Refugees in the higher education system: overcoming the challenges of inclusion

Table of Contents

Refugees in higher education: context

“We lost our home, which means the familiarity of daily life.

We lost our occupation, which means the confidence that we are of some use in this world.

We lost our language, which means the naturalness of reactions, the simplicity of gestures, the unaffected expression of feelings.”Arendt, We Refugees

As well highlighted by Hannah Arendt, the life of a refugee entails an inevitable journey of pain and deprivation. Everything familiar and everyday disappears, making room for the new, the unknown.

Once arrived in the host country, after navigating through the complicated bureaucracy necessary to formalize their legal status, it's time to try to rebuild one's existence, holding onto memories of the past deep in the soul.

Enrolment into the local educational system represents a fundamental component of the integration process, as well highlighted by UNHCR:

“Education is a basic human right, enshrined in the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child and the 1951 Refugee Convention.

Education protects refugee children and youth from forced recruitment into armed groups, child labour, sexual exploitation and child marriage. Education also strengthens community resilience.

Education empowers by giving refugees the knowledge and skills to live productive, fulfilling and independent lives.

Education enlightens refugees, enabling them to learn about themselves and the world around them while striving to rebuild their lives and communities.” (Source: https://www.unhcr.org/what-we-do/build-better-futures/education)

Yet, despite the tragically constant increase in the number of refugees worldwide (120 million according to the latest UNHCR report), university enrollment numbers are well below the global average: 7%, compared to 42%.

UNHCR, regarding the commitment to ensure the right to higher education, has set the ambitious 15x30 goal: i.e., to reach, globally, 15% of refugees enrolled in universities by 2030.

To achieve the 15% goal, UNHCR has implemented a series of initiatives: in the following paragraphs, the main ones will be described.

Manifesto of the Inclusive University

The Manifesto of the Inclusive University, promoted by UNHCR in 2019, is a formal declaration that saw the participation of 59 Italian universities in 2023. By joining, the universities commit to supporting refugees interested in enrolling in the university, creating a welcoming and inclusive environment, sponsoring scholarships, and encouraging the active participation of refugees in the academic community.

DAFI

Created in 1992, the DAFI (Albert Einstein German Academic Refugee Initiative) scholarship programme provides deserving refugees the opportunity to study at a university.

Thanks to the support of the governments of Germany, Denmark and the Czech Republic, UNHCR and a network of private donors, the programme has enabled more than 18,000 young refugees to obtain their bachelor's degree. The scholarship covers university tuition fees, books, transportation, accommodation, language preparation classes, mentoring and networking opportunities.

Global Compact on Refugees (GCR)

The formulation of the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR) started with the adoption of the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants by the United Nations General Assembly, in September 2016. The Declaration lists a broad array of commitments by Member States, aimed at enhancing mechanisms for the protection of migrants and refugees, as well as supporting host countries. The Declaration requests the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to propose a "Global Compact on Refugees" in his annual report to the General Assembly.

This two-year initiative culminated in December 2018, with the endorsement of the Global Compact on Refugees by the General Assembly. To fully realize the principles of solidarity and international cooperation, the GCR incorporates several instruments, including the Global Refugee Forum (GRF). Held every four years, the Forum gathers UN Member States and other stakeholders to announce tangible commitments and to discuss opportunities, challenges, and strategies for fostering responsibility-sharing.

Education pathways

University corridors facilitate refugees' entry into the host country for study purposes, through collaboration between the Ministry and local NGOs.

The Italian example is leading in Europe, thanks to the UNICORE (University Corridors for Refugees) programme.

Established in 2019 at the University of Bologna, the programme was subsequently extended to other Italian universities in 2020. Thanks to the programme, each adhering university can select refugees and support their enrollment in Italy. UNHCR Italy is responsible for identifying the target countries in Africa and promoting the programme in refugee camps, providing logistical support to those interested, so that they can apply online and participate in remote selection interviews.

The universities participating in UNICORE handle the selection and admission procedures, while UNHCR, with the support of MAECI, manages the logistics related to migration procedures (travel documents, visas, arrival in Italy).

Since the participants are officially refugees in an African country, they enter Italy with a study visa.

For each year of participation, universities are required to sign two protocols: one national, which includes the entire partnership, MAECI, and the associations that coordinate solidarity actions towards the beneficiaries at the national level.

The second formal act that UNHCR asks universities to sign yearly is a local protocol, which commits each university and the associations that will locally support the beneficiaries. This is undoubtedly the programme’s strength: universities are called to create a local network with entities and associations in the area, combining efforts to provide complementary services to ensure the refugees' reception is truly comprehensive. Local associations can, for example, offer Italian language courses, leisure activities, accompaniment for daily life tasks (e.g., visiting the doctor, the police station, the dentist), and provision of equipment such as bicycles, books, and computers.

The University of Padua for Refugees and Students At Risk

The University of Padua joined the UNICORE program in 2020, and since then, under the coordination of UNHCR Italy, it has welcomed two refugees each year from the African countries targeted by the project, supporting their enrollment in a master's degree course at the University.

Moreover, in line with its motto "Universa Universis Patavina Libertas," the University has decided to create ad hoc programmes to support at-risk students, funding them with its internal budget.

Thanks to the UNIPD 4 AFGHANISTAN, UNIPD 4 UKRAINE, and UNIPD 4 MYANMAR projects, young people fleeing at-risk countries have received scholarships to finance their studies at the University of Padua.

In light of the numerous requests for support, in 2023 the University established a working group called “UNIPD 4 People at Risk”, which has since coordinated activities to select every year around 20 refugees and at-risk students and support their enrollment at the University.

Criticalities

While scholarships are undoubtedly a valuable aid, refugees still lack the support that we, as European citizens, often take for granted in our daily lives.

The major criticalities are represented by the linguistic barrier (in non-English speaking countries such as Italy, a good level of the local language is required, for everyday life outside the university walls), everyday expenses such as clothing, medicines, transports, and, probably most importantly, loneliness. This is an aspect that tends to be underestimated: during holidays and free time, when services and offices close and people return to their families, refugees are often left alone. Luckily, especially after the pandemic, the importance of taking care of mental health is increasingly recognised, and consequently psychological support is now offered in most universities for free. Another crucial issue is the access to the job market, a moment which of course is challenging for every student, but refugees cannot rely on family support and consequently they must navigate the job market alone and quickly. Moreover, in this phase, linguistic skills become fundamental again.

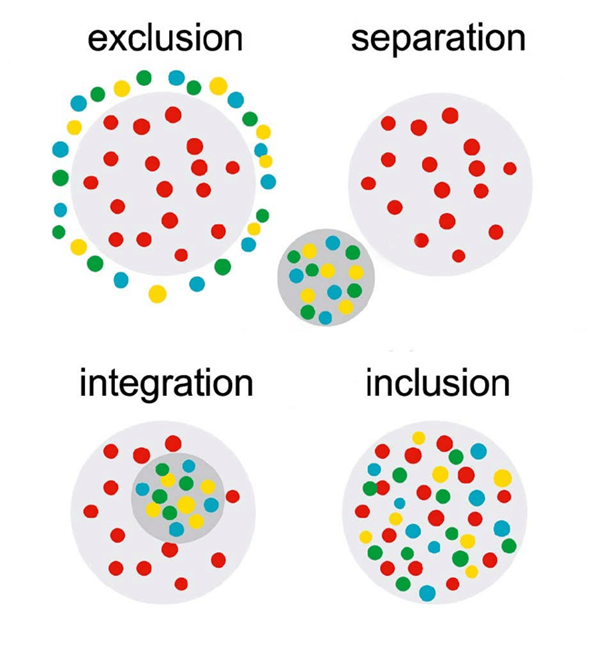

This highlights the significant difference between integration and inclusion: while universities promote integration through access and scholarship payments, true inclusion is a much more complex process that necessitates constant collaboration with other local entities to meet all student needs.

Figure “Differentiating exclusion, separation, integration and inclusion”, from Ridley-Duff, Rory & Southcombe, Cliff & Schmidtchen, Roger & Pataki, Veronika & Wren, David & Arnold-Schaarschmidt, Martin & Vukovıć, Sonja & Klercq, Jumbo & Trzecınskı, Stefanıe & Oparaocha, Karin & Károly, Judıt. (2018). Methodology for Creating a FairShares Lab. 10.13140/RG.2.2.11461.50404.

Obviously, this requires a much heavier workload than simply paying scholarships, which is why the number of selected students should remain low, to adequately support them.

A positive example, in addition to the previously mentioned UNICORE programme, is offered by the University of Trento, which annually selects five refugees who are legally residing in Italy and offers them a comprehensive support package: not only tuition waivers, meals, and accommodation, but also dedicated tutoring, local accompaniment, and, if necessary, a pre-enrollment foundation year.

Conclusions

For years, UNHCR has been implementing concrete actions to improve the inclusion of refugees into the university environment.

Why should universities undertake such demanding activities?

Universities, as places of culture, knowledge dissemination, and cultural defense, on one hand, and as public institutions rooted in the community, on the other, have a duty to improve the very societies they inhabit. Culture elevates: and if one intends to elevate young minds and spirits, the best way to do so is by example, and in this case, the example consists of concretely trying to address the injustices of our time.

Many universities in Italy and abroad have created welcoming and supporting programmes for refugees, asylum seekers and students at risk: the Author will investigate possible successful models, such as the UNICORE programme and the ones created in Ireland and Belgium, with the final aim of drafting a national inclusion plan for refugees in Italian universities.