Little Lives on Hold: The Impact of EU Securitisation Policy Tools on Unaccompanied Children’s Rights at the Greek-Turkish Border

Since the 2015 Refugee Crisis, the EU and its Member States increasingly engaged in securitisation practices at the Greek-Turkish border with the aim to fortify EU borders and keep migrants and refugees at the edge of Europe, without distinguishing among their specific vulnerabilities and needs.

The hope that the humanitarian tragedy that severely hit Europe five years ago could lead to more inclusive and human management of migration based on solidarity among the Member States, crushed against the priority granted in the European Agenda on Migration to the adoption of three mutually reinforcing measures based on the insourcing and outsourcing of EU borders and their militarisation that laid down the foundation for a chain of human rights violations.

Specifically, the creation of the hotspots in the Aegean Islands, the EU-Turkey Deal, and the strengthening of Frontex’s powers gave rise to a border securitisation system built on migrants’ deprivation of their freedom of movement and their fundamental rights that did not exclude even the most vulnerable from the violent border security logic.

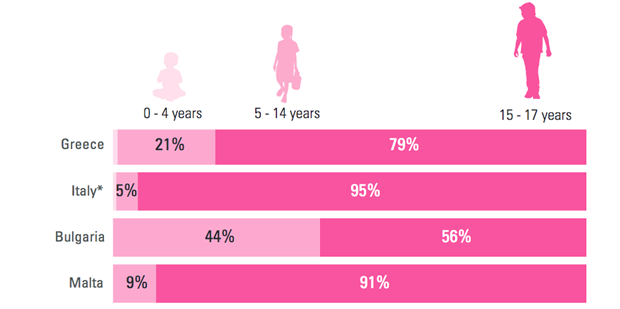

Since 2015, 480,000 migrant and refugee children have transited through Greece to escape armed conflict, persecution, generalised violence, or forced recruitment. Among them, the most vulnerable are unaccompanied children (UAC) who travel without a trustworthy adult and therefore, are more exposed to the risk of being abused or entering the human trafficking business. The majority of UAC arriving in Greece transit through Turkey and they are from Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq. Most of them are between 15 and 17 years old (79%), although the proportion between 5 and 14 years old is significant (21%).

Source: IOM, UNHCR, UNICEF, 2020.

The extreme vulnerability of these subjects and their consistent presence within migration flows raise important questions over their effective protection at the Greek-Turkish border that, as this article will demonstrate, has been increasingly transformed into a transnational open-air prison out of EU’s sight. As a matter of fact, the underlying mechanisms of the three mutually reinforcing strategies that will be discussed below led to the increasing criminalisation of children by transforming them into a potential threat to the security of the Member States that requires exceptional measures of containment.

Setting the stage to secure the Greek-Turkish border: the hotspot approach, the EU-Turkey Deal and the reinforcement of Frontex

The hotspots are one of the first securitisation measures implemented in the framework of the European Agenda on Migration adopted during the Refugee Crisis in which short-term and long-term measures to manage migration flows were outlined.

The hotspots were established as an emergency measure to help frontline Member States in dealing with unexpected migratory pressure. In Greece, five hotspots were opened in the Islands of Lesvos, Chios, Leros, Samos, and Kos. As shown by the image below, they are all situated on the geographical edge of Europe. Although they are the main entry points to Europe and therefore, more exposed to high migratory pressure, their position is also strategically important for the European Union’s securitisation aims.

Source: EU Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) 2016

The hotspots were soon attributed a complementary function to the effective implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement with the aim to identify irregular migrants and refugees as soon as they arrive in Europe and return them to Turkey. Indeed, the EU-Turkey Deal introduced on March 7th, 2016, established that every illegal migrant intercepted in the Eastern Mediterranean or arriving in Greece would be deported to Turkey, after having determined the admissibility of their asylum claims under a fast-track border procedure.

The shift of the hotspot’s aim to the exclusive return of irregular migrants called for increasing detention of asylum seekers in order to make sure that they cannot leave the Greek islands before their application is processed and their status determined, contributing to the transformation of the hotspots into de facto detention centres. The agreement allowed for the transfer of responsibility to Turkish authorities in the interception and apprehension of refugees and migrants before they can reach EU territorial waters.

The third complementary strategy was the increasing militarisation of borderline spaces with the financial and technical support of the EU and in particular, of Frontex. By implementing the Regulation (EU) 2016/1624, Frontex increasingly played a fundamental role in assisting third countries in their function as ‘guardians’ of the EU borders, as well as in the return of irregular migrants although this Agency’s relationship with human rights has been controversial since its inception, mostly due to an accountability deficit.

As it will be described below, the adoption of these border securitisation strategies turned out to be detrimental to UAC’s rights, as they were not counterbalanced by any effective mechanism for their protection.

Unaccompanied children’s lives trapped in the EU securitisation net

Since the 2015 Refugee Crisis, Turkey’s treatment of refugees and migrants started to follow a deteriorating pattern as they increasingly became the object of a restrictive migration policy based on violent pushbacks, detention and unlawful deportation in violation of the principle of non-refoulement. Despite the adoption of these repressive measures that reflected a serious democratic deficit in this country, the EU-Turkey Deal was not suspended. Contrarily, the greater ability of Turkish authorities to detect and contain migrants attempting to reach Europe was financially and militarily supported by the EU.

This new repressive policy, aimed at reducing the increasing migration pressure in this transit country following the sealing off of borders with Europe, did not exclude UAC. Therefore, UAC who accomplish to arrive in Turkey find themselves in this hostile context that makes their journey to Europe more challenging as their rights are increasingly exposed to violations.

In 2016, Tibet and Strasser (2019) documented the transfer of UAC residing in the dedicated shelter of Kadıköy to the refugee camp of Adana, situated just one hour away from the border with Syria (see Figure 1). Soon after the sign of the EU-Turkey Deal, the Ministry of Family and Social Policy gave the order to remove children from State facilities close to the Aegean border to prevent them from crossing it.

The tremendous and painful efforts of these children to reach Europe, that brought them up to the border with Greece, were instantly erased by this political choice that did not take into consideration their ‘best interests’ and the psychological impact that such a harsh decision could have on them. UAC were detained in refugee camps where their freedom of movement was strongly hampered along with their dreams and rights crumbled as soon as they were brought closer to the places from where they were escaping. Samer, a 15-year-old Syrian child, was about to start school and join a football team in Kadıköy but was never given the possibility to realise such aspirations. By referring to the new life in the refugee camp, he claimed that:

“This place was like a barn (ahır). I cried nearly every day about my terrible life. It was humiliating to be there. You know, going from the seaside at Kadıköy to the camp in Adana makes you feel as if you fell off a donkey. I hadn’t realised that we had been living so close to the edge”.

UAC who are able to continue their journey towards Europe and attempt to cross the Turkish border, risk of being detained alongside adults in removal centres or other types in inhumane and degrading conditions, where they have limited access to medical care, legal assistance and information in their own language.

However, the sealing off of borders did not deter UAC from attempting to enter Greece through irregular and unsafe migratory routes, often with the support of human smugglers, increasing the risk of being trafficked as well as exposed to serious abuses. Specifically, Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN) reports that violent pushbacks exercised by Greek authorities often in collaboration with agents of Frontex became systematic in recent years.

UAC, who manage to cross the Aegean Sea, swift from one detention regime to another as the protection of their fundamental rights continues to clash against EU border securitisation policies represented this time by the Greek hotspots. In this sort of limbo at the margin of Europe, the reality on the ground is characterised by serious deficiencies since the commencement of the identification procedures due to the shortage of qualified personnel including doctors, psychologists, and social workers.

This situation gives rise to significant delays and summary practices that lead to unjustifiable violations of children’s rights deeply affecting the course of their lives. Because of the shortage of dedicated accommodation centres in the Aegean Islands and the fact that UAC cannot be transferred to the mainland before their asylum claim has been processed, many of them are placed in ‘protective custody’ for the entire period in which their age is assessed and their application is examined. In practice, UAC are detained in police stations until an accommodation is arranged. Although Greece recently committed itself to end this practice, the lack of accommodation in the hotspots and the dreadful conditions in which children are forced to live represent a matter of serious concern on Europe’s commitment to protecting children’s rights.

Saleh’s words, a 16-year-old boy from Somalia, testify the plight of children who are not able to secure themselves a place where to sleep in the overcrowded accommodation shelters of the hotspots.

“I sleep on the street. I and some other guys my age. There are drunk people at night, and we are very scared. We don’t have a container or a tent. We just live outside, on the street, inside the camp. When we sleep on the ground, at night it’s wet and cold. We have a small carpet like the one Muslims pray on that we sleep on. And I have something to cover myself but it’s very thin, it’s not enough…. I have been told that I am a minor and can’t stay in a tent. I need to be in the place for minors”.

In the hotspots, children are trapped indefinitely in the net of inefficient and endless asylum procedures that step up over their most fundamental rights, but mostly over their dreams and aspirations that are put on hold in the name of Member States’ security.

Life in Moria - The Largest Refugee Camp in Greece | UNICEF

The humanitarian crisis at the Greek-Turkish border: what prospects for UAC?

In March 2020, the Turkish-Greek border was at the centre of a newly announced humanitarian crisis following President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s decision of temporarily opening borders in breach of the EU-Turkey Deal.

In the attempt to reach Greece, thousands of migrants and refugees including children were caught in the spiral of border violence to contain the sudden arrival of a new flow of migrants and refugee which put a strain on the already overwhelmed and dysfunctional reception system in the hotspots. Nonetheless, this migration crisis shed light on the dreadful and inhumane conditions in the Greek Islands.

One of the first measures implemented by the European Commission was to set in place a new voluntary relocation scheme for the transfer of the 1,800 UAC trapped in the Aegean Islands to which the Member States responded by pleading over 2000 places. However, this solution represents a short-term mechanism that, as happened during the 2015 Refugee Crisis, is activated only when an extremely critical situation emerges, ignoring the long-lasting roots of the problem.

The New Pact on Migration and Asylum seems to offer a more concrete solution as it states that unaccompanied children will be excluded from border procedures. However, it remains unclear how this will work in practice. Moreover, the European Commission and Council’s firm efforts to save the EU-Turkey Deal leave unheard the plight of alone children trapped in Turkey or forced to undertake life-threatening journeys.

To conclude, the EU and its Member States must free UAC completely from the border securitisation net in which they have been embedded and give priority to the protection of their vulnerabilities and development of their potentialities, because no little life deserves to be put on hold to protect European borders.