Council of the European Union: new research paper “One Roof, Many Realities” points to the strategic importance of housing rights in contemporary Europe

Table of Contents

- Introduzione

- L'aumento del costo degli alloggi in Europa

- Carenza di offerta e calo dell'edilizia

- Invecchiamento, urbanizzazione e nuove esigenze abitative

- Finanziarizzazione e riorganizzazione dei mercati immobiliari

- L'importanza degli alloggi per la competitività e la democrazia

- Sfide politiche per l'UE

- Conclusione

Introduction

The housing crisis across Europe is no longer a localised problem but a structural and interconnected challenge affecting nearly all Member States. Although each country and even each region faces different pressures, the crisis shares a common European dimension. Rising prices, growing demand, demographic shifts, energy inefficiency and increasing financialisation converge to reshape living conditions for millions.

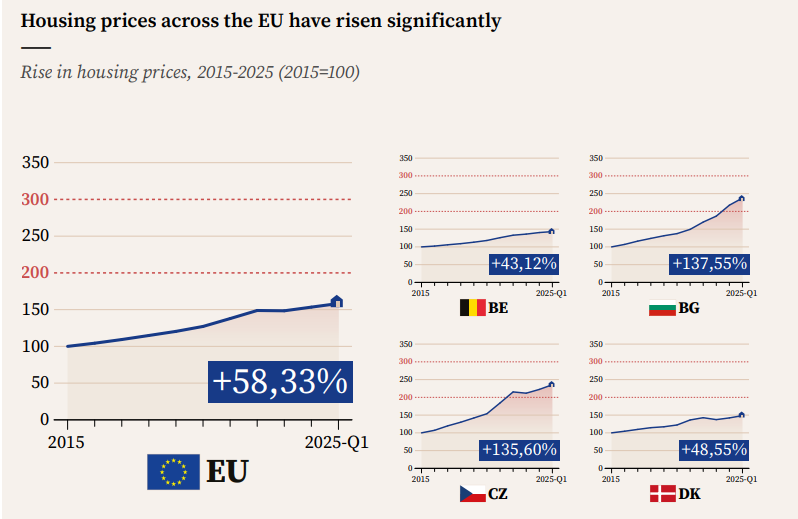

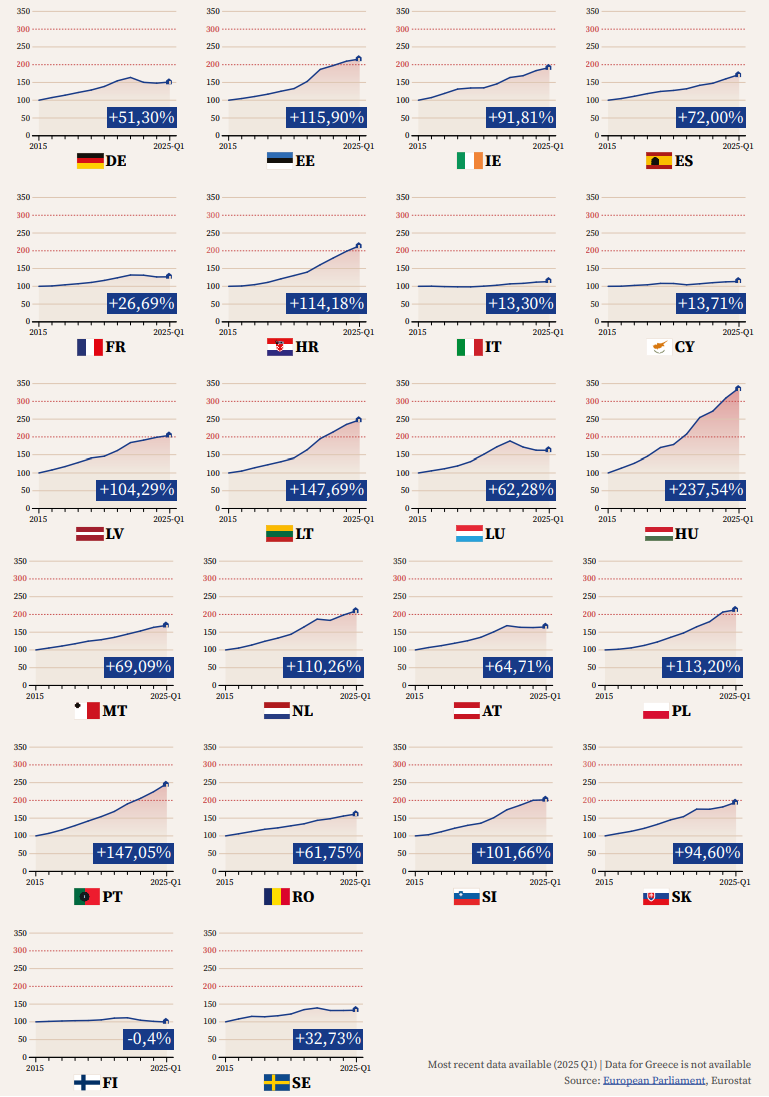

According to the European Council's Analysis and Research Team, housing prices in the EU rose by almost 60% between 2015 and 2025, faster than wages, further widening the gap between incomes and housing costs.

Urban areas have been particularly affected, with demand rising far faster than supply.

The Rising Cost of Housing in Europe

Across Europe, affordability has deteriorated sharply. Housing costs, including rent, mortgage payments, and utilities, consume an increasingly large share of household budgets. In 2024, one in ten EU households struggled to pay rent or a mortgage on time, and 15% fell behind on utility bills. Additional data from the Council report shows that EU households spent an average of 19.2% of their disposable income on housing in 2024. The burden is heavier in cities: 9.8% of urban residents spent over 40% of their income on housing, compared to 6.3% in rural areas. This highlights a clear urban–rural divide in affordability.

The most striking trend is the rapid escalation of property prices. In Member States such as Hungary (+237%), Estonia (+115%), Latvia (+104%) and Portugal (+147%), house prices more than doubled between 2015 and 2025. Italy is among the countries where costs have risen less, with a 13% increase over 10 years.

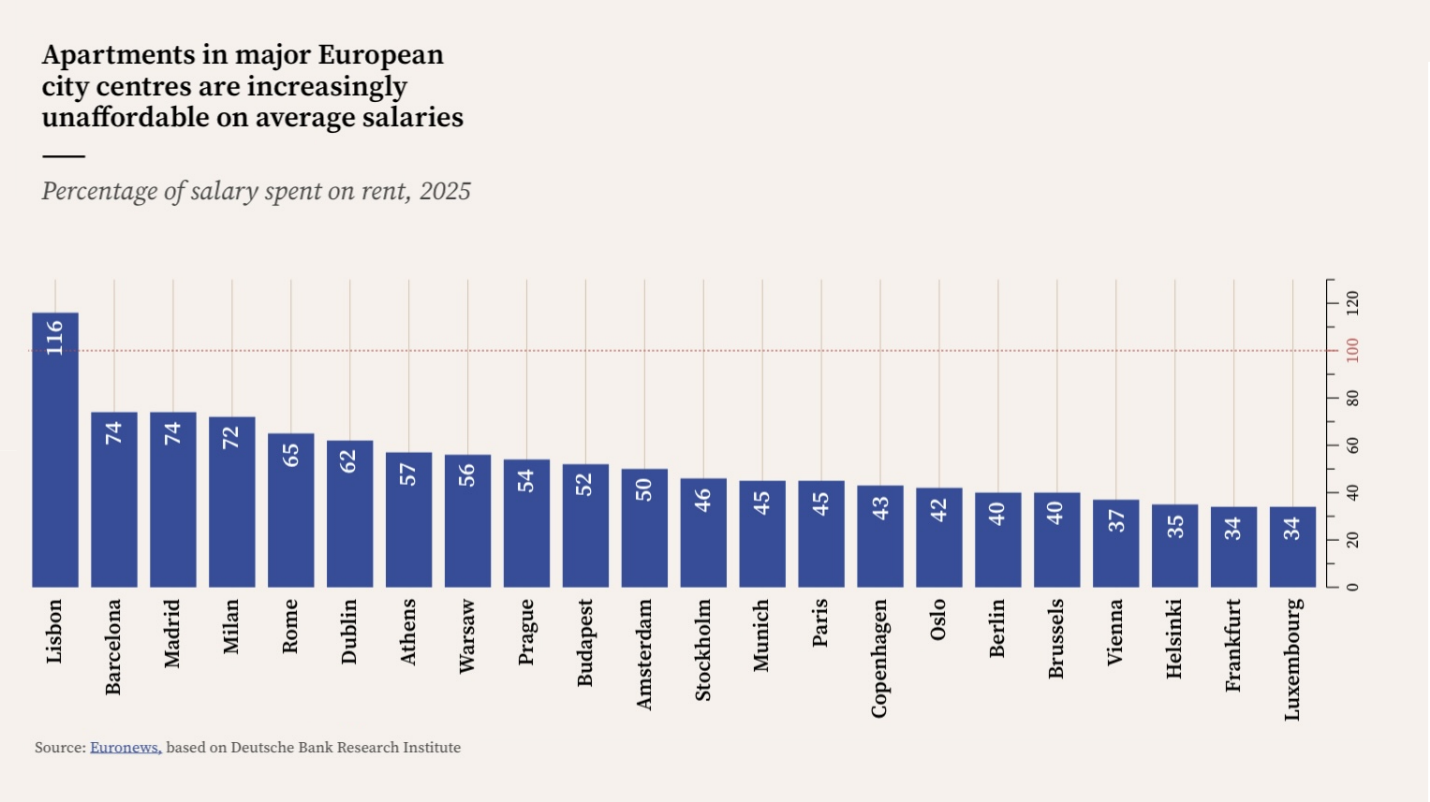

EU rental prices increased by almost 29% between 2010 and 2025, with capital cities such as Lisbon, Dublin and Stockholm experiencing even sharper increases. In Rome, in 2025, 65% of an average salary was spent on rent, 72% in Milan. Young people are disproportionately affected; in 2024, the average age at which Europeans left their parental home reached 30 or more, in Slovakia, Greece, Croatia, Italy, and Spain.

Beyond income constraints, energy costs also play a major role. With 75% of EU buildings classified as energy-inefficient, households face high heating expenses, particularly in older buildings. The research shows that 85% of residential buildings were built before 2000, and only around 1% undergo energy-related renovation each year. Deep renovations that improve energy efficiency by at least 60% are extremely rare, representing just 0.2% of buildings annually. These structural limits make it difficult to reduce housing costs for low-income households.

Supply Shortages and the Decline of Construction

Europe is not building enough. Despite the estimated need for one million additional homes, construction has slowed considerably. The root problem is the rising cost of construction materials and labour. EU construction costs rose 56% between 2010 and 2024, with dramatic increases in Hungary (159%), Bulgaria (136%) and Romania (116%). Also, in this case, Italy proves to be less dynamic, with a 24% increase.

Three major disruptions have shaped this decline: The 2008 financial crisis, which reduced long-term investment in new housing, the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted supply chains and labour availability, and the energy crisis after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, which drove up costs further.

Ageing, Urbanisation and New Housing Needs

Demographic and societal shifts are accelerating pressure on the housing market. Europe is becoming increasingly urban. Urbanisation is expected to reach 83% by 2050, largely driven by the ongoing economic pull of major cities. This expansion deepens regional inequality: while urban centres gain population, rural regions lost 8 million inhabitants between 2014 and 2024. At the same time, the number of people aged 65 or older continues to grow faster in rural areas, increasing by 1.5–1.7% annually.

These changes affect housing needs in several ways:

- Smaller households: one- and two-person households are becoming dominant as birth rates fall and populations age.

- Under-occupied homes: one-third of Europeans live in homes larger than they need, mainly elderly residents who cannot afford to downsize.

- Increasing demand for affordable units: the European Commission estimates a shortage of 4 million affordable homes across the EU.

- Rural ageing: areas facing depopulation must adapt services, infrastructure and housing to older residents.

At the same time, student housing shortages have become critical in countries such as Ireland, France and the Netherlands, limiting mobility and access to education.

Financialisation and the Reshaping of Housing Markets

One of the most significant yet often overlooked drivers of the crisis is financialization, the transformation of housing into a financial asset. Institutional investors like private equity firms, real-estate funds and pension funds now own large segments of the housing market.

Research shows that institutional investors typically raise rents more quickly than other landlords, invest less in renovations, prioritise high-end developments over affordable housing, and extract local wealth without reinvesting it back into communities.

Financialisation also drives the proliferation of short-term rentals, such as Airbnb. In 2024, EU short-term rentals generated 152.2 million overnight stays, reducing long-term rental availability in key destinations.

Housing Matters for Competitiveness and Democracy

Housing is a fundamental economic issue. High housing costs reduce disposable income and local consumption. More importantly, they disrupt labour markets: skilled workers decline opportunities in high-cost regions, limiting productivity and innovation, while students face severe obstacles in relocating for education.

The housing crisis increases inequality: 63% of EU household wealth is tied to homeownership, meaning renters fall further behind as prices rise. Multiple studies show that rising rents correlate with increased support for far-right populist parties, which frame housing scarcity as a migration issue. Even stagnating rural house prices produce polarisation, as rural homeowners feel left out of urban wealth gains and often vote against incumbent parties. In short, housing is now a major factor in Europe’s political divides.

Policy Challenges for the EU

Although housing remains largely a national competence, EU-level discussions increasingly focus on the crisis because of its cross-border implications. One major challenge lies in the wide diversity of housing systems across Member States. Some countries rely heavily on homeownership without mortgages, such as Romania and Bulgaria, while others, including Germany and Spain, are characterised by large market-rental sectors. In Northern Europe, countries like Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands maintain strong social housing systems. This structural diversity makes it difficult to design one-size-fits-all solutions at the EU level.

At the European level, housing is addressed through Article 34(3) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, which recognises the right to social and housing assistance for individuals who lack sufficient resources, in order to ensure a decent existence, in accordance with EU law and national laws and practices. In addition, Article 31 of the European Social Charter recognises the right to housing by committing States Parties to promote access to adequate housing, prevent and reduce homelessness, and ensure housing affordability for persons without adequate resources.

Italy’s housing context is marked by long-term market stagnation, moderate construction dynamics, and persistent demographic challenges. Italy was the only EU Member State to record an overall decline in house prices between 2010 and 2025 (–1%), in contrast to an EU-wide increase of over 60% during the same period. Although housing prices rose by 13.3% between 2015 and early 2025, this growth remained relatively limited. Construction costs increased by only 24% between 2010 and 2024, well below the EU average, reflecting weaker market dynamism and constrained investment in new housing supply. These market trends intersect with demographic patterns, including delayed residential independence, as young people in Italy left the parental home at an average age of 30 years old in 2024. At the same time, internal migration continues to concentrate population in urban centres, while inner areas experience ongoing depopulation, a challenge acknowledged in Italy’s 2021–2027 National Strategy for Inner Areas. Within this context, Italy’s housing system remains structurally rigid, characterised by a dominance of owner-occupation without mortgages and a limited rental sector, reducing housing flexibility for younger and more mobile groups.

A second challenge concerns political support for certain policy measures. Homeowners generally oppose redistributive housing policies, such as rent controls, higher taxes or the expansion of social housing.

Finally, different policy tools involve significant trade-offs. Rent controls can make housing more affordable, but may reduce residential mobility and discourage maintenance. Subsidies can help at-risk households but may inflate prices if supply remains limited. Energy-efficiency renovations reduce long-term utility costs but require substantial upfront investments. Increasing private investment can expand supply, but risks deepening the financialisation of the housing market.

Conclusion

Europe’s housing crisis is multidimensional. It reflects long-term structural issues, demographic change, rising energy costs, financialisation and inequalities between regions. While Member States hold primary responsibility, the EU has a crucial role to play in promoting better data, encouraging sustainable renovation, supporting innovation in construction, addressing financial market risks and facilitating knowledge exchange.

Housing is not only a social concern. It is also central to Europe’s competitiveness, social cohesion and democratic stability. The debate at the EU level signals recognition that ensuring access to adequate, affordable and sustainable housing is essential for the future of the Union. Strengthening cooperation between national governments, local authorities, and European institutions will be fundamental to translating these discussions into effective, coordinated policy action. Moreover, addressing the housing crisis requires not only technical solutions but also a long-term vision that balances economic, environmental and social priorities. Ultimately,the EU research paper calls for a more equitable and resilient housing system, essential to safeguarding public trust and supporting the EU’s broader goals of prosperity and cohesion.