Cambodia, EBA and the Bloody Sugar Industry: the impact of international trade on local communities’ food security

In our globalised world, trade has almost no limits and what we find on our table (most of the times!) comes from far-away exotic places. The global demand influences what is produced worldwide, and has an impact on human rights, especially in the Least Developed Countries (LDCs). The shift from traditional harvests to cash-crops threats LDCs’ food security and access to natural resources. In the worst cases, this global request lead to the phenomenon of land grabbing, which enslaves entire communities.

The Sugar Industry in Cambodia is a clear evidence of how international trade can be a threat rather than a spur for development. This sector was encouraged by an international economic agreement, Everything But Arms (EBA). EBA was drafted by the European Council at the beginning of 2000s. The purpose was to eradicate poverty in the 47 LDCs listed by the UN through trade, by granting preferential access to the European market, to all products, except weapons: the LDCs’ integration in the international community would have helped their development. There are no quantitative restrictions and no limits, but the agreement is non-contractual, which means that it depends just on EU’s decisions. Actually, the lack of guarantee clauses risks generating a negative impact on local communities’ subsistence and on the environment, as declared by D. Pred, cofounder of Inclusive Development International.

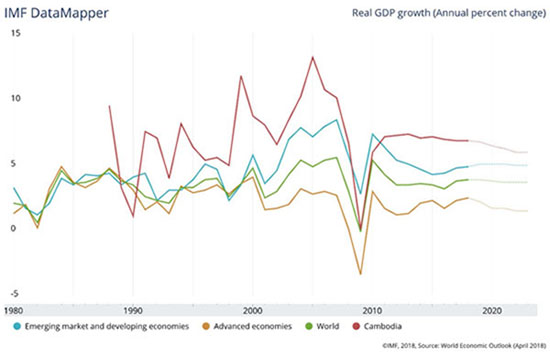

Following the EBA, in Cambodia, exports to the EU have recorded a 227% growth between 2011 and 2016. According to Jean-Francois Cautain, ex EU ambassador in the Kingdom, “Cambodia is a prime example of the EBA scheme’s power as an engine of growth”. Cambodia, together with Bangladesh, is the biggest partner of the EU, under the EBA, according to the 2018 Report on the Generalised Preferential Schemes. Exports to the EU reached 2.32 billion in 2012 (42% of total Cambodian exports that year), and 5 billion in 2017. This led to a great economic growth: according to the International Monetary Fund, annual average GDP-growth for the period 2001–2010 was 7.7%, making Cambodia one of the world's top ten countries with the highest annual average GDP-growth, and numerous jobs have been created.

However, new wealth was not evenly distributed and human rights violations have been huge and severe. The “development” has costed land expropriation to approximately 400,000 Cambodians, since 2003.

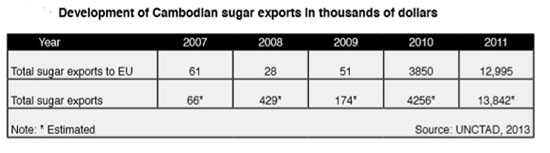

Considering sugar, Cambodia used to import it, in order to face the national demand. With EBA, companies from Thailand, China and Taiwan, in partnership with local companies, have started to lease huge plots of land to produce sugar and export it to the EU. Exports raised more and more, till 2013. The main EU partner was Tate&Lyle, a huge British multinational agribusiness, specialised in sugar refining.

By analysing these numbers, it would seem that Cambodia’s development was great. But let’s look deeper. The Cambodian government started to grant Economic Land Concessions (ELCs), regulated by law with the intent to spur development by using lands to produce exportable products (Check ELCs on LICADHO Website).

Regarding sugar, ELCs were granted to companies such as Ve Wong Corporation (Taiwan), KSL Group (Thailand), Rui Feng (China), Lan Feng (China), Heng You (China) and Heng Nong (China), Mitr Phol (Thailand); they all cooperate with local companies (such as Koh Kong Plantation, Koh Kong Sugar Industry, Phnom Penh Sugar, Kampong Speu Sugar), owned by the prime minister, Hun Sen, and the Cambodian senator, Ly Yong Phat. According to Open Development Cambodia “nearly 12% of the country’s land has been granted to investors under terms of ELCs”. Lack of transparency and disrespect for laws emerged: ELCs not only violated local communities’ needs and human rights, but also exceeded size restrictions and avoided constraints for consultation, proper compensation, and social and environmental impact assessment.

These lands were not free but inhabited by farmers. During the Khmer Rouge regime (1975-1979), every form of private property was eliminated, and all lands were considered as state property. After this period, land property wasn’t immediately re-established, it took many years, laws and regulations. Nowadays, land rights remain one of the most contentious issues in Cambodia and people still don’t own proper property on their lands: this put them in a condition of extreme precariousness, and they can easily become victims of expropriation. Forced eviction is considered illegal both by local laws and international conventions, however through ELCs, this is what happened. Used to live on their agricultural activities, peasants found themselves in extreme poverty. Actually, prior to ELCs, the situation was stable: they weren’t rich, but at least they could produce enough food for their families and their living standards were acceptable; after ELCs they lost their only source of subsistence. The paradox is that ELCs, aimed at improving the economy and related living standards, actually undermined food security for locals. As a consequence of greater food insecurity, other aspects of daily life were threatened, such as health, security, education. Lastly, only few peasants were hired by the companies, which feared “internal strikes”, and even so, at inhuman working conditions. Many families decided to migrate.

Furthermore, ELCs and the Bloody Sugar Industry have affected also the environment: more than ¼ of Cambodian forests have been cut off and numerous water sources have been polluted. Even if farmers had their lands back, they would not be able to use them.

In 2006, the first ELC related to sugar was granted in Koh Kong. Since then, other concessions were granted in Kampong Speu, Oddar Meanchey, Preah Vihear, Svay Rieng, Battambang. The rush has heavily increased till 2013.

In 2012, local and international NGOs started to raise awareness about this issue, with the so-called Cambodian Clean Sugar Campaign, which actually cooled down the situation (sugar exports to the EU decreased dramatically, plummeting by nearly 95%, in 2013), but didn’t solve land issues. The main actors are Equitable Cambodia, Community Legal Education Center, Licadho and Adhoc. The scope was not to stop EBA nor trade, but to introduce guarantee clauses for rural peasants. As a response to the higher and higher protests, an attempting solution was adopted by the government, through a moratorium (2012), which suspended the granting of new ELCs and declared intentions to review the existing ones. However, the situation didn’t improve, and farmers are still protesting today. Protests have always been stopped with violence by the government, or by limiting civil society space, and thus, by violating farmers’ freedom of expression and assembly.

The EU has almost ever been aware of what was happening, thanks to reports and complaints delivered by protesters and local NGOs, but it has never taken the situation seriously. Things started to change in July 2018, when the EU organized a fact-finding mission, intended to evaluate the situation regarding human rights and land issue. Indeed, according to art 19 of Generalised Preferential Schemes, preferences are suspended “in the event of serious and systematic violation of the core 15 UN and ILO conventions”. EU’s concerns regarding democracy and human rights in the Kingdom started when the country’s main opposition party, Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP), was dissolved and its leader, Kem Sokha, arrested (2017). Moreover, the denial of political rights, restrictions to civil society and trade unions, lands issue, labour issues and denial of freedom of association and collective bargaining, all pushed EU’ fears. After meetings at the highest level, last October, measures for the suspension became more and more concrete, with the Commission’s proposal. The proposal was approved by Member States at the end of January 2019. In February 11th, 2019, the EU declared its decision for a temporary suspension of the EBA in the Kingdom. The suspension-process will take 18 months: 6 of intense monitoring and engagement with Cambodian authorities, in order to find new opportunities to cooperate, and to gather data; 6 to produce a report regarding changes; and eventually other 6 months, to implement the definitive withdrawal (scope, duration and which preferences). However, as declared by the EU Commissioner for Trade, Cecilia Malmstrom, the move is “neither a final decision nor the end of the process […] but the clock is officially ticking”.

The government has expressed its disagreement with the European decision, declaring it “unfair”. Indeed, since EU concerns emerged, some improvements have been undertaken: release of 19 politicians and activists; strengthening of the civil society space and promotion of a more transparent government; attention to labour rights and land issues; amendment of art 45 of the Law on Political Parties.

The impact of this process will be “catastrophic” for the economy, as stated by Sophal Ear, who is Cambodian-USA associate professor of diplomacy and world affairs at Occidental College in Los Angeles. The withdrawal will cost Cambodia approximately $676 million. Two possible patterns have been identified: on one side, the government will grant democratic concessions, to meet European standards and access again to its market; on the other, the break up with the EU will push the Kingdom into the “Chinese orbit”, generating even further risks for human rights. Plus, EBA’s withdrawal will jeopardize any possible future long-term efforts to build local capacities for safeguarding democracy. Lastly, many jobs will be cut off and unemployment will spread around the country.

To conclude, the intention of the EU, through EBA, was noble, but guarantee clauses are always needed to make human rights respected. Economic interests govern our system; thus, a greater attention should be put in order to avoid breaches. Moreover, we are all to be considered responsible every time we go grocery shopping: we must be aware of the products we buy and their origins.