal action, and without centralized coordination, there are risks of inconsistent protections across regions.

Furthermore, the thesis emphasizes the importance of including civil society in multi-level governance, particularly in human rights advocacy. CSOs provided essential services and resources during the pandemic, but they also helped increase public awareness and policy accountability. Their involvement offers valuable insights into how governance structures might be reformed to include Indigenous voices and community needs in policy-making processes.

In summary, the “spiral within the spiral” concept demonstrates that, even under repressive or neglectful federal administrations, local governments and civil society actors can initiate meaningful changes in human rights protections. It proves that while the original Spiral Model explains human rights change at a broader international level, there is also a spiral inside other domestic levels of governance. To conclude, the thesis did not intend to speak on behalf of the Indigenous Peoples; on the contrary, it shows that they can speak for themselves. The intention was to learn more about the strategy Indigenous leaders have developed and implemented, place it within a theory, and expand it.