Fostering Democratic Resilience: The Role of Internationalized Constitutional Adjudication in Africa

Table of Contents

1. Internationalization of African Constitutionalism

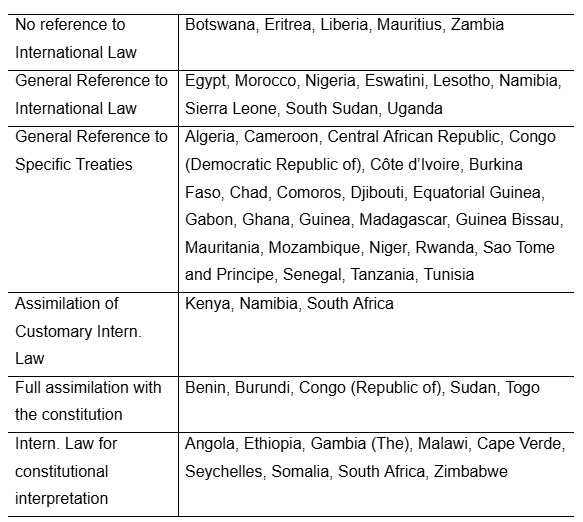

By definition, constitutional law pertains to the domain of the state. It is the supreme law of the land, bound to regulate and balance powers within a well-defined territory. It might then seem counterintuitive to theorize a model of constitutional behaviour that implies features of internationalization. And yet, a growing number of scholars have tried to define and understand what is today considered an inevitable trend of constitutional law. To some, the causes behind said constitutional evolution are to be found mainly in globalization and the mainstreaming of the human rights discourse. Irrespective of the underlying motives, two main aspects of constitutional internationalization have been observed: on the one hand the (more or less) integral incorporation of international human rights treaties in domestic constitutions, resulting in national charters becoming progressively alike; on the other, constitutional judges increasingly making reference to foreign judicial decisions for constitutional interpretation. The African continent makes no exception to these constitutional and judicial tendencies. Regarding the incorporation of international law provisions, the table below tries to classify different gradients of assimilation.

Noteworthily, the majority of African constitutions share some degree of international integration. On top of that, international judicial dialogue – often referred to as “judicial cross fertilization”– can also be easily observed when it comes to African constitutional adjudication. A brief analysis of the continent’s most prominent judicial decisions evidently shows a substantial and significant use of foreign and international elements for the interpretation of domestic legislations. Looking at African case law, many examples of the sort can be made. To name a few, South Africa’s supreme court decision State v. Makwanyane (on capital punishment) contains an astonishing number of 220 references to foreign law. Zimbabwe’s State v. Chokuramba (on the legality of corporal punishment on minors) mentions constitutional courts from Namibia, South Africa and the US, besides a series of international courts’ decisions. Adding to the point, a study shows that 93% of Namibia’s supreme court rulings use foreign law to formulate an opinion. To put it briefly, the use of foreign judicial decisions as authoritative sources of law for constitutional adjudication can be observed throughout the continent. This shows that Africa bears no exception to developments of constitutional internationalization.

2. Democracy and Constitutional Retrogression

How does a more international approach to constitutional adjudication affect a state’s form of government? More specifically, does cross-judicial dialogue influence democratic institutions, by ultimately strengthening their overall resilience? To better understand these questions and their possible outcomes, one must first consider the delicate nature of pluralistic societies. Democracies are not a given fact, they are a product of centuries of political and social evolution. Never before has the world seen so many democratic constitutions. But progress is not irreversible. Setbacks may well occur: rights can be retracted, checks and balances distorted, minorities oppressed. Democratic decay is the name that has been given to said processes of pluralistic regression. Democracies may falter in front of an abrupt and violent change of power, but they can also experience more subtle and covert ways in which their very essence is put in jeopardy. The latter phenomenon, that often follows the paths of constitutional legitimacy, has been called “constitutional retrogression”. The executive might retain too much power, they might weaken the judiciary, maiming individual rights, segregating oppressed groups. These processes are gradual, but they ultimately deteriorate democracies, undermining their core principles with a piecemeal approach. As the main guardians of democratic values, can constitutional judges halt these undemocratic impulses, by referring to foreign judicial decisions for constitutional interpretation?

3. A comparative study on Judicial Cross-fertilization

In order to give an answer to the question, one shall look at African case law in a comparative perspective. For the sake of the present analysis, a list of judicial decisions that tackled specific legislations was taken into consideration. Had these regulations passed, they would have weakened some core democratic assumptions: the protection of individual or groups’ rights, a balanced division of state’s powers, the regularity and fairness of general elections.

With regard to electoral outcomes, Kenya’s 2017 presidential election offers a significant example of judicial intervention. Accusation of general unfairness by political opposition led the case for an unlawful counting of the ballots up to the Supreme Court (Raila Amolo Odinga v. IEBC and others). The judgement had a considerable impact since it ultimately nullified the results, calling for a new vote. Hence, the constitutional judges found some irregularities in the process, and acted to stop its distorted results. Interestingly enough, they do so by making substantial use of comparable foreign decisions. This does not mean that the Court adopts foreign sources as an additional or incidental element to their argument; it rather means that it builds the whole ruling on external judgements. Just to give a general overview, the ruling is based on jurisprudence from the United States, Botswana, Uganda, Nigeria, Ghana, India, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, South Africa, Mauritius, Tanzania, Seychelles and Australia. It is indeed an unmistakable example of how the internationalization of judicial interpretation can be an additional instrument in the hands of the judges in order to defend some democratic features.

As anticipated, another essential democratic attribute lies in the separation of powers within the state. On this matter, Zimbabwe’s Supreme Court ruling on the case Kika v. Minister of Justice Legal and Parliamentary affairs and 19 others is exemplary. The decision examined some constitutional amendments which concentrated more power in the hands of the president, such as the ability to extend the term of constitutional justices. Most notably, the Court draws the entire ruling by taking inspiration from neighbouring Sout Africa’s case law. Indeed, upon deciding that amending the judiciary must in no way favour the incumbent, Zimbabwe’s judges make no use of domestic precedents, relying almost entirely on South African constitutional cases. It is safe to assume that, had the judges disdained a more open approach to international influence, the final decision would have been reasonably different both in structure and outcome.

Threats to the democratic order may also come from attempts of the executive to curtail individual and groups’ rights. South Africa’s Mlungwana and Others v. S. and Another can serve as an example of judicial intervention, arresting these freedom-restricting drives. The case concerned a legislation that criminalized public gatherings that weren’t able to notify the local municipality, for security reasons. The Court, finding the piece of law unconstitutional, makes extensive use of international courts’ decisions on the matter. The South African judges refer to the UN Human Rights Committee, the European Court of Human Rights and the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights, developing their argument entirely from foreign jurisprudence. Many examples of the sort can be made, with courts throughout the continent defending rights in the light of external interpretations. At times, foreign references might also be effective in recognizing rights not originally included in national constitutions. This is the case of Uganda’s UOBU v. Attorney General, acknowledging land rights of indigenous people in consideration of foreign case law (from, among others, the UK, Australia, Canada, South Africa, Botswana and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights).

The above rulings are just a small sample, illustrating the systemic use of foreign opinions as authoritative sources of law for constitutional interpretation in Africa, in cases where the legislations under scrutiny would have weakened democracy and threatened the integrity of pluralistic societies.

4. Conclusions

There seems to be a correlation between the use of foreign materials for constitutional evaluation and the resilience of democratic systems against acts of constitutional retrogression. Of course, judicial interpretative behaviours and the very state of democracy of a given country are two aspects that are highly influenced by a great number of exogenous and endogenous factors. There indeed may be exceptions to this rule. However, even a brief analysis of African case law, especially regarding topics that are relevant to the overall health of a democratic society, shows that international and foreign law are not just used to strengthen courts’ opinions defending democratic values. They represent the very structure of these judicial reasonings. Up to the point that it would be safe to assume that, had these rulings not used foreign jurisprudence, the decisions would have been substantially different.

These findings are further corroborated by the fact that, with few exceptions, rulings that adopt an international approach to counter instances of democratic decay mostly come from English speaking African countries. Such disproportion could be attributed to the outward-looking constitutional and judicial legacy that these countries inherited from the English constitutional model. In opposition, francophone African states have strictly adhered to the French constitutional model, rarely expanding constitutional and judicial interference beyond the structure of the French fifth republic. This rigidity in constitutional design and judicial interpretation could be one of the reasons why francophone Africa, on average, seems to be performing worse in terms of the quality and strengths of its democratic systems.