An Ethnic Lunch as a Multitude of Acts of International Solidarity

Table of Contents

- The International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

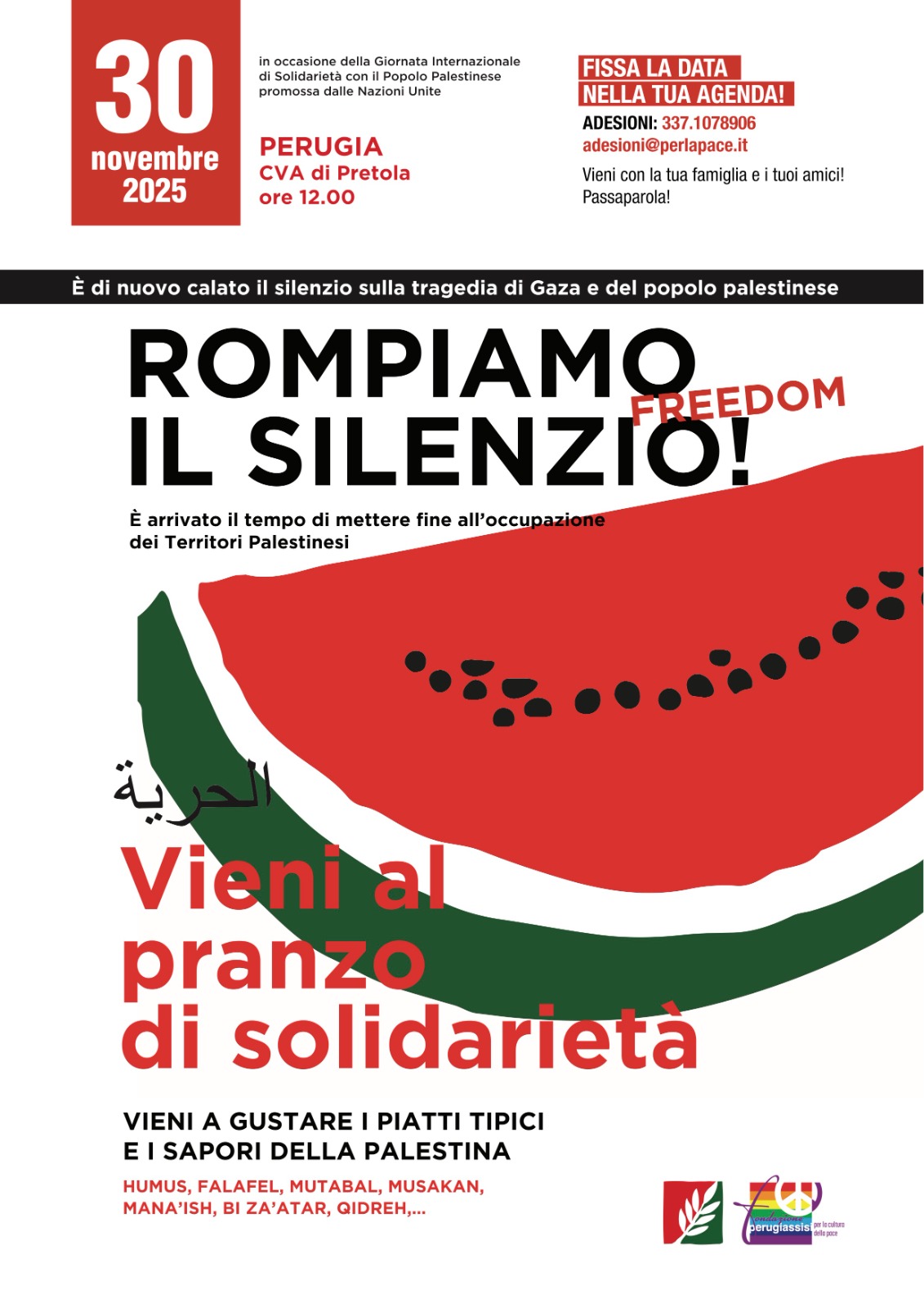

- 30 November: a lunch of solidarity

- A shared kitchen in Perugia

- Cultural diplomacy and food diplomacy

- Conclusions

The International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Since 1977, the United Nations has designated 29 November as the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People (see the UN webpage dedicated to the Day). The date is far from symbolic: on 29 November 1947, UN Resolution 181 was adopted, intended to initiate the process leading to the establishment of two States for two peoples. Each year, events are held at United Nations headquarters to mark this occasion, with particular emphasis on the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination. This right has also been affirmed by the International Court of Justice, the principal judicial organ of the United Nations responsible for the peaceful settlement of disputes. In its Advisory Opinion on the “Israeli Wall” of 9 July 2004, the Court stated in paragraph 118 that “as regards the principle of the right of peoples to self-determination, the Court observes that the existence of a ‘Palestinian people’ is no longer in issue”.

The Palestinian people existed before the British mandate and before the partition of 1948. Today, however, commemorations held within the framework of the United Nations—where representatives of the very States that failed to prevent the ongoing genocide take part—have lost part of their moral force. The situation in Gaza starkly highlights the ambiguity of those who continue to support Israel’s actions while simultaneously participating in solidarity events for the Palestinian people. Nevertheless, global civil society continues to play its part, expressing solidarity each year on this date through appeals, conferences, screenings, and solidarity lunches. It is essential that, on this day, both the rights of the Palestinian people and the obligations imposed on Israel by numerous UN resolutions are recalled, including the duty to withdraw from the occupied Palestinian territories, as the acquisition of territory by force is illegal, to respect the 1967 borders, and to recognise Palestinian refugees’ right of return.

30 November: a Lunch of Solidarity

This year, the PerugiAssisi Foundation for the Culture of Peace chose to mark the Day with a solidarity lunch pursuing specific objectives. First and foremost, it called for freedom for the Palestinian people in the exercise of their inalienable right to self-determination, enshrined not only in the United Nations Charter but also in the identical Article 1 of the two 1966 International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (see the appeal for 29 November). Today, after more than two years of destruction and death in Gaza, this right is even more endangered by the peace plan approved by the UN Security Council at the initiative of the President of the United States. As already noted by the Human Rights Centre, this plan represents a plan of war rather than one of peace (see the article of 25 November).

Secondly, solidarity must take concrete form. The lunch, therefore, aimed to raise funds to support a family from the Gaza parish, now refugees in Italy: a four-year-old girl, a seven-year-old boy, a young mother seriously injured by bombing, and an equally young father who, together, are attempting to rebuild their lives. After enduring horrors difficult to imagine, this family managed to escape the Strip and reach Perugia. The funds raised on 30 November will help them settle in the Umbrian capital and painstakingly reconstruct a sense of normality that had been absent for over two years.

More than 270 residents of Perugia and across Umbria responded to the initiative, gathering on Sunday, 30 November in Pretola to share traditional Palestinian dishes and to stand together with those who have lost everything. Associations and local institutions also took part, including the Association for Pretola APS; Giovani Musulmani d’Italia (Perugia branch); the Province of Perugia; the Municipality of Perugia; the Upper Tiber Valley Peace Coordination; ANPI Marsciano; Articolo 21; AVIS Perugia; Banca Etica Perugia; Still I Rise Umbria; the Casa dei Popoli of Foligno, among many others. Considerable collective effort went into organising the venue, spaces, kitchen, and services required for such a large gathering. Ultimately, all participants were able to enjoy Palestinian food and drink thanks to the remarkable work carried out in a shared kitchen by people from diverse backgrounds (see article on the lunch).

A Shared Kitchen in Perugia

In the kitchen, under the guidance of Randa—a Palestinian woman coordinating the work of the National Network of Schools of Peace from Perugia—men and women from the Association for Pretola and members of the local Muslim community worked side by side. They prepared a menu of traditional dishes, because a country’s culture is conveyed through what is shared at the table. Thus, chickpea hummus and labneh with olives appeared alongside pizzas topped with Palestinian ingredients, resting on a base unmistakably influenced by Italian culinary culture—perhaps shaped by the hands of Perugians blending their skills with Randa’s expertise. The bread, khobez, was baked by a Lebanese bakery in Rome; rice dishes with aubergines, chickpeas, and saffron brought diners back to Palestine; and sweets with tea concluded a meal that felt like a journey through the culture of what is currently one of the most threatened regions in the world.

A recently published book by Meltemi offers a similar journey through images of Palestinian culinary culture. It was unsurprising to encounter at the lunch dishes described in this volume, which is neither a guide nor a recipe book, but rather a concrete act of protection of Palestinian flavours and traditions. Entitled Pop Palestine, written jointly by Italian food writer Silvia Chiarantini and Palestinian food writer, interpreter, and lecturer Fidaa I. A. Abuhamdiya, the book serves as a practical manual for safeguarding traditional Palestinian cuisine while simultaneously narrowing cultural distances that often appear insurmountable, despite being separated by only a narrow stretch of sea.

Cultural Diplomacy and Food Diplomacy

In that kitchen, and later around those tables, distances were shortened, prompting reflection grounded in international relations theory. The analysis begins with classical definitions of cultural diplomacy and one of its branches, culinary diplomacy. Cultural diplomacy today is employed in international relations as an instrument of soft power, moving beyond even Cummings’ (2003) widely cited definition of it as the “exchange of ideas, information, art, language and other aspects of culture among nations and their peoples to foster mutual understanding and, consequently, advance foreign policy goals”. Food diplomacy represents a clear sub-category, defined as “the strategic use of a nation’s cuisine and culinary heritage to cultivate intercultural understanding, build relationships, and create a favourable national image” (Cabral et al., 2024). As Luša and Jakešević (2017) observe, food is “a universally accessible medium that transcends linguistic and political barriers, making it an ideal instrument for the projection of soft power”.

While States may use cultural diplomacy to exert influence over ‘others’, often without generating positive outcomes for the populations subjected to it, civil society organisations—particularly non-governmental ones—can employ cultural diplomacy to foster genuine peacebuilding processes and societies enriched rather than threatened by difference. Unlike national cultural institutes, NGOs do not represent governmental lines; their credibility is built through practice, action, and networks grounded in trust and genuine reciprocity.

In this sense, culinary diplomacy is not limited to displays of excellence at embassy gala dinners or to humanitarian aid used as leverage. A solidarity lunch can also be understood as an act of food diplomacy. Community-centred meals harness the universal power of food to create localised, empathetic impact, shifting attention from national culinary prestige to values of compassion, hospitality, and shared humanity. Such events function as forms of “micro-diplomacy”, providing tangible and immediate responses to human needs while strengthening community bonds. By involving participants in the preparation and sharing of food, they encourage dialogue and mutual respect, contributing to conflict mitigation and social cohesion at the local level (Luša & Jakešević, 2017).

Conclusions

In short, practices of solidarity and community sharing that seek to include segments of society at risk of marginalisation can also be described as forms of food diplomacy, fostering a sense of social justice that many fear has been lost.

Seeing 270 people—of different cultures and life stories—eating together, sharing the same food and the same objective of contributing, was undoubtedly the greatest success of the solidarity lunch held on 30 November. Many such meals have been organised in recent months, all driven by the same idea and the same ultimate goal: to promote knowledge of Palestinian culture, to protect it from the assaults and risks posed by the ongoing violence and genocide in Gaza, and ultimately to build a more just and peaceful world in which human rights are sometimes defended simply by breaking the same (Arabic) bread at the table.