Italy in the FRA Fundamental Rights Report 2025: Emerging Issues, Progress, and Persistent Challenges

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Respect for Fundamental Rights in the Electoral Process

- Effectively Protecting Women Victims of Violence

- Implementation and Application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

- Conclusions and Recommendations

Introduction

The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) published its annual Fundamental Rights Report 2025, based on primary research and contributions from its Franet network. This edition reflects on developments in 2024, a year marked by geopolitical upheavals, democratic challenges, and social inequalities. While the report covers all Member States, this article concentrates on Italy’s position in three central spheres: the protection of electoral rights, safeguarding women victims of violence, and the national implementation of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Italy stands at a crossroads between democratic commitments and socio-political pressures. The European elections of 2024 and the domestic debates around disinformation and inclusion highlighted both strengths and vulnerabilities in Italian democracy. At the same time, persistent challenges in combating gender-based violence drew attention to the adequacy of Italian institutions and their alignment with new EU-wide standards. Finally, in the realm of Charter implementation, Italy was singled out for promising practices and projects designed to embed the Charter more deeply in litigation and civil society activism.

Respect for Fundamental Rights in the Electoral Process

Free and fair elections are the backbone of democratic life. FRA stresses that electoral processes must not only guarantee the formal right to vote but also safeguard transparency, inclusiveness, and protection against manipulation. In Italy, the 2024 European elections provided a practical test of these principles.

One of the major themes was the regulation of the online sphere. As campaigns increasingly migrate to digital platforms, Italy faced the challenge of countering disinformation, political advertising opacity, and risks of foreign interference. FRA underlined that governments must balance freedom of expression with the need to secure the integrity of the electoral debate. Italian electoral authorities, alongside EU-wide networks such as the European Cooperation Network on Elections, engaged in risk assessments and public campaigns to enhance media literacy and resilience to online manipulation.

Inclusion remains another crucial element. Italy belongs to a group of Member States with legal quotas requiring gender parity on electoral lists for European elections. The Italian legislation mandates that party lists must include 50% women, placing the country at the forefront of formal gender equality in representation. However, quotas do not always translate into real power, as women may be placed in less electable positions. This raises questions about the gap between legal guarantees and substantive equality.

Beyond gender, accessibility for persons with disabilities and youth engagement continue to be pressing issues. FRA highlights that in many Member States, including Italy, persons with disabilities still face barriers in exercising their electoral rights, whether due to inadequate physical accessibility at polling stations or insufficient provision of information in accessible formats. Italy has made incremental progress, but civil society organisations stress that universal design in electoral participation is still lacking.

The Italian electoral process also intersects with wider debates about political speech. FRA observed cases where journalists and civil society actors faced legal pressures, particularly in politically sensitive contexts. Ensuring that elections remain spaces for free contestation, unhampered by disproportionate legal threats, remains essential for the credibility of democracy in Italy.

Effectively Protecting Women Victims of Violence

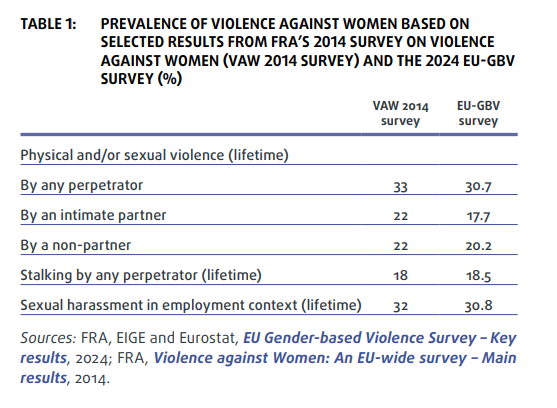

Gender-based violence is one of the most persistent violations of fundamental rights across the EU. FRA’s 2025 report emphasises that around one in three women in Europe have experienced violence, whether at home, in the workplace, or in public spaces. Italy is no exception, and the country has faced intense scrutiny in recent years regarding the adequacy of its response mechanisms.

The newly adopted EU directive on combating violence against women and domestic violence (2024) requires harmonised definitions of offences, minimum standards for victim protection, and effective reporting mechanisms. Italy, already bound by the Istanbul Convention, has begun adapting its legislation accordingly. Notably, in 2024 Italy introduced a new offence of violating restraining orders, expanding protection for women at risk. This development aims to close loopholes where perpetrators repeatedly breached court orders without facing adequate sanctions.

Victims’ rights have also been reinforced. Italian law now grants victims the right to be promptly informed about the release or escape of perpetrators from detention. This addresses a long-standing concern voiced by victim support organisations about gaps in information that left women vulnerable to re-victimisation.

Italy has also been highlighted for innovative digital measures. The Data Protection Authority launched an online reporting tool specifically designed to combat non-consensual dissemination of intimate images (so-called “revenge porn”). Through this platform, victims can notify authorities directly, who then alert the relevant online providers to remove harmful content. This is regarded as a promising practice, showcasing how data protection mechanisms can intersect with violence prevention in the digital sphere.

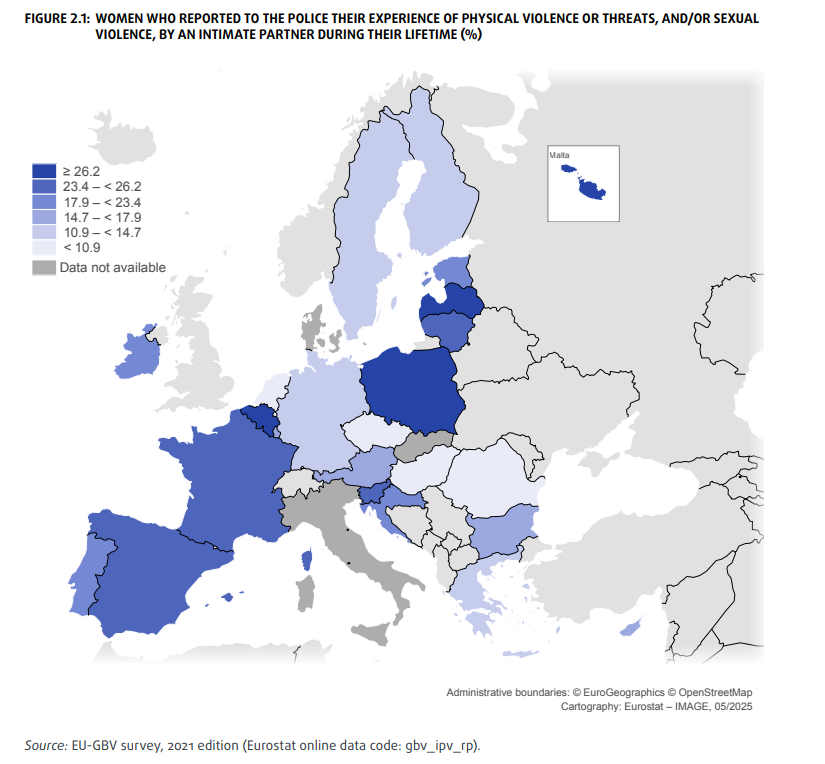

Yet, despite these advances, under-reporting remains a critical problem. According to EU-wide figures, only 13.9% of women who experienced physical or sexual violence reported the incident to the police. Italian NGOs stress that stigma, fear of reprisal, and lack of trust in law enforcement continue to deter many women from seeking help. Moreover, specialised shelters and services are unevenly distributed across the country, with southern regions often lacking adequate facilities.

In X v Greece (No 38588/21), European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) holds that the failure of the investigative and judicial authorities to adequately respond to the allegations of rapeamounts to a violation of the positive obligations of the state under Articles 3 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

In Z. v the Czech Republic (No 37782/21), ECtHR finds a violation of the respondent State’s positive obligations under Articles 3 and 8 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms due to the lack of effective application by Czechia’s national authorities of their criminal law system capable of punishing the non-consensual sexual relations alleged by a vulnerable victim who had not objected to them as they were happening.

Intersectional vulnerabilities compound these issues. Migrant women, Roma women, and women with disabilities face additional barriers in Italy. Effective policies must address these specific vulnerabilities, ensuring that protection systems do not reproduce structural inequalities.

Implementation and Application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

The Charter of Fundamental Rights is the EU’s primary legal instrument enshrining rights of dignity, equality, freedom, and justice. FRA devotes a full chapter of its 2025 report to examining how Member States use and apply the Charter in practice.

In Italy, several initiatives stand out. First, the SCUDI project, funded by the EU’s Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values (CERV) programme, was launched to strengthen strategic litigation capacity around Charter rights. SCUDI focuses particularly on civil society organisations engaged in sea rescue operations, offering training, a legal database, and knowledge-sharing platforms. This initiative illustrates how the Charter can be mobilised in highly contentious areas such as migration and asylum, where Italy plays a frontline role.

National courts in Italy have also engaged with the Charter. Recent constitutional jurisprudence invoked Articles 7 and 20 of the Charter (privacy, family life, and equality before the law) to annul provisions that discriminated between EU citizens and legally resident third-country nationals in the field of judicial cooperation. This reflects an increasing willingness of Italian judges to treat the Charter not as a symbolic instrument but as a directly enforceable legal standard.

Awareness-raising remains a key challenge. FRA emphasises that knowledge of the Charter is still limited among legal practitioners, civil servants, and the general public. To address this, Italy participates in cross-border projects such as FAIR and Stellar, which aim to integrate Charter rights into climate litigation and EU fund management. Moreover, training sessions for lawyers and human rights activists in Italy explicitly emphasise the Charter as a litigation tool, bridging gaps between EU law and national practice.

Nevertheless, Italy continues to face obstacles. The fragmented nature of human rights education means that knowledge of the Charter is concentrated in academic and judicial circles, while local administrations often lack the resources to integrate Charter standards into day-to-day governance. FRA therefore insists on further institutionalisation of Charter focal points within Italy’s regional and municipal structures.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The 2025 FRA report paints a complex picture of Italy’s performance in protecting fundamental rights. On the one hand, Italy demonstrates strong formal commitments: gender quotas in electoral law, criminalisation of restraining order violations, and leadership in digital tools to counter revenge porn. On the other hand, persistent structural problems remain: under-representation of women in political power despite quotas, chronic under-reporting of gender-based violence, and uneven integration of the Charter into everyday governance.

The following recommendations emerge from the analysis:

- Strengthen inclusive electoral participation. Italy should go beyond formal quotas and ensure that women, persons with disabilities, and youth are substantively represented. Electoral authorities must further improve accessibility and tackle subtle practices that marginalise candidates from protected groups.

- Address under-reporting of violence. The Italian government should invest in awareness campaigns, strengthen trust in law enforcement, and expand shelters and services nationwide. Special attention must be given to intersectional vulnerabilities, particularly migrant and Roma women.

- Consolidate Charter implementation. Italy should institutionalise Charter focal points in local administrations, promote consistent judicial training, and embed Charter compliance checks in EU-funded projects. The SCUDI project should be expanded to other sensitive fields beyond migration.

- Leverage digital innovation responsibly. Initiatives such as the Data Protection Authority’s revenge-porn reporting tool should be complemented by broader measures addressing cyberviolence, including mandatory training for police and prosecutors on digital evidence.

- Safeguard press freedom in elections. Italy must ensure that journalists and civil society actors can criticise government rhetoric without fear of disproportionate defamation charges, thereby strengthening the pluralism of electoral debate.

Ultimately, Italy’s trajectory in 2024-2025 illustrates the delicate balance between progress and persistent gaps. Fundamental rights protection cannot be an afterthought; it must guide legislative, judicial, and administrative action at every level. Italy, as a pivotal Member State at the crossroads of migration flows, democratic contestation, and social change, bears a particular responsibility to demonstrate that rights are not just proclaimed but effectively protected in practice.